From Out of the Blue, a Cotton-Pickin’ Great Fertilizer

- Share via

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — Al Romero may have a cure for them lowdown, lint-pickin’ blue goo blues.

It was getting him down, realizing that about 50 cubic yards of blue sludge a week comes out in the wash at International Garment Processors Inc., an El Paso, Texas, company that launders blue denim duds with tags such as Levi Strauss & Co., Wrangler, Polo and Gap.

“That was one of my problems. I hated to see the stuff go to a landfill. I knew there was some application that could benefit,” says Romero, the company’s director of environmental health and safety.

At $300 to $600 for 20 cubic yards dumped in the landfill, all that blue sludge can be pricey. Then Romero heard about research going on at New Mexico State University in Las Cruces, just up the road from El Paso.

Dana Porter started the yearlong research in April 1995 when she was an agricultural engineer and assistant professor at New Mexico State.

Along with David Dotson, then a graduate student at New Mexico State, she studied the benefits of applying the sludge, which is mostly damp blue cotton lint, directly to land or composting the stuff.

“I decided to do something that was real instead of research-oriented with no goal in sight,” Dotson says. “If I did something like this, it could benefit somebody somehow.”

Dotson says Romero asked him about it in November, “out of the blue,” as it were.

Porter, now an extension specialist in agricultural engineering at the West Virginia University Cooperative Extension Service in Morgantown, looked into applying the sludge directly on farmland.

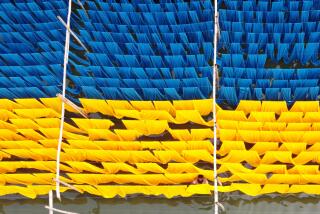

“It looks very blue at first. Then it kind of bleaches out a little bit in the sun. It starts to take on a more gray look,” she says.

Her research showed yields of beans and cotton increased 50% to 60% when the sludge was used, says Dotson, who now works with a consulting engineering company in Alamogordo.

Dotson’s research initially involved direct application on the land and evolved into composting the sludge. He used some sludge on fairly sterile mine tailings and planted native grasses. Yields increased 1,000%, he says.

“I planted my frontyard with it with grass seed like you buy at Wal-Mart and it’s the best yard on the street,” Dotson says.

The secret: the sludge--loaded with cotton fiber--holds and absorbs moisture in the soil, then degrades, adding nutrients, he says.

Robert Flynn, a New Mexico State assistant professor of agronomy, has been studying since October the idea of mixing the sludge with manure from dairy farms--abundant in the Roswell area--to make a compost with a high fertilizer value.

“We’re adjusting the mix ratio to get a real nice organic, usable product for either field application or for greenhouses or for landscaping purposes,” he says.

The compost is a potential moneymaker as long as the sludge, manure and any other components--such as sawdust from sawmills--are found close to one another.

Romero says recycling the blue goo could save IGP $60,000 to $70,000 a year in disposal costs and perhaps earn $200,000 to $400,000 annually from composted material.

“Preliminary studies found that this blue sludge has a capacity to hold water that’s 500% better than the soil that’s down here,” Romero says. The sludge may even help his company turn nearly 900 acres of desert land that it owns into an oasis.

IGP now uses its recycled water to irrigate 70 to 100 acres of alfalfa on company land, he says. “They have about nine cuttings per year and they sell it to a dairy down the road,” Romero says.

In the next six to 12 months, the company will plant another 60 acres of alfalfa, using the blue stuff as fertilizer.