Biannual Chlamydia Screenings Urged

- Share via

While chlamydia is the most frequently reported sexually transmitted disease in the nation, most people who are infected don’t know it, making screening all the more important. The federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that all sexually active women under 20--who are at greatest risk for the infection--get tested for chlamydia during annual examinations. But new research suggests that, in many cases, once a year is not enough.

In a 33-month Johns Hopkins University study of more than 3,200 girls ages 12-19, researchers found high rates of infection--one in three patients tested positive for chlamydia at least once during the study period. The teenagers were visiting family-planning, STD and school-based clinics in Baltimore.

The study, published last week in the Journal of the American Medical Assn. and conducted from 1994 to 1996, was composed almost entirely of African Americans in low-income communities, which are both risk factors for chlamydia infection.

Previous studies in other areas and with more diverse populations have shown lower prevalence rates ranging from 5% to 15%.

In addition to the high infection rates in the area, researchers found that half the people who first tested negative were infected about seven months later, and half who first tested positive were reinfected six months later. Most showed no symptoms. Overall, chlamydia goes undetected in half of infected men and 75% of infected women. Getting screened twice a year would catch more infections earlier, said researchers.

Researchers say that money spent now to treat chlamydia can head off higher costs from medical complications down the road. Up to 40% of women with untreated chlamydia develop pelvic inflammatory disease, a leading cause of infertility and potentially fatal tubal pregnancy. Detected early, chlamydia can be easily treated with antibiotics.

*

Yet the recommendations may not apply to all cities, caution health providers and officials. “Not every area in the country is the same as inner-city Baltimore,” said Dr. Helene Gayle, director of the National Center for HIV, STD and TB Prevention at the CDC. “It’s not reasonable that in every locality people need to go every six months.”

“You can’t develop a policy out of data on one small subgroup of the population,” said Dr. Mary-Ann Shafer, associate director of adolescent medicine at UC San Francisco.

Nevertheless, health care providers shouldn’t assume annual tests are sufficient until they know how prevalent the rate is in their area, said Dr. Gale Burstein, lead researcher and a specialist in adolescent medicine at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Hygiene.

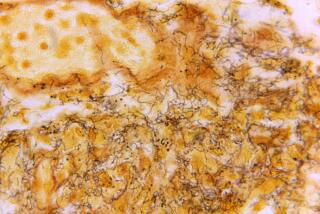

Yet part of the problem with getting accurate figures is that states have only recently begun regular screening and reporting for chlamydia infections. More than 477,000 cases of chlamydia were reported in the U.S. in 1996, the most recent figures available, but officials from the CDC say many more go undiagnosed. As many as 4 million may be infected, with half occurring in females 15 to 19 years old. Girls are at greater risk because the bacterium that causes chlamydia targets the columnar cells that are more prominent in their outer cervix lining. As women mature, those columnar cells are replaced by flatter cells that are less prone to infection.

Older women also tend to seek out longer relationships, notes Dr. Donald Orr, professor of pediatrics at Indiana University School of Medicine and coauthor of an editorial accompanying the study. They thus have fewer sexual partners and fewer chances to be exposed to chlamydia.

Getting teenagers, particularly males, to visit clinics more frequently may be a challenge, said Gayle. “Because adolescence is a relatively healthy period of time, the idea of getting routine maintenance health care is not on their radar screen,” she said.

Some teenagers may also be put off by the prospect of getting a pelvic exam, which was necessary for chlamydia screenings in the past. But new, sensitive urine-based tests are now available and can be easily administered in school clinics. “That’s the advantage of this,” said coauthor Dr. Thomas Quinn, professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. “Kids don’t mind urine tests. And we can bring [the test] to them.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.