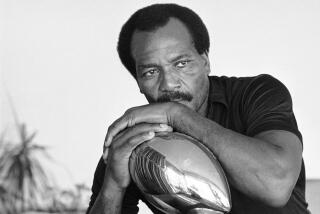

Brown Made a World of Difference in Commerce

- Share via

“I’ve been with him on trips to China and India. I’ve seen him tell government officials point-blank: ‘Here’s an American company offering you the best possible deal. If they don’t get the contract, it’s because the playing field isn’t level.’ ”

Thus did a U.S. businessman recall Ron Brown, the secretary of Commerce who died last week in a plane crash in Croatia.

Brown’s toughness was recalled not only as an epitaph but as an object lesson for what the next Commerce secretary and any future holder of the office must do to be effective in a complex and competitive world.

Brown made a difference because he understood that government officials must fight to get U.S. companies a fair share of projects and markets in foreign lands. Those increasingly are the source of jobs and investments in the United States. And it’s important that Americans feel the global system is working fairly.

Official figures stating that exports directly support 13 million U.S. workers or account for one-third of U.S. economic growth understate the reality. International business today is a matrix of contacts in which work overseas begets work at home and vice versa.

Yet until Brown’s time and that of Secretary of State Warren Christopher, the U.S. government often adopted a stance of indifference to business abroad. Either it didn’t fight or didn’t have to. During 45 years of the Cold War, a lot of business came to American firms simply because the U.S. armed forces were protecting other countries.

But that advantage receded in recent years. Not only did military prowess offer less leverage, but the world’s economies began a historic shift.

Newly industrializing countries became the growth markets, especially as they installed electricity and telephone systems and built factories and office buildings. The countries of Asia, which already account for more U.S. trade than Western Europe, will spend $2 trillion on infrastructure before 2000; Latin America will spend $500 billion.

In such economies--particularly on matters of infrastructure--governments make decisions. And U.S. companies depend more than ever on backing from their own government. “The commercial diplomacy begun by Ron Brown must be accelerated. We cannot afford to backslide in this changing world,” says Jeffrey Garten, dean of Yale School of Management, who served with Brown as Undersecretary of Commerce from 1993 to late 1995.

Many of the companies represented on Brown’s fateful flight last week are in engineering and construction of infrastructure projects--Parsons, Bechtel, Foster Wheeler, ABB, Harza Engineering.

Those companies are good examples of the value of services--really of brainpower as a valuable commodity with tremendous ripple effects in the world economy. The engineering contractor can specify suppliers and call forth support systems from computer analysis to transportation and communications.

The big contractors do half or more of their business overseas, competing against government-backed firms from other countries.

To be sure, the focus is on business, not nationalism. Joseph Jacobs, founder of Jacobs Engineering in Pasadena, recalls receiving help from the British embassy in Amman, Jordan--after being cold-shouldered by the U.S. embassy--on a project in which Jacobs had a British partner.

Such indifference has changed, thanks to Brown and Christopher. “Every U.S. embassy now has skilled people who really want to help,” says Edward Muller, president of Edison Mission Energy, which builds power plants overseas.

Support work in Washington is better, too, since Brown created a war room at the Commerce Department to track competition for worldwide projects--including the widespread bribes that characterize the shadier side of global competition. U.S. companies are prohibited by law from paying bribes, and that can sometimes be a disadvantage.

Brown’s counter to bribery was typical. He’d do his homework, have his facts and confront the other government’s officials. He learned early about business and confronting the unexpected. His parents owned Harlem’s famed Hotel Theresa, where Fidel Castro’s aides lit open fires in the rooms to cook chickens during an early 1960s visit to the United Nations.

“He had tremendous energy,” Muller said. Brown’s successor will have to be energetic, too, and tenacious.

Paradoxically, given the demands of the times, there continues to be support in Congress for eliminating the Commerce Department as a budget-cutting move and because Brown’s ideas of helping U.S. companies run counter to beliefs of some members of Congress that government shouldn’t help business. The controversy is part of an underlying division of opinion as to whether the global economy benefits or threatens U.S. living standards.

But the threat to Commerce ignores the facts of a rapidly changing world--and fears of the global economy are beside the point. A new study by the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs predicts that trade between China and Japan alone will account for 28% of world commerce in 2015, compared with 13% today.

That’s not a threat, it’s a reality to be dealt with. “Our fastest-growing customers and competitors are the same people,” Yale’s Garten explains. “The Brazils and Chinas and Indias compete now in low- and medium-technology areas. Ultimately they’ll compete and exchange high-tech goods and services with us.

“I’m confident we can do well if we concentrate on educating and helping our work force at home and on commercial diplomacy abroad.”

Ron Brown understood that competition is fine with Americans as long as they’re convinced we’re getting a fair shake in world trade. That’s what he worked for. And that’s what all his successors, at Commerce and other departments, will have to understand and work for from now on.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.