Asia Crisis: Now for the Hard Part

- Share via

WASHINGTON — The seeming lull in the Asia crisis is only the world catching its breath as it braces for more perilous consequences in the next phase of the financial meltdown.

For starters, 1998 will reveal whether the Asian contagion is a harbinger of a looming global economic disaster akin to that of the 1920s, or more like the less severe “oil shocks,” of the 1970s.

But while the world has been riveted by the economic turbulence, the political fallout from the currency crashes, bankruptcies and impending downsizing suggests that 1998 will be a year of living dangerously from Indonesia to Korea.

The overnight morphing of the Asian miracle into the Asian mess already has destroyed the bedrock assumption that investors, political analysts, regional elites and their citizenry operated under for the past two decades: continued economic growth. Worse still, in a time of generational leadership change, it has zapped the once buoyant confidence of Asian tigers who boasted of a coming “Pacific Century,” plunging these nations into uncharted waters, with little more than the International Monetary Fund as a compass. Now their only certainty is that the old, state-directed, “catch-up” capitalism is a formula that no longer works.

While the world marveled at almost three decades of uninterrupted economic growth in many Asia-Pacific countries, these societies managed to compress economic development that took more than a century in the West into a generation. In 1960, South Korea, for example, had the same annual per capita income as the Congo: $150. Before the collapse, it enjoyed an annual per capita income of $10,000, the 11th largest economy in the world. In South Korea, as in Southeast Asia, much of the population is under 35 and has never known recession or an economy under intense external pressure.

In varying degrees, many Asian governments’ legitimacy rested on their performance. Corruption, crony capitalism and curbs on individual rights were tolerated because the pie got bigger every year. Now the old social contracts must be rewritten. Ethnic tensions, which scarred Southeast Asian nations such as Indonesia and Malaysia in the 1960s, had been largely overshadowed by the burgeoning prosperity. These tensions may now bubble to the surface again.

The fledgling middle classes that Asia’s success produced now are seeing their hopes shattered by plummeting stocks and their savings cut in half overnight by shriveled currencies. Recent migrants to megacities, like Jakarta and Bangkok, who had been sending money back to their home provinces now are returning home themselves, jobless and despairing.

The coming year will test former House Speaker Thomas P. “Tip” O’Neill Jr.’s dictum that “all politics are local,” as political leaders seek to mitigate the pain inflicted by the forces of globalization. Nowhere is this more true--or more closely watched--than in South Korea, where many fear the sheer size of its debt (at least $150 billion) could spin out of control and wreak havoc on the world economy. In addition, the military threat from an imploding North Korea adds a security dimension. This is why international banks last week rolled over some of South Korea’s short-term debt and a U.S.-led initiative accelerated delivery of $10 billion of the $57 billion in bailout funds.

But deeper turmoil in South Korea is all but inevitable. The country’s first elected opposition leader, Kim Dae Jung, must go after the conglomerates known as chaebols that dominate the economy and, at the same time, persuade his base support of militant unions and rancorous students to absorb the pain of downsizing. That South Korea has gotten past the first stage of crisis--one marked by denial and indignation--was evident last week: Its National Assembly passed 19 new laws regulating, liberalizing and making more accountable the financial sector--legislation it refused to pass only weeks before. Nonetheless, it will be a tumultuous two to three years before a more competitive South Korea begins to restore the prosperity it had come to expect.

In Southeast Asia, the crisis already has brought down one government, in Thailand, suggesting that a silver lining may be a strengthening of the region’s young democracies. But the displacement of Thailand’s low-wage laborers and the growing income disparities will be exacerbated by slow growth over the next several years. Intervention by the aging King Bhumibol Adulyadej, the nation’s ultimate political arbiter, could well be necessary to quell discontent before the Thais complete their restructuring.

But the biggest question mark in Southeast Asia is Indonesia, the world’s fourth largest nation with 200 million people. In recent years, 76-year-old President Suharto’s technocratic-led government had degenerated into a corrupt, crony capitalism that enriched his family and friends and fostered growing resentment. In the past year, there has been labor unrest and anti-Chinese riots. (Ethnic Chinese, 4% of the population, control 60% of Indonesia’s wealth.)

Suharto had planned to run for a fifth term this year, but his future is now in doubt and there is no succession process or obvious successor. All this means almost certain political upheaval, potential human-rights abuses and conflicts with the U.S. in the year ahead.

Perhaps the biggest disappointment, so far, has been Japan’s political inertia in response to its financial crisis. With an economy seven times the size of South Korea, Japan could be the locomotive that pulls Asia into a new era. But, so far, it has taken the low road, apparently willing to risk new trade tensions with Washington and export its way back to growth. Despite up to $300 billion in bad bank loans and an economy near recession, Prime Minister Ryutaro Hashimoto has been a day late and a dollar short in the steps taken so far. He has failed to override entrenched bureaucrats and accelerate deregulation of Japan’s financial markets. Hashimoto’s popularity rating has fallen to 35%, yet Japan’s political system is so inert that the opposition party disbanded in the midst of all this.

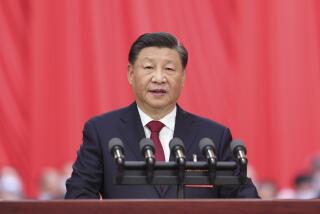

Finally, the large shadow hovering over Asia’s malaise is China which, so far, has been insulated from the crisis by the inconvertibility of its currency, large direct foreign investment flows rather than bank loans and little short-term debt. Yet, China’s banking system may be in worse shape than the rest of Asia. Bad loans may be as much as a third of China’s gross domestic product, almost four times that of Japan! And these banks have propped up state-owned industries that soak up two-thirds of domestic investment, yet produce barely 12% of China’s annual wealth.

The Asian crisis has crushed China’s hopes of transforming its economy via the model pursued by South Korea and Japan. Ironically, five years from now, we are more likely to be worried about China’s ability to hold together than the ominous “China threat” now being debated.

What does all this add up to? It suggests an Asia-Pacific that likely will be tumultuous, inward-focused, resentful and economically nationalistic as it copes with the pressures of globalization. But it also means a stronger more competitive new Asia that will emerge from its painful restructuring to pose new challenges and offer new opportunities for the United States. The problem is getting from here to there without intervening catastrophes.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.