Seeking New Treatments for Cystitis

- Share via

Without looking at the next sentence, name the second most frequent form of illness among women, next to the common cold. The answer is urinary tract infection.

And if most of the public isn’t aware of the prevalence of this growing problem, doctors and researchers certainly are.

Every year, an estimated 1.5 million American women are hospitalized with such infections, commonly called UTIs, and another 6 to 7 million visit their doctors for treatment. Although the problem responds well to antibiotics, physicians are uncovering increasing numbers of drug-resistant strains of the bacterium that causes the problem.

Many women, furthermore, suffer troublesome recurrent infections, and the very young and the elderly are especially susceptible to severe illness caused by the infections.

But help may be on the way. Scientists are testing two new vaccines to prevent UTIs, one in humans and one in primates. The former, which will probably provide protection for only a few months to a year, could be available by 1999.

The latter, which is in an earlier stage of development but is expected to provide a more lasting protection, will not see general use until early in the next millennium. But if it is successful, it may provide a completely new way to attack a broad variety of bacterial infections.

The vaccine being studied in primates “is a major breakthrough in vaccine technology, with a lot of potential applications,” said Dr. Anthony Schaeffer, a urologist at Northwestern University Medical School in Evanston, Ill.

UTIs, also commonly known as cystitis, are characterized by frequent, urgent and painful urination, fever, and blood or pus in the urine. They are a classic case of a simple bacterium being in the wrong place at the right time.

Our guts are normally overrun with a common, well-known bacteria called Escherichia coli. In its proper place, E. coli is harmless, perhaps even beneficial. But drop it into the normally sterile bladder and it quickly raises havoc.

*

For women and UTIs, anatomy is destiny. The close proximity of the openings of the bladder and the vagina to the rectum allows fecal bacteria to creep across the perineum--the tissue between the openings--and into places where it shouldn’t be. Sexual activity speeds up the process, which is why, in an earlier, more innocent age, the disease was often called honeymoon cystitis. Young girls frequently developed it shortly after they were married.

Cystitis is not a sexually transmitted disease, however, because the microorganism that causes it does not come from the sex partner, but rather from the victim’s own body. It is what scientists call a “sexually associated” disease.

Untreated, UTIs can produce kidney failure and death. “Blond bombshell” Jean Harlow died from kidney damage caused by cystitis in the era before antibiotics were available to treat it. Today, physicians commonly use Gantrisin, Macrodantin or oral penicillin over a five-day period to eradicate it. A new drug called Monurol provides one-dose treatment.

“But antibiotic resistance is becoming more and more of a problem,” says microbiologist Scott J. Hultgren of the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. “So it’s becoming increasingly important to develop novel ways to fight infection. Vaccine development is one avenue to take.”

One vaccine against UTIs already exists and has been marketed in Europe since the late 1980s. Called Urovac, it is composed of several different strains of killed E. coli and provides protection for several months. But toxins released from the dead bacteria frequently provoke painful inflammation around the injection site, as well as other side effects.

Dr. David T. Uehling and his colleagues at the University of Wisconsin in Madison are attempting to circumvent such reactions by putting the same basic components found in the Urovac vaccine into vaginal suppositories. The slow release from the suppositories spreads the killed bacteria throughout the entire vagina rather than concentrating it at one site, thereby minimizing side effects.

In preliminary trials on 91 women reported in the June Journal of Urology, they found the vaccine at least partially effective. Women in the trial who were prone to recurrent UTIs took an average of five weeks longer than unvaccinated women to develop an infection after vaccination, and none reported any side effects.

*

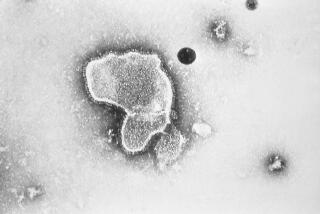

In the new vaccine being studied in primates, Hultgren and his colleagues have focused on the long fiberlike appendages, called pili, by which E. coli attaches itself to cells in the vagina and bladder. Their goal is to prevent these pili from attaching to the two organs.

Other researchers have previously tried to achieve this by immunizing women with genetically engineered pili produced in the laboratory, but they found that vaccination with pili from one strain of bacterium provided no protection against other strains. The pili were also hard to produce.

Hultgren and immunologist Solomon Langermann of MedImmune Inc. in Gaithersberg, Md., concentrated on a particular part of the pili, a protein on the end--called adhesin--that anchors to receptors in bladder and vaginal tissue. Unlike the variable pili, they found, the adhesin molecule is identical in 49 of 52 E. coli strains they tested, suggesting that antibodies against it would protect against most strains of E. coli.

They were able to grow large quantities of adhesin in the laboratory and use it to vaccinate mice. “The idea is very attractive,” Hultgren said, “because such a vaccine would give bacteria a double whammy--antibodies against the protein would both block attachment and mark bacteria for destruction by the immune system.”

Mice vaccinated with adhesin were able to repel all subsequent injections with E. coli for 7 months, the longest time studied, suggesting that the approach is very effective. Dr. Staffan Normark of the Karolinska Institutet in Sweden is now testing the vaccine in primates. If those trials are successful, the team could begin human trials in 1998, Langermann said.

Success with cystitis could bode well for a number of other diseases, including otitis media, pneumonia, meningitis and gonorrhea. All are caused by bacteria with pilus-associated adhesins, and the technology used for the cystitis vaccine should work equally well with them, Hultgren said.

The new knowledge the team has gained about how the pili are assembled by bacteria could also lead to the development of antibiotics to block their production. “These would represent a whole new class of antibiotics--one of the first in 20 to 30 years,” he concluded.

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

A Vaccine for Cystitis

E.coli attach to a receptor on the lining of the bladder by means of a protein, called adhesin, on the ends of the spidery filaments called pili. A new vaccine produces antibodies against adhesin, which bind to both adhesin molecules and the receptors, blocking infection.

Unvaccinated

Vaccinated

Source: Washington University School of Medicine