Message From Afar: Maybe It’s a Lively Universe

- Share via

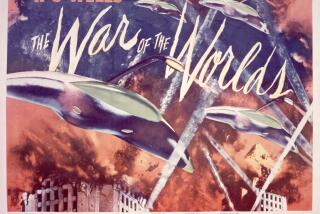

In the 19th century the West was the last great American frontier, a perilous terrain that was opening a land of dreams, California. In the 20th century, a new vision began to beckon, outer space, and our neighboring planet Mars became our favorite symbol of this new frontier. We gazed at the Red Planet, read novels about its inhabitants and aimed our Tom Corbett ray guns at movie screens showing “The War of the Worlds” and “Invaders from Mars.” In the great observatories, astronomers took a more scientific, but nonetheless fascinated, approach to worlds beyond our own.

Today, some of those Martian fans can be found at NASA and Pasadena’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. In 1976, they got their first chance to guide a U.S. probe, Viking 1, to the surface of Mars, and they wanted more.

However, when Viking 1 sent back pictures of a dusty, dry, freezing surface as desolate as the moon, our collective interest in Mars began to seem driven less by science than fantasy. We had, after all, been partly inspired by science fiction writers misled by a map of Mars crafted by Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli in 1877. Schiaparelli had referred to canali, meaning channels or grooves, but this was mistranslated as “canals,” which may have fostered the belief of many that Martians had dug aqueducts.

But if a carefully controlled and widely respected study to be published in the Aug. 16 issue of Science magazine proves to be correct, then our dreams about the Red Planet may not have been so fantastical after all. At a NASA press conference Wednesday, researchers explained how they had examined a softball-sized rock that crashed into the icy Allan Hills of Antarctica after having been chipped off the Martian surface about 15 million years ago.

Within the rock’s minuscule fissures, the researchers found particles similar to those produced by bacteria on earth. The nature and “spatial association” of these particles offer “evidence for primitive life on early Mars,” said Richard Zare, one of the paper’s chief researchers and an internationally respected chemist.

“If this discovery is confirmed,” President Clinton said Wednesday, “it will surely be one of the most stunning insights into our universe that science has ever uncovered.” Clinton has directed Vice President Al Gore to convene a bipartisan space summit at the White House later this year on the future of the space program and on how to pursue questions raised by the Martian meteorite.

Long before the President’s announcement, two Mars missions had been set: The Mars Global Surveyor, scheduled to be launched in November, will make a complete map of the planet. The Mars Pathfinder, to blast off in December, will arrive on the surface of the Red Planet on Independence Day of 1997, one year after those creepy aliens attacked Earth in a recent blockbuster film. Both missions will be coordinated from JPL in our backyard.

Undoubtedly, scientists are going to use the inconclusiveness of the Science study to lobby for more ambitious Martian projects. Some of the proposed missions seem only marginally useful and, well, astronomically expensive. British biologist James Lovelock, for instance, wants to turn Mars into a habitable planet by “terraforming it,” giving it an atmosphere by freeing the carbon dioxide purportedly fixed in its crust.

Other proposed missions seem more promising. Some researchers, for instance, think that meteor fragments like the one found in Antarctica act like seeds, sprinkling DNA, a blueprint for life, around the solar system. By retrieving DNA samples from Mars, we may one day be able to trace the evolution of this master molecule, they argue.

Of course, what Mars has told us most about is ourselves.

The planet has mirrored our fears of alien invaders, as in Orson Welles’ classic radio broadcast of “War of the Worlds.” And it has also mirrored our dreams after World War II, as in the many 1950s yarns about ancient, silent Martians eking out the last precious water from their melting poles and glancing enviously at that blue water planet between them and the sun.

A short story by Ray Bradbury best symbolizes Mars’ place in our imagination. An Earthly colonist of Mars takes his daughter down to a canal to show her a Martian. She is told to look into the water, and in it she sees her own reflection.