Czech Kids Stand and Deliver

- Share via

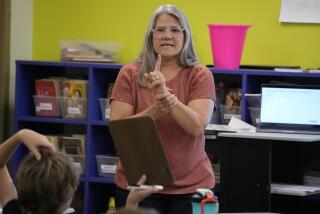

PRAGUE, Czech Republic — It’s 10:45 on a Wednesday morning, and Miss Gabrielova’s first-grade math pupils have been bent over their sums for nearly an hour.

Squint your eyes, and you might be in an American classroom from the early 1960s. The kids are sitting at old-fashioned double desks, neatly arranged in rows. There are no friendly little tables, no free-form seating, no cozy rug to sit on. No one is sent flitting from one small-group project to another. There isn’t a PC to be seen.

Instead, the 24 children have been putting cardboard numbers in order, adding and subtracting at the blackboard, drilling with flashcards, completing workbook problems and rearranging groups of buttons. Gabrielova walks the aisles, keeping up a brisk patter, pushing her small charges with exercise piled on top of exercise. A sense of shared purpose in her classroom is hard to miss: No one is staring out the window, talking back or disrupting things.

“They like math,” the teacher says when asked how she runs such an orderly enterprise. “Since most of them could already count up to 5 before they came here, sums are easy for them and they get good results. And if you’re successful, you tend to be enthusiastic.”

Gabrielova’s first-graders are nothing exceptional by Czech standards--but then, Czech standards are exceptionally high.

The Third International Mathematics and Science Study--an international comparison of academic achievement--found that Czech seventh- and eighth-graders were among the world’s highest scorers in math and science. Virtually the only countries performing better were in the Far East, where the world has come to expect such excellence. In Europe, only the Flemish-speaking area of Belgium gave the Czech Republic a run for its money in math.

American seventh- and eighth-graders were way down in the rankings, behind not only the Czech Republic but also such unexpected crossroads of learning as Bulgaria and Russia. The United States fared somewhat better when the study rated third- and fourth-graders, placing third in science--but falling far behind in math. A rating of high school seniors is scheduled to be published this month.

The international comparisons raise tantalizing questions for American parents and teachers: What magic is being worked in this former Communist country’s dilapidated schoolrooms, where the principal has a way of coming into a class and turning off the lights to save on electricity?

Can a young democracy, struggling to adjust to the post-Cold War world--a country where a truck driver now earns more than a top-flight physics researcher--offer any lessons for the United States, a font of wealth, great research universities and more than its share of Nobel laureates?

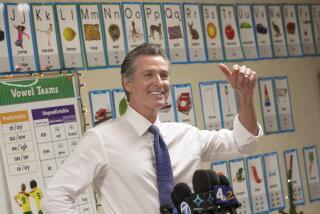

Some Clues for California Classrooms

While the Czech experience doesn’t suggest a single solution, a few days in the classrooms here do yield some clues for California, especially now, when the state’s academic standards commission is trying to balance the desire to maintain academic rigor with the wish to make science “accessible” to the masses.

Last month, the commission voted to let a team of big-name scientists work with an educational policy group based at Cal State San Bernardino on a set of science instruction guidelines for kindergarten through 12th grade. Earlier, the scientists had blasted the Cal State group for “dumbing down” science in the name of making it appealing.

A similar battle was fought over math instruction. There, the state Board of Education overruled the standards commission and voted in favor of a controversial back-to-basics document that insisted on having students memorize formulas and multiplication tables and arrive at correct answers without calculators.

The Czech example, for better or worse, seems to give some support to the no-pain-no-gain view. Few here think school should be a “fun” place where students like their subjects. What you find instead is frequent testing, an unforgiving grading system, a national set of standards, the expectation that students memorize formulas and equations, and a pervasive understanding that in the classroom the teacher has the last word.

“In Czech films, the teacher is always portrayed as the enemy,” notes Petr Chaloupka, a 20-year-old mathematical physics student working on his bachelor’s degree.

Chaloupka is sitting in the cramped, cluttered physics lab of the Zborovska Gymnasium, a magnet school for young Czechs gifted in math, physics, English and German. The building is a sad reflection of Czech public finances after four decades of communism: Dating from the turn of the century, it has never been renovated, and the physics lab is a narrow, barrel-vaulted cubbyhole. The acoustics are so wanting that the students couldn’t hear one other until someone got the idea of gluing egg cartons all over the ceiling.

A Year in Virginia as an Exchange Student

One thing the Zborovska Gymnasium does have, however, is an unmistakable Old World sense of decorum: When physics teacher Zdenek Kluiber enters the lab, his students rise and shake his hand.

For Chaloupka, it’s easy to spot the differences between his Czech classrooms and their U.S. counterparts. He spent a year as an exchange student at a high school in Fairfax County, Va. There, he says, he was surprised to find friendly, approachable teachers, multiple-choice tests--they don’t exist in the Czech Republic, he says--and an unfamiliar phenomenon called school spirit.

“When I was in the States, I enjoyed school much more,” he says. “I had much better relationships with the teachers. They were more like friends. I don’t know if it’s better, but it’s different.”

A Czech school, far from cultivating a climate of friendliness, maintains a culture of anxiety, says classmate Lukas Kroc, 18. He spent an exchange year in a small town near Austin, Texas.

“Here, I am quite afraid of exams,” he says. “I’m nervous before class.”

That’s because each day, in each subject, one student is ordered to the front of the room for an oral examination. The rest of the class listens as the students recite or solve a problem--or make spectacles of themselves.

“Imagine if you have five subjects a day, and you don’t know in which subject you’ll be called,” Chaloupka says. “You have to be ready every minute, for everything.”

Kroc adds: “Sometimes, it’s only once in a semester that you’re called on. If you’re having a bad day, it’s just too bad. If you go to the teacher and say, ‘Can’t you test me again?’ he’ll say, ‘No, it was your responsibility to be prepared.’ ”

It isn’t just the fear of public humiliation that drives young Czechs to succeed in these unscheduled moments at the blackboard. It’s also the understanding that their solo performances make up a significant part of their permanent school record.

“Our second-biggest grade is on these oral examinations,” Chaloupka says.

Along with these random oral exams comes a massive amount of rote memorization, and not only in math and science.

“We had a test here where I had to know the names of 200 authors and their texts,” Chaloupka says. “We had to know what the author wrote, but we didn’t have to read a single line of it.”

By contrast, he says, “in America, we spent a whole month reading ‘Huckleberry Finn’ and talking about it.”

Although Chaloupka and his classmates like this American approach to literature, they believe there’s no substitute for brute memorization in the abstract sciences.

“In Texas, my physics teacher wrote the formulas on the board, and you plugged in the numbers and got the results,” says Kroc, shaking his head. “I don’t believe that’s the best way. In physics here, you have to memorize all the formulas. When you’ve memorized the formulas, you can work very fast.”

Czech educators say that today’s high-pressure teaching methods can be traced to the imperial age in Europe, when their country was engulfed by the Austro-Hungarian Empire and was bordered by German speakers in Germany and parts of present-day Poland. In the 19th century came a cultural revival, with Czech nationalists portraying their country as an embattled Slav enclave in a vast German realm and urging the public to strive for academic excellence in the name of asserting their own nationhood.

“A colleague of mine found a report from the turn of the century, and it showed that even then, the Czech children were the best in math,” says Jarmila Robova, a math teaching specialist at Charles University in Prague.

The Nazis couldn’t undermine this belief in the power of education, and the Communists didn’t even try.

“The [Communist] state needed lots of technical engineers so that we could restructure nature and catch up with the United States,” recalls Emil Calda, a professor of math pedagogy at Charles. “So there was pressure put on the teacher not to have any students who failed.”

The Soviet Union stepped up the pressure by pitting Eastern Bloc nations against one another in prestigious international math and science competitions. This practice fostered a “tradition of competition” that exists even now, says physics teacher Kluiber. His salary may be low, but he can still augment it with a bonus every time one of his students wins a contest.

And while much of the pressure exerted by the Communist regime has vanished, teaching specialists say a new kind of pressure has replaced it: the pressure of money. In today’s Czech system, schools get their funding--including teacher salaries--according to how many students they have. And because parents have some choice in the school their children attend, a school with a reputation for bad mathematics teaching will lose students, and with them funding.

“Since the Velvet Revolution, the pressure in the schools has been lifted somewhat, but I don’t think the standards will go down,” Calda says, referring to the country’s rapid transition from communism to democracy in the winter of 1989.

The result: pressured teachers, anxious students. The Czech experience would appear to make these unappetizing traits look like a sure-fire route to test-score success, though it is difficult in the changing economy of this post-Cold War nation to quantify how this might translate into future career success in math and sciences.

The question remains: Could the experience be emulated in the United States? Should it?

The rigid social aspects of Czech schools would never translate to American public schools--just imagine the lawsuits. But experts say the central debate among U.S. educators is how to get all schools to teach an agreed-upon body of knowledge--regardless of how the material is presented. And in that regard, the Czech Republic may offer some guidance.

“We don’t do caning, and at the moment we’re away from drill and practice, but you can still focus on serious content and not have an oppressive feel in the classroom,” says Jacob Adams of the Nashville-based Peabody Center for Educational Policy, which is working on a strategic plan for reforming U.S. schools.

Czech Model May Not Be Right for U.S.

And Michael Martin, deputy international director of the math and science study, doesn’t think the U.S. should necessarily be looking to the Czechs.

“In America, it’s much more child-centered and relaxed,” he says. “Fear works [in the Czech Republic], but people in the United States work very hard to take fear out of the system.”

Martin warns against using the study rankings to find “ideal” teaching methods, saying, “There are other things about life” that don’t show up in the numeric scores.

In fact, when many Czechs are told that their country has done well in the international rankings, they respond not with pride but with doubt.

“I think there should also be some tests analyzing how much the Czech students like these subjects,” says Libor Inovecky, a 19-year-old math prodigy at Zborovska Gymnasium.

He spent an exchange year in Minnesota, where his standardized test scores in math were the highest in the history of his host school. He grasped calculus better than even his teacher; sometimes, when she couldn’t understand a concept, she let him teach the class.

That wouldn’t have happened in a Czech classroom, Inovecky says, but he appreciated the American teacher’s style.

“She was relaxed,” he says. “That’s what’s important about teaching: to realize that you don’t always have to be the best.”

Nor did Inovecky feel intellectually shortchanged by his year in Minnesota. Whenever he found himself way ahead of the class, he says, he just worked on his own, from a textbook.

“I think the teaching in America is done in a way to really get the students to like the subject, and they aren’t so concerned about getting students to know the depth.” For him, the one led to the other: “When you have a subject as your hobby, you just do it.”

“There’s something to both ways of learning,” student Chaloupka adds. “Here, the studies are harder. The students are really pushed to learn. I think we are very well prepared. But in the United States, it’s freer. It’s left up to the students, and everyone goes as far as he wants to go.”

*

Times education writer Richard Lee Colvin in Los Angeles contributed to this report.

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

Where Czech, U.S. Students Rank

Test scores for various nations show that seventh- and eighth-grade students in the Czech Republic, which accents rote learning, frequent testing and an unforgiving grading system, outperformed their American counterparts in most categories by a wide margin in a 1994-95 international mathematics and science study. The highest possible score is 800.

EIGHTH-GRADE MATH

Singapore: 643

South Korea: 607

Japan: 605

Hong Kong: 588

Belgium (Flemish): 565

Czech Republic: 564

Slovakia: 547

Switzerland: 545

Netherlands: 541

Slovenia: 541

Bulgaria: 540

Austria: 539

France: 538

Hungary: 537

Russia: 535

Australia: 530

Ireland: 527

Canada: 527

Belgium (French): 526

Thailand: 522

Israel: 522

Sweden: 519

Germany: 509

New Zealand: 508

England: 506

Norway: 503

Denmark: 502

United States: 500

Scotland: 498

Latvia: 493

Spain: 487

Iceland: 487

Greece: 484

Romania: 482

Lithuania: 477

Cyprus: 474

Portugal: 454

Iran: 428

Kuwait: 392

Colombia: 385

South Africa: 354

*

SEVENTH-GRADE MATH

Singapore: 601

South Korea: 577

Japan: 571

Hong Kong: 564

Belgium (Flemish): 558

Czech Republic: 523

Netherlands: 516

Bulgaria: 514

Austria: 508

Slovakia: 508

Belgium (French): 507

Switzerland: 506

Hungary: 502

Russia: 501

Ireland: 500

Slovenia: 498

Australia: 498

Thailand: 495

Canada: 494

France: 492

Germany: 484

Sweden: 477

England: 476

United States: 476

New Zealand: 472

Denmark: 465

Scotland: 463

Latvia: 462

Norway: 461

Iceland: 459

Romania: 454

Spain: 448

Cyprus: 446

Greece: 440

Lithuania: 428

Portugal: 423

Iran: 401

Colombia: 369

South Africa: 348

Source: IEA Third International Mathematics and Science Study

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.