Oldest Man-Made Structure in N. America Found

- Share via

Long before the Egyptians began building pyramids, North Americans were erecting massive earthworks that reflected sophisticated leadership skills and the ability to warehouse the large quantities of food necessary to sustain their construction efforts, new archeological discoveries show.

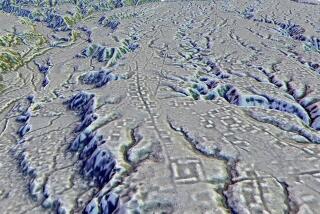

A team of researchers reports today the discovery of the oldest reliably dated human-made structure in North America, a 5,400-year-old earthen mound at Watson Brake, La., that is almost 2,000 years older than nearby sites.

The circular mound, as tall as a two-story house, forms an enclosure nearly 300 yards in diameter, but its purpose is not yet clear.

The discovery of this and other mounds in Louisiana and Florida suggests that the earliest Americans, long thought to be simple hunter-gatherers who roamed the countryside in small, mobile bands, were actually a fairly sedentary people capable of organizing and executing large civil engineering projects, the team reports in the journal Science.

The discovery “totally changes our picture of what happened in the past,” says archeologist Vincas Steponaitis of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“We are reassessing our whole theory of what we thought about the evolution of societies,” said National Park Service archeologist Mike Russo of the Southeastern Archeological Center in Tallahassee, Fla. “We once thought society was very slow to develop in North America. In fact, there were numerous societies here capable of monumental architecture much earlier than we had ever expected.”

And what is becoming clear, he added, is that some of these early groups had a relatively comfortable existence, with ample supplies of food and enough time on their hands to undertake massive public works projects.

Such societies had to have a rich biological niche to support relatively large populations without the benefit of agriculture, he said, but they also had to have “social conventions that would allow them to do something innovative, like build mounds. They were a little less conservative than some of the other societies around them.”

Although archeologists have often tended to ignore them and the public is often unaware of their existence, thousands of human-made mounds dot the East and Midwest. Two to three millennia old and shaped like massive serpents, giant cones or square platforms, these mounds in some cases have been shown to have served as ceremonial centers, slaughterhouses or residential sites.

More often, however, their purposes have remained mysterious, lost in the mist of civilizations that had not yet invented writing or pictorial displays.

Still older mounds are being found in Louisiana and Florida, where the rich mixture of local wildlife and aquatic life from bays and rivers was capable of supporting larger populations. One of the oldest well-documented such sites is Poverty Point in northeastern Louisiana, about 100 miles from the new find at Watson Brake.

Poverty Point, named for a nearby plantation, was built about 3,500 years ago by a people who clearly had prospered from trading. Archeologists studying it have unearthed flint from what is now Ohio, soapstone from northern Alabama and Georgia, copper from Michigan, crystal quartz from Arkansas and chert from Missouri.

That community seemed “unusually precocious,” Russo said, apparently springing up in full bloom without any historical predecessors. The much older Watson Brake discovery, he said, “explains Poverty Point.” Although researchers have not yet found any direct links between the two sites, it seems clear that Watson Brake is a more primitive example of the planning that later characterized Poverty Point.

The shape of the mound was hidden by a dense forest of pine until the 1980s, when some of the trees were clear-cut. A recreational archeologist named Reca Jones then recognized the overall outlines of the circular mound.

Eventually, she and others attracted the interest of Joe W. Saunders of Northeast Louisiana University, a state archeologist. Visiting Watson Brake, he observed an unusual weathering pattern in the soil of the mound, indicating not only that it was human-made but also that it was unusually old.

Using both conventional radiocarbon dating and newly developed soil dating techniques, his team concluded that construction of Watson Brake began about 5,400 years ago and concluded 400 years later.

“There have been similar dates for other mounds in the area, but they have always been ambiguous,” Saunders said. “One date would be old, one would be much younger. Ours are all old.”

The dating is very convincing, said archeologist Jon Gibson of the University of Southwestern Louisiana. “There’s just no question about it.”

Excavating selected segments of the mound, his team, which includes specialists from across the country, found an ancient garbage dump, or midden, containing bones of deer, rabbits, squirrels, dogs and other wildlife, as well as skeletons of assorted local fish and shells of snails and mollusks from the prehistoric Arkansas River. No human bones were found.

The midden contained seeds from three wild plants that would later be domesticated in the Southeast. Although the Watson Brake seeds showed no signs of domestication, said botanist Kristin Gremillion of Ohio State University, they could have been gathered and eaten for their starch.

Excavations revealed traces of primitive toolmaking facilities and six unusual spearheads called Evans points, with two notches on each side of the blade. These are quite different from the more sophisticated Epps and Motley projectile points found at Poverty Point.

They also found drills that were probably used to make beads, but only one complete bead and a few fragments were discovered. In contrast to Poverty Point, all of the material found was local in origin.

“It was pretty dull digging, to tell the truth,” Saunders said.

By far most of the artifacts were fire-cracked rocks used for cooking. Because pottery was not yet invented, the Watson Brake residents would heat these rocks in their fires, then immerse them in water to boil the water or splash water on them to produce steam for cooking.

“We have a quarter-ton of fire-cracked rocks in the lab,” Saunders said.

The most unusual objects were small cubes, and other shapes, of fire-hardened clay, about two inches in size. “We have no idea what these were for,” Saunders said.

The biggest mystery of all, however, is why the structures were built in the first place. They were clearly built atop sites where the people had lived before construction began, and the builders lived on them while they were under construction.

The northern part of the circle, moreover, was built in three separate segments, one on top of another, at different times, he said. The southern segment, in contrast, was built in one continuous effort.

And apparently no one ever lived in the area enclosed by the mounds. Sifting of the soil through fine screens has revealed no traces of the debris that would be there if humans had used the area.