Analyzing the Chill Factor

- Share via

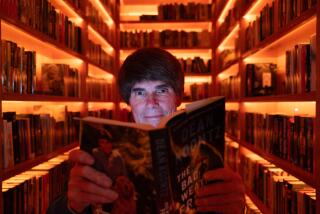

As a best-selling master of suspense, Dean Koontz has terrorized millions of readers with a chilling gallery of unfeeling psychopaths and twisted tormentors.

But the most fearsome boogeyman in the Newport Beach author’s own life was all too real: his father.

Ray Koontz, according to a new biography that examines Dean Koontz’s life and work, was a smooth-talking dreamer and schemer who had difficulty holding down a job, was prone to depression and drank excessively. He also had an explosive temper, provoking fights in bars and flying into unpredictable rages at home.

For Dean Koontz, growing up in a small town in rural Pennsylvania in the 1940s and ‘50s was a time of endless rounds of anger and threats from a father whose mere presence filled their small, two-story frame house with palpable tension.

“It wasn’t just that you knew he was in the house, you could feel him,” Koontz told biographer Katherine Ramsland. “He would never say he was going to kill us, but he’d say we’d all be better off if we weren’t here. He’d say things like, ‘There’s no future for this family anyway,’ and you knew what he meant.”

Four decades later, Koontz’s father would be diagnosed as a borderline schizophrenic, an organic disease marked by unpredictable moods and bizarre behavior and preoccupations.

Ray Koontz died in 1991 at age 81 in an Orange County nursing home that accepted psychiatric patients, but not before threatening his only child with a knife on two occasions and leaving Dean questioning whether Ray was his biological father.

“His exposure to this man who seemed larger than life in the most chaotic way left a lasting impression on Dean and his work,” Ramsland said in an interview. “There’s some manifestation of Ray Koontz in nearly every novel.”

“Dean Koontz: A Writer’s Biography” (HarperPrism; $24), written with Koontz’s cooperation, explores the author’s difficult childhood, his frustrating early years as a schoolteacher and his struggle to build what has become an extraordinarily successful writing career.

The path from his impoverished childhood in Bedford, Pa., to his hilltop home in Newport Beach is paved with more than 70 books written under his own and 11 pen names in a variety of genres--from science fiction to Gothic romances and erotica.

In 1969, Gerda, Koontz’s wife and former high school sweetheart, offered to be their sole support for five years so Dean could quit teaching and devote his full attention to writing. “If you can’t make it in five years,” Gerda told him, “you’ll never make it.” No overnight success, Koontz received $1,000 for his first novel, “Star Quest,” a 1968 science-fiction paperback. He would write more than 40 books before achieving his first best-seller, “The Key to Midnight,” a 1979 suspense novel written under the pen name Leigh Nichols.

Today, Koontz’s dark suspense novels consistently soar to the top of the national bestseller lists, and his most recent three-book contract, with Bantam Books, earned him more than $18 million. Koontz’s first novel from Bantam, “Fear Nothing,” goes on sale Jan. 14.

Ramsland, 44, spent more than 100 hours interviewing Koontz for her book. She brought to those interviews a background steeped in studies of the workings of the mind. Ramsland, who has a doctorate in philosophy and a master’s in clinical psychology, teaches existentialism at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J. Before taking on the Koontz biography, she probed the life and work of another best-selling author, Anne Rice.

Ramsland said that after completing the Rice book, “Prism of the Night,” published in 1991, the only other writer she considered doing a biography on was Koontz.

“I like people with a dark side, so that’s always a first requirement for me,” she said. “I think because I had heard that Dean had a difficult childhood--I didn’t know the details--that was probably the first drawing card for me.”

Ramsland believes Koontz wouldn’t be the writer he is without Ray Koontz as a father.

“He might be a skillful writer, but the issues that writers always grapple with over and over and over, in my opinion, are organic in their personal experience,” Ramsland said.

Speaking by phone from her home in Princeton, Ramsland said most of Koontz’s novels “either have a villain that had his father’s personality or the theme of the unprotected child, which is his experience.”

Koontz says he valued the experience of having his childhood memories probed for the biography by someone with a background in psychology.

“There’s a lot you do realize you’re borrowing out of your own life, but it turned out to be a lot more than I ever realized,” he said in a separate interview.

As a child, Koontz found escape by reading, particularly horror and science-fiction paperbacks. At age 8, he began writing his own stories, which he peddled to relatives for a nickel or a dime.

“It was cheap entertainment for a kid that couldn’t afford much,” Ramsland said. “My sense of it from studying Anne [Rice] and Dean, who are both children of alcoholics, is it’s about using your imagination to exercise control [over some facet of their lives]: They build their own worlds and decide what’s going to happen.”

*

Koontz’s mother, Florence, a humorous, upbeat woman, served as an emotional buffer for her only child. She also provided a hard-working role model for Dean and, Ramsland said, showed him how to take life as it comes and to do it with a sense of humor.

Florence Koontz never witnessed her son’s literary success. She died in 1969 at age 53, after suffering a series of strokes that affected her mind and ability to speak. But one day near the end, Ramsland writes, Florence seemed to have something urgent to tell her son.

“There’s something I’ve got to tell you about your father,” Florence struggled to say as Dean leaned in close to hear her. “You’ve got to know.”

But before she could continue, Ray Koontz walked into the room. And with fear in her eyes, Florence whispered to Dean, “Later.”

“Later” never came, and Koontz would never know what his mother wanted to reveal. He later suspected her secret may have something to do with Ray not being his biological father.

The seed of doubt had been planted when Koontz was a child and overheard a conversation between his mother and his uncle, who always treated Dean like a son.

His fun-loving uncle, a hen-pecked husband whose wife was prone to dark moods, confided to Dean’s mother that he felt they had each married the wrong person. When Florence Koontz shushed him, Koontz’s uncle said to her, “But it should have been me and you.” Dean had always fantasized about having his kind uncle as a father, and the conversation only fed the fantasy.

The truth may be even more fantastic.

Years later, Gerda Koontz read a magazine article about the first artificial insemination experiments conducted in 1944, the year before Dean was born. That’s when Koontz began taking the possibility seriously that Ray Koontz may, in fact, not have been his biological father, Ramsland said.

Because the experiments were controversial, Ramsland writes, the physicians had used couples who were likely to be discreet: Those with no more than a high school education, childless, in the lower economic classes, and living in rural areas of Pennsylvania.

And, Ramsland points out in her book, Koontz’s “parents had always called him a ‘miracle child,’ because they had been told they could not have children. . . . Dean bore no physical resemblance to Ray; the sperm donors had been highly creative people, such as composers and writers, while no one in Dean’s family had shown this kind of talent. . . .”

According to Ramsland, Koontz contemplated a DNA test to determine once and for all whether Ray was his biological father, but he never went through with it. As Ramsland said, “The worst thing for him was to have it definitely proven that this was his father.”

Koontz has talked about his father in interviews over the years, Ramsland said, “but had never put the whole thing together in this way, in part, because he had never really been asked the really probing questions by interviewers that I asked.”

Despite Koontz’s reputation for being private, Ramsland said she found him very willing to explore things that most people consider very private. And she said, he has a “fantastic” sense of humor. “He’s very sharp, witty . . . this was a two-year project, and we laughed all the time.”

Unlike Rice, “who is more serious and definitely has that dark side,” Ramsland said, “Dean is optimistic and lighthearted and views life with humor.”

Ramsland said Koontz is a self-described obsessive-compulsive--from his propensity for neatness to his work. “He revises and revises and revises over and over until it feels really perfect for him,” said Ramsland, who discovered other Koontzian personality traits.

The man People magazine once dubbed the Titan of Terror has a fear of flying--a result, Ramsland said, of his fear of losing control.

“So that, of course, includes [a fear of] flying, swimming in the ocean--and bugs,” she said, adding with a laugh: “He’s told me some good bug stories.”

*

In researching Koontz’s life, Ramsland interviewed about 85 of his friends. One personality trait that she heard of repeatedly was Koontz’s generosity--from providing professional advice to beginning writers to helping out friends in a financial pinch to sending a box full of books and promotional T-shirts to schoolchildren who wrote him a fan letter. He and his wife also provide substantial financial support to Canine Companions for Independence, a program supplying dogs for physically challenged people.

“And he was certainly generous with me with his time,” Ramsland added. She recalled “one amazing moment” during a visit to Newport Beach to interview the author:

“He had just finished ‘Sole Survivor,’ and he said, ‘Would you want to go through this line by line?’ He thought I might find that tedious. I thought, ‘Oh, my God, this is a biographer’s dream.’ It was really fascinating to watch how he did his craftsmanship.”

In going through the manuscript over the course of several days, Ramsland said, “He was showing me the patterns of metaphors--why he might pick an image and use it to enhance the feel of the scene or the atmosphere--or showing me what he was trying to achieve with color: He’s really trying to keep a subliminal tone and rhythm going whether the reader notices it or not. I really gained so much respect for his writing from that experience.”

Koontz’s attention to detail extends to the business end of his writing career.

“He knows the [publishing] business like no other writer I ever met,” Ramsland said. “He makes a point to know people who do his PR, who do his covers. He keeps his hand in every part of it. [As an author] I learned a lot.”

At his side from the start has been Gerda, who handles the financial end of the business and serves as liaison with foreign literary agents.

*

Ramsland said that when she writes a biography of a living person, it is agreed that the subject can control his or her quotes and the facts, “but I control the interpretation.” When she finished her manuscript, she sent Koontz a copy for review before turning it in to her editor.

“He went through the finalized draft and, man, I’m telling you we worked 20 hours a day on this thing to get it in on time,” she recalled. “The very last night he was actually faxing me pages of stuff. He had a deadline at the same time--he was trying to work on his novel and also give me feedback, so it was just crazy. I had to take it in to New York to get it in when it was due. I didn’t have time to even send it.”

Ramsland will never forget the train ride to New York City to deliver her manuscript.

Halfway there, the train slowed, and as she gazed out the window she saw an incredible sight: Lying next to the track was a decapitated body.

“I had been up for many hours, and I was totally in a daze,” she recalled. “I thought I must be hallucinating this. Then the conductor came by. He saw my face and said, ‘Oh, you saw that? You must be the only one. Are you going to be OK?”’

It turns out that a man had thrown himself under the train ahead of them. Ramsland told Koontz about it over the phone after returning home from New York.

A decapitated body? The Titan of Terror didn’t seem at all surprised that the woman who had spent more than two years immersed in his life and work had encountered such a chilling sight.

“Oh, yeah,” Koontz deadpanned, “that’s going to start happening to you now.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.