Robbers of the Sea Without the...

- Share via

On the Caribbean coast of Panama, at the head of a snug oval harbor guarded on each side by the ruins of two forts, lies what is left of the ancient city of Portobelo: a church with a famous “Black Christ,” some old cannons, a few sheds on which in the heavy sultry air watchful vultures perch.

Portobelo was once the terminus to which pack animals carried gold and silver from Peru and Bolivia for shipment to Spain. In 1688 the British buccaneer Henry Morgan fell upon the forts from the landward side, forced the town to surrender and made off with great treasure. “The capture . . . was one of the most successful amphibious operations of the 17th century,” writes David Cordingly in “Under the Black Flag.”

The episode, with the captures of Panama City and Maracaibo, won Morgan fortune, a knighthood and fame among the British people, who were engaged in the long off-again, on-again struggle with Spain.

These tales and many others about pirates are engagingly told by Cordingly, a deft writer who served on the staff of the splendid National Maritime Museum at Greenwich, England. His book has excellent maps and illustrations.

Cordingly touches on pirates through history and around the world.

But he focuses on “the great age” of piracy in the Western World. It began in the 1650s and ended “abruptly” in about 1725 when naval patrols “drove them from their lairs and mass hangings eliminated many of their leaders.”

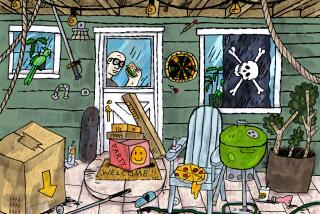

This is the age from which springs the concept of the romance of piracy, a notion contrary to most of reality of the thing itself. Pirates were robbers on the sea, given to extraordinary acts of cruelty. But in the popular mind, though not wholly without foundation, they have somehow come to represent a life of mysterious adventure and a certain individual freedom.

The great merit of Cordingly’s book is that he weaves together the story of what the pirates actually were with the narrative of how we came to see them as we do.

It is a tale of the power of imaginative literature to re-create the past.

“The effect of ‘Treasure Island’ on our perception of pirates cannot be overestimated,” Cordingly writes of Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1883 novel. “Stevenson linked pirates forever with maps, black schooners, tropical islands and one-legged seamen with parrots on their shoulders.”

In the early 19th century it was Lord Byron who contributed to the pirate craze; his epic poem, “The Corsair,” sold 10,000 copies on the first day of publication in 1814.

Closer to our own time there was Gilbert and Sullivan’s endearing “The Pirates of Penzance,” of which Cordingly writes that “its cast of hearty and good-natured fellows have contributed to the illusion that pirates were really misunderstood ruffians who never meant to harm anyone.”

Cordingly writes an amusing account of the creation of J. M. Barrie’s “Peter Pan,” in which appeared the second-most-famous pirate character of all, the improbable villain Captain Hook. “Over the years a Peter Pan industry has grown up,” he writes. With many Christmas holiday performances of the play in America and Britain, with the Disney movie and Steven Spielberg’s “Hook,” it is little wonder many children first learn about pirates through seeing some version of the Peter Pan story.

“Pirates,” a coffee-table-sized book, makes an excellent companion volume with its rich use of color photographs and prints of pirate objects, ship models, old paintings and the illustrations of Howard Pyle and Frank Schoonover.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.