Law Students Go Through Motions--and More

- Share via

FULLERTON — Forced out of the comfort of climate-controlled libraries and classrooms, some Orange County law students are rolling up their sleeves and sweating over motions, witnesses, police and autopsy reports.

At the Western State University College of Law in Fullerton, third-year law students are working side-by-side with attorneys with the county offices of the district attorney and the public defender. The internship program is designed to give aspiring lawyers a working knowledge of the criminal law system. And as legal students learn the ropes, overtaxed attorneys are getting much-appreciated help.

“We perceive that we are part of a trend,” said Dennis Honabach, dean of the law school. “And that is to make sure that our students are exposed to practical skills, both in the classroom and in live, client experiences.”

Professor David Biggs, who spearheaded the program, said that while other schools may also offer internships, few work so closely with district attorneys and public defenders. The joint effort offers not only regular evaluation of the students’ performance, but an opportunity for them to scrutinize their real-world criminal law experiences in a weekly classroom setting. Since the program’s inception in January, seven students have been working with deputy district attorneys and seven with assistant public defenders. Biggs expects enrollment in the program to more than double by the fall.

Though much of their time is spent researching, students also have opportunities to write and argue motions in court, prepare files and attend jury trials. Students are even treated to tours of jail facilities and the coroner’s office--complete with an autopsy.

“I’m very squeamish and thought it would really affect me but it didn’t,” said 33-year-old student Alicia Burnham. Instead, “we learned how the coroner fits into the picture of the criminal justice system.”

One of the greatest benefits of the program, some said, is its ability to introduce the human element of law to students.

“They’re seeing live people, victims who have been harmed by the loss of property or assault, and they’re seeing defendants who are going to get punished, if convicted, through the criminal justice system,” said Rick King, who heads the homicide division of the district attorney’s office. “It’s a more realistic perspective about the system.”

Burnham’s wake-up call came when she first dealt with real police reports of child molesters, batterers and murderers.

“These are real people, that was a real body, a real person, the police talked to the family members, and that person sitting in jail is waiting for his fate to be decided,” she said. “It’s surreal.”

The free legal assistance is a relief for Orange County’s financially strained and understaffed courts, Biggs said. “The [court] system is almost on the brink of breaking down and it needs all the help it can get. These students are not the answer, but they are some of the solution.”

The students are required to clock at least 150 hours of public service, but most put in more than 200. Meeting the minimum requirement is never a problem, they said.

“I can’t imagine doing the bare minimum,” Burnham said. “The nature of the work makes you want to excel at it. I definitely feel like I could be there a lot more hours and probably have tons more work to do.”

Unfazed by the long hours, students view the internship as an opportunity to hone skills outside the classroom.

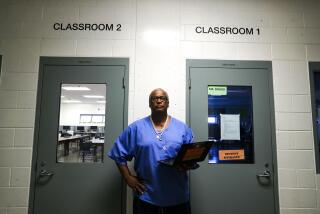

“I’m still struggling with organizing research,” said Bettye Strother. “Sometimes I’ll pull a lot of cases and I won’t quite know where to put them. It’s not something I’ve never done, it’s about getting more experience.”

WSU’s internship program is part of a larger group of curriculum changes the school is making in its quest for American Bar Assn. accreditation. By scaling back requirements, incorporating more practical skills-oriented classes and offering a greater diversity of classes, Honabach--who arrived at WSU nine months ago from the District of Columbia Law School--hopes students are better able to specialize their curriculum to match their career goals.

Tom Havlena, head of the Superior Court division of the public defender’s office, said the program attracts some of the best students who are nearing the end of their law school experiences.

“It is the bridge between the halls of academia and a real-world law practice,” he said, “with the bar exam in between.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.