A Woman Is the Hero in This Greek Myth

- Share via

It is probably not too wild a guess that the heroine of Catherine Temma Davidson’s engaging first novel is the author’s alter ego. The daughter of a Jewish American father and a Greek American mother, the unnamed narrator of “The Priest Fainted” grew up celebrating Passover and Easter, but without much interest in either. When her parents said it was up to her to decide if she wanted to continue her Saturday lessons in Greek, she couldn’t wait to quit. But now the impatient little girl has become a young woman in search of her past, particularly, as befits a budding feminist, her matriarchal past.

She never knew her maternal grandmother, who traveled in steerage from a Greek village to New York across submarine-infested waters during World War I. And, although she certainly knows her American-born mother, she wonders what Mom may have experienced as a young, single woman on a long visit to her ancestral homeland in the 1950s.

The blank spaces in her knowledge seem symptomatic of the larger condition of Greek women through the centuries: “If you are a man born into this tribe, you might be able to find yourself in the stories of the past, in heroes and glories. . . . What if you are a woman? . . . Your grandmothers and your great-grandmothers gave up their names to their husbands, went inside their houses, and were never heard from again.” The only palpable legacy of the mothers resides in customs, superstitions and recipes, like the piquant mixture of eggplant, tomatoes, vegetables, garlic and herbs--Imam Baildi--that gives this book its title.

Impeded by the silence of a dead grandmother and the reticence of a live mother, Davidson’s heroine imagines her way into their worlds during her extended visit to Greece as a college student in the 1980s. She interweaves the story of her own Greek adventures with a story of what she imagines might have been her mother’s on that similar trip about 30 years earlier. And through it all, she strains to catch an echo, however faint, of her grandmother’s voice.

Davidson begins each chapter with a tartly amusing feminist retelling of a Greek myth as a sort of antidote to the resoundingly masculine bias of Greek culture. From the early days of classical glory, it was Greek men who debated and speculated in public squares, while women stayed home. The love of one man for another was widely deemed a higher form than that between men and women. And the heroes of Greek myth sallied forth to slay monsters like Medusa and resist sorceresses like Circe.

Feeding on what few signs and clues can be gleaned, the writer’s imagination reaches back to claim, if not a family history, then a sense of kinship with the women who came before her. At the same time, moving forward with her own often foolhardy adventures in love and sex, the narrator undertakes a female version of the classic hero’s quest. Thanks to the perspective offered by her revisionist Greek mythology, she can view her reckless affair with an arrogant womanizer as an educational experience. The self-centered man is Narcissus, and she, in her infatuation, is repeating the folly of the nymph Echo. And in falling for the kind of man all mothers warn against, she is following in the errant footsteps of Demeter’s daughter Persephone, carried off to Hades by the lord of the underworld:

“Anyone who has ever been a daughter, or had one, knows what really happened. . . . [Persephone] would show her mother she knew a thing or two about life and mortality and would do it so much more elegantly than Demeter, with her . . . one hand on the corn husks, the other digging through roots. How old-fashioned--all that dirt and fertility. How much more civilized and modern the cool, pale ranks of shades, dressed fashionably in black.” Like Persephone, the narrator learns about love the hard way: by making the same mistakes made by women through the ages.

Davidson’s pungent, flexible prose serves her well, not only in her witty retellings of ancient myths, but also in her crisp accounts of her heroine’s exploits as well as in her more lyrical evocations of emotion and atmosphere.

A visit to her ancestral village sets her thinking about her mother making the same trip: “I imagine she saw what I saw: a dream village, perched on the gentlest slopes of the mountain. . . . Grape arbors straddle wooden tables where neighbors gather and chat. . . . Like a spring under a shadow, the village was the source--one way her own mother’s life might have turned out. Whatever the water whispered to her, she kept it to herself. Is it wrong for me to imagine that . . . she began to wonder . . . what had moved my grandmother, what she had had to leave behind?”

Pondering the lives of women who came before her, revising Greek myths to uncover feminist parables and chronicling a modern woman’s adventures in an ancient land, Davidson’s skillfully crafted novel proves it may be possible to forge a connection to the past by living intensely in the present and keeping one’s eyes, ears and imagination open.

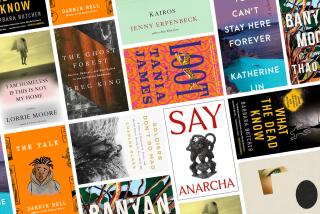

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.