H.G. Wells’ alien-invasion novel is night-before-Halloween scary. But it’s a lot more too

- Share via

The invasion began 125 years ago, got reinforcements on the night before Halloween in 1938 and still occupies cultural territory in the 21st century.

In 1898, H.G. Wells published “The War of the Worlds” in which Martians — “intellects vast and cool and unsympathetic” — mount an attack on Earth, specifically against England and the towns and country Wells knew intimately.

An eyewitness narrates the arrival of strange cylinders, the curious and curiously mild reaction of bystanders, the horrifying egress of bloodthirsty Martians, their heat rays, their poisonous “black smoke” and their weird, walking tripods that leave devastation and a red weed in their wake. The plant is a symbol of humanity’s coming defeat. We’re saved only because the Martians are infected by terrestrial germs.

Classic Hollywood: The PBS documentary ‘War of the Worlds’ marks the 75th anniversary of Orson Welles’ panic-inducing broadcast.

The novel was a roaring, if ominous, success. Wells almost single-handedly invented the motif of the extraterrestrial invasion, and the prospect of alien armies from space went on to conquer popular culture, from feature films to radio plays, opera, comic books, video games and TV, including the creepy, currently streaming series “Invasion.”

Today, worries about an attack from the sky reach beyond fiction. No less than physicist Stephen Hawking has warned against humans advertising our presence in the cosmos because our messages could alert hostile beings. The U.S. government now takes seriously reports of UFOs or, in current parlance, “unidentified anomalous phenomena.” (In a twist, some say that if sightings of fast-moving, physics-defying objects are real, the best case would be that they are extraterrestrial. If not, it means other governments have technology America does not.)

Since “The War of the Worlds,” we’ve taken extraterrestrial hostility for granted. We didn’t always.

NASA’s new instruction to the U.S. public regarding unidentified anomalous phenomena boils down to a version of the popular security slogan: “If you see something, say something.”

Wells wrote at the tail end of what was called the “plurality of worlds” debate. Once Galileo showed that Earth’s moon was a physical place and that Jupiter had multiple moons, a theological and philosophical question emerged: Would God waste other worlds by leaving them empty of life? The answer then was probably not. Instead, the expectation was that they’d be populated by beings more intelligent and more rational than Earthlings. There were utopias in the sky! Secular angels!

Wells turned that assumption on its head and used it to convey harsh truths about colonialism and to illustrate fears of war. “The War of the Worlds” explicitly referenced how European colonists waged a near-genocidal campaign against the Indigenous inhabitants of Tasmania. The story also played off worries that a belligerent Germany, even in the late 19th century, could invade England.

‘War of the Worlds’ is sci-fi at its best -- riveting and relevant.

Fifty years later, on Oct. 30, 1938, actor and director Orson Welles transplanted the novel to New Jersey, scripting a radio play that sounded like a real newscast and that evoked another ominous time. For Americans aware of Europe’s fascist stirrings, the Welles/Wells invasion hit home. Despite announcements that the broadcast was a dramatization, many listeners mistook it as real. A 1940 study suggested that a million people panicked, though historians still aren’t sure how widespread the fear was.

According to Los Angeles Times reporter Susan King, writing in 2013, “Listeners called into Chicago newspapers in a panic during the broadcast, while in San Francisco people fretted that the Martians were heading West. And in New Jersey, National Guardsmen were calling their armories to find out if they needed to report.”

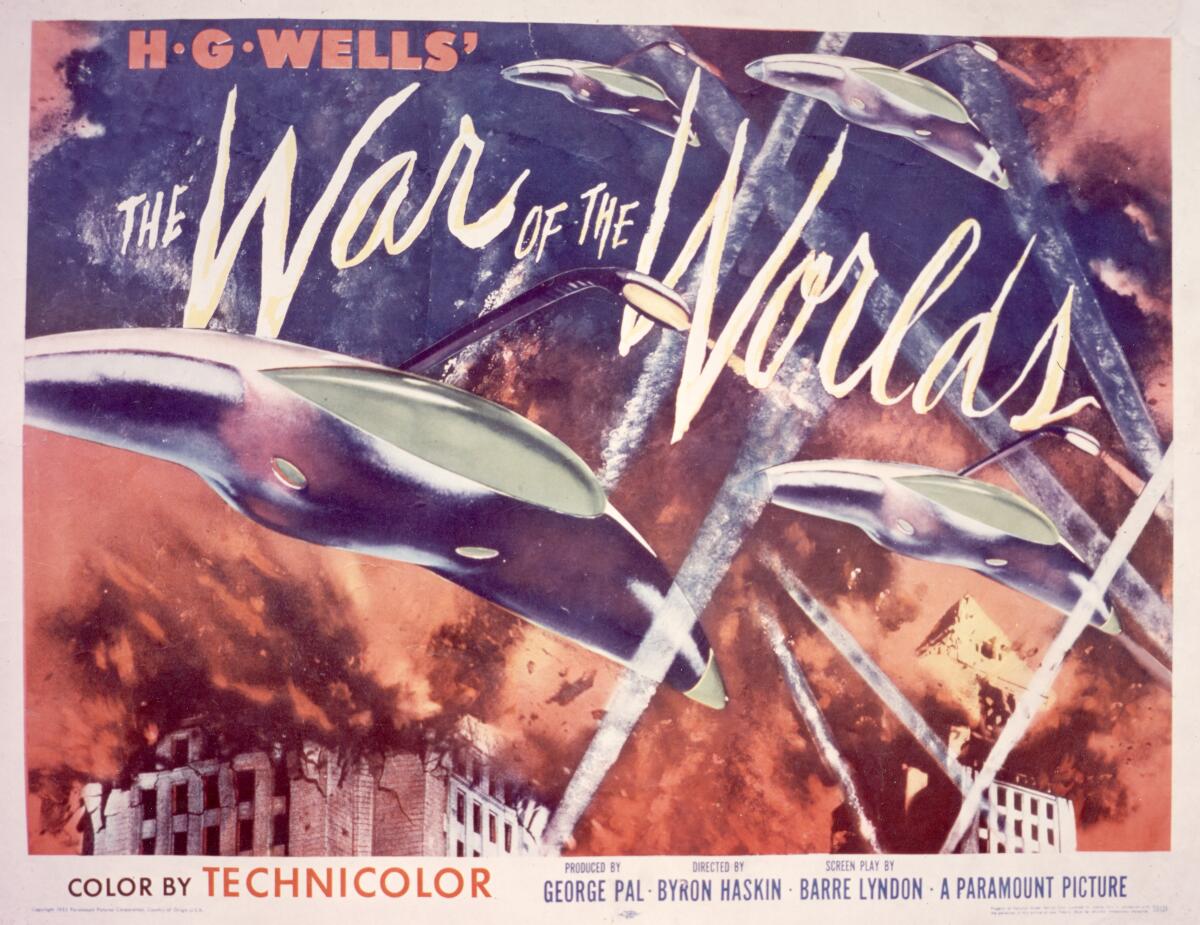

California and Los Angeles became the setting for the 1953 George Pal movie version. As the Martians begin to emerge from a large meteorite, one character asks, “What are we going to say to them?” Another offers, tentatively, “Welcome to California.” It does not go well.

It would be too easy, as scholars have pointed out, to reduce “The War of the Worlds” and its various versions to an entertaining horror or simply a tale about aggression and human fragility. The novel and its adaptations contain so much more.

At the end of “The War of the Worlds,” Wells’ narrator considers our capacity to meet the future. It requires, he suggests, what we still need: a sober, unbiased view of science, history and psychology. Wells was also a socialist. The book can be read as a plea for making common cause, as his biographer David C. Smith suggests. In this time of real invasions, terrorist attacks, occupations and counteroffensives, that plea is especially poignant.

To this can now be added a complementary, if more subtle, view. It’s a perspective Wells would have appreciated. Beneath anxiety over extraterrestrial invasion and the need for common cause should be the acknowledgment that we are the aliens and the aliens are us.

The calcium in our bones came from stars. The oxygen, carbon and iron — all from stars that died, exploded and sent their elements outward. All of us, everywhere, at all times carry the unfathomably distant and ancient stars in us. The stars connect us all.

Fully embracing that could make us a bit more humble, a bit more open to one another. Instead of diminishing ourselves with fear and anger, we could live up to the universal, star-begotten legacy we’ve inherited: our kinship with, well, everything.

Christopher Cokinos’ natural history of the moon is forthcoming in 2024. He lives in Utah.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.