USC Doctor Proposes Gene Therapy in Womb

- Share via

A pioneering USC research physician today will publicly present bold proposals to conduct the first gene therapy experiments in the womb, opening a risky and controversial new chapter in human genetic engineering.

Dr. W. French Anderson, who in 1990 did the first gene therapy experiments on a human being, is considering using two different DNA-splicing techniques, perhaps within a few years, to attempt to cure two inherited genetic diseases in fetuses.

He and his scientific co-workers are scheduled to discuss--and defend--their preliminary plans at landmark meetings today and Friday at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md.

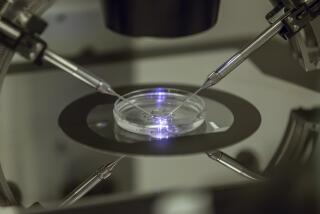

Experimental gene therapy, which involves inserting a functioning gene into the DNA of a patient to replace a missing or defective one, has been performed on about 2,000 adults and children. But scientists, physicians and ethics specialists have balked at permitting the technology to be applied before birth because of unprecedented questions and concerns.

Theoretically, the procedures to treat the two conditions--ADA deficiency disease and alpha-thalessemia--could relieve a great deal of misery if successful, but they also raise the specter of “partially” cured babies with profound defects who would not have otherwise been born.

And it hints at a new frontier where people are outfitted with engineered genes that affect not only them but their descendants, maybe for generations to come.

Anderson, director of the gene therapy laboratories at the USC School of Medicine, said he is airing these “pre-proposals” precisely to spur discussion. “What I really wanted was to have a public debate about this,” he said in an interview. “We have to take into account all the risks and benefits” before proceeding.

In some ways, the medical debate has been shaped by abortion politics. For one thing, the federal prohibition against research on embryos has hampered understanding of the precise steps in fetal development that could be vital to effective insertion of genes in the womb. Anderson said that this area of his team’s research, which has focused thus far on animals, has been funded entirely by private donations to USC.

Also, antiabortion sentiment might highlight gene therapy in the womb as an alternative to abortion for coping with a confirmed prenatal genetic defect, said Dr. Jon Gordon, a reproductive biologist and medical geneticist at Mt. Sinai School of Medicine.

But Gordon, who is a member of the NIH recombinant DNA advisory committee that is reviewing the proposals, said abortion will probably for a long time remain a preferred option for a woman known to be carrying a fetus with a genetic defect. Better to end a troubled pregnancy and hope for a normal, subsequent one, he said.

The two procedures that Anderson is proposing would be applied after prenatal genetic testing confirms a gene defect in the fetus. Beyond that, the techniques differ radically--and thus elicit different reactions from medical experts.

The one that raises the most profound questions entails injecting genetic material directly into the tissues of a developing fetus. It is intended to alleviate a rare disorder called ADA deficiency disease, so named because the patient lacks the gene for a crucial enzyme called ADA.

That can result in an immune system deficiency so profound that a child must live in an antiseptic plastic bubble to prevent deadly infections. It was this disorder that Anderson and co-workers first treated with gene therapy--achieving only limited success-- in a young girl eight years ago.

To treat it in the womb, Anderson and co-workers propose injecting a stretch of DNA containing the gene for the ADA enzyme into the fetus early in the second trimester of pregnancy. In theory, the researchers say, the foreign genetic material will induce many fast-dividing fetal cells to take up the gene, endowing the future child to overcome its inherited deficiency.

But that raises the possibility, as Anderson and other researchers say, of inserting some of the engineered gene into those fetal cells that give rise to sperm or eggs, enabling the artificial gene to be passed along to the patient’s descendants.

Although some experts argue that altering human genes for posterity would be beneficial, most oppose doing so on principle. “I don’t think our generation has the right to be putting human DNA into the gene pool until we really know it’s not going to have a bad effect,” said Dr. Donald Kohn, a medical geneticist at Childrens Hospital Los Angeles.

The Council for Responsible Genetics, a watchdog group, criticized the new proposals as “ominous” and a step toward a pernicious use of prenatal genetic engineering to create “designer babies.”

“If this first proposal is accepted,” it said in a statement, “how much longer will it be before . . . any child who doesn’t measure up to some arbitrary standard of health, behavior or physique is seen as flawed?”

Other medical experts argue against this procedure on the grounds that it is unnecessary, given that other therapies, including postnatal bone marrow transplantation, are available.

Dr. M. Louise Markert, a pediatric immunologist at Duke University and a member of the NIH panel reviewing the proposal, cited the availability of a known, effective therapy as a reason to consider another disease as a candidate for the first prenatal gene therapy.

In the other experimental procedure under consideration, the researchers would target the disorder called alpha-thalessemia, which results in miscarriages because the fetus cannot develop the vital blood protein hemoglobin.

To treat that problem, the researchers propose removing cells from the fetus in the first 20 weeks, adding the missing gene to those cells, and planting them back into the fetus. The newly endowed cells would theoretically multiply and perhaps compensate for the disease. This procedure does not appear likely to cause genetic alterations that could pass down the generations.

Among the concerns voiced about this approach is the prospect of “partial” success--a risk Anderson acknowledges. “The worst thing that could happen would be to help these fetuses to be born alive but with serious anomalies,” he said.

Several members of the NIH genetics engineering committee who have reviewed the proposals said that much further research on animals is necessary to address the outstanding questions before such proposals could be formally submitted.

“What comes through loud and clear from the scientists is that it would be premature to initiate these [experiments] because there is not enough adequate animal data,” said Ruth Macklin, a medical ethics professor at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine.