Missing Links : U.S. Archeologist Seeks Proof of His Theory That Roads Connected Distant Maya Cities, Perhaps Into One Nation

- Share via

ALUKMUL, Mexico — William J. “Willie” Folan is looking for a 2,000-year-old road. Several of them.

An American archeologist who works for the local Universidad Autonoma de Campeche, Folan has been excavating this remote jungle site of a major Maya city since 1982.

Discovered in 1931 but largely ignored until Folan initiated his work, the Calukmul site is an archeological treasure trove--to date, it has yielded 114 engraved upright stone slabs, called stelae, more than any other Maya site. With the advances in the last decade in reading Maya carved pictographs known as glyphs, much can be learned from the carvings on these monuments.

Folan’s discoveries, including a surrounding wall to protect the city from invading armies, a major tomb with an intact skeleton named “Long-Lipped Jawbone” and jade and pearl ornaments have already shown that Calukmul was a major center with a population of 50,000 and at least 6,250 structures, rivaling and warring with the early Maya city of Tikal in what is now Guatemala.

He is now searching for evidence to support his long-held theory that Maya sacbes (sac meaning “white” and be meaning “road” and pronounced SOCK-BAY) not only provided concourse within urban areas but also stretched to distant cities, linking states or regions.

Proving the theory he has shared with Joyce Marcus of the University of Michigan would mean that political states developed in the Western Hemisphere far earlier than previously thought.

It could also mean the Mayas lived not in isolated cities but in an organized, connected nation, the forerunner of modern society.

Sacbes, 6-foot-high causeways built with stone fill to keep pedestrians above the area’s many marshes and swamps in the wet season, have been found as much as 20 kilometers long in carefully studied Maya sites such as Uxmal and Chichen Itza. But Folan believes he will find roads connecting Calukmul to such distant centers as Mexico’s Coba, about 300 kilometers to the northeast, and even more certainly to the Guatemalan sites of El Mirador, 43 kilometers to the south, and Nakbe, another 12 kilometers beyond.

Richard D. Hansen, who has excavated El Mirador and Nakbe since 1989 for UCLA’s Regional Archaeological Investigation of the North Peten, Guatemala, project, is skeptical but hopeful that Folan can prove that such long roads exist.

Hansen has confirmed that Maya development in the two areas took place centuries before previously thought. His findings have shown that El Mirador was built about 200 BC and Nakbe as early as 630 BC, which would make it the first Maya city.

Archeologists have believed that Mayas drifted north to Calukmul after the demise of the Guatemalan centers.

But the existence of connecting roads could show that the cities coexisted. Folan believes his research could move back Calukmul’s known Classic Maya roots in about AD 600 to the Preclassic period a few hundred years BC.

Although skeptical about the roads, Hansen is as hopeful as Folan about proving that connections of some type linked the ancient cities into a broader society.

“I would love it if he is right,” Hansen said during a rare encounter with Folan early this year when the UCLA scientist led the first large group of visitors, organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History and San Francisco’s Academy of Science, into Calukmul.

“The reason I have doubts,” Hansen said, “is that we have NASA photos of the sacbe system radiating out of El Mirador, and they just go so far and stop. They don’t seem to connect to other cities.”

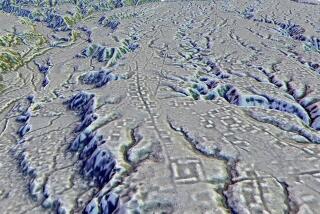

Folan began his investigation 12 years ago with remote sensing using Landsat satellite imagery in which variations in vegetation and elevation indicated a pattern of lines radiating from Calukmul. At first he suspected that the lines were canals, but later decided they were roads--the Maya-built sacbes. Unlike Hansen’s two-dimensional aerial photos, the remote sensing technique can, by detecting chlorophyll content and other differences, distinguish land from water and natural vegetation from man-made objects such as the missing roads.

The Campeche archeologist, Marcus and W. Frank Miller of Mississippi State University recently published a progress report in the Cambridge Archaeological Journal on their search for the roads. Folan said he soon will publish a map of the road system that has taken him seven years to develop.

He is now physically slashing through the jungle in an attempt to scrape out the actual roads.

“We want to be damned sure they do what we think they do,” he said.

Both Folan and Hansen work deep in the jungle, Folan in Mexico’s Calukmul Biosphere Reserve (which he helped establish in 1989) and Hansen in Guatemala’s adjoining Maya Biosphere Reserve. They share concerns about dangers such as falling trees and snakebites.

Folan, 63, an American educated at the University of the Americas in Puebla, Mexico, has worked at Maya sites in Mexico since 1954, and earlier mapped the little-excavated Coba. His efforts are primarily funded by the Mexican government, which according to Hansen and other U.S. scientists views archeology more as a tourist draw than a precise science. Lack of money is a constant worry.

Hansen, 43, an Idaho potato farmer educated at Brigham Young University and UCLA, additionally worries about looting and, working cautiously with the Guatemalan government, is careful to study and preserve his finds within Guatemala. But he is somewhat better funded--with UCLA and American foundations behind him--and consequently can use NASA resources and other state-of-the-art technology.

Both men, however, will try any scientific methods they can to link ancient cities and expand knowledge of the complex and sophisticated Maya civilization.

Hansen is considering mirrors or torches, for instance.

From atop Calukmul’s massive 50-meter-high Structure II, a pyramid that Folan excavated only two years ago, Hansen gazed at a tiny peak on the horizon 43 kilometers away--the tallest pyramid at El Mirador, where he planned to continue his work this spring. He and Folan’s wife, researcher Linda Folan, discussed scheduling attempts to communicate between the pyramids at their respective sites.

If a torch at night or shiny surface in daytime could be seen from one site to the other, it could show how Mayas may have communicated with each other 15 or 20 centuries ago.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.