A 30-Year Journey to Same Goal

- Share via

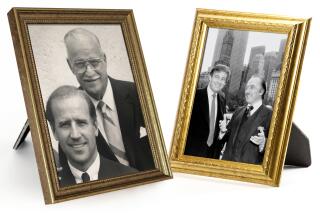

NASHVILLE — On a long November night a generation ago, Al Gore stood brokenhearted behind his father in a downtown hotel ballroom. The old man had lost his bid for reelection to the Senate, and young Gore, who had helped write the hoped-for victory speech, was overcome with despair.

His mother would say it was the only time she saw her son cry.

That same night in another hotel, this one in Houston, George W. Bush stood beside his father as he was defeated in a bid for the Senate.

The young Bush had put on a valiant face all evening, trying to convince dejected campaign aides that victory would be theirs. Finally, he too dissolved in tears.

Thirty years have passed since these sons of famous fathers were baptized in the embers of national politics. In the immediate aftermath of Nov. 3, 1970, after the pain of seeing their fathers crushed, both said seeking elective office was not for them.

Yet here they are, Vice President Gore, 51, and Texas Gov. Bush, 53, the leading candidates of their parties for the White House.

What was it about each son that led him back into the political fire, to reach for the nomination that would inevitably lead to another fateful November night?

Though each man went his own way after the defeats of that fall, both were guided by the twin themes of father and politics. It should come as no surprise then that, having been in strikingly similar situations in 1970, Al Gore Jr. and George W. Bush should arrive at the same place almost 30 years later.

In 1970, they functioned as their fathers’ sons, embracing the same political positions championed by their fathers and investing their idealism in their fathers’ success. Defeat, however, forced the sons to grow up in a way victory had not. Each man felt he had learned from his father’s mistakes and that after Vietnam and Watergate he was ready to join a new generation of national leaders.

In addition, both men were propelled by youthful self-confidence and family pride. They sought to outdo their fathers, to prove that a Gore or a Bush would not be down forever.

The journey for both men was long, begun in deep self-reflection on the morning after their fathers’ defeats.

“We talked a little bit about it and it was kind of funny,” said Donald Dean Barnhart, who served with Bush in the Texas Air National Guard. “I asked him what he thought of politics and he wasn’t very interested. He said, ‘You just don’t have much of a life if you’re in politics.’ ”

Bush instead floated through his young adulthood, working at several jobs, partying, going to graduate school. He told friends he did not want to be his father’s clone.

Gore soon shipped out to Vietnam, and he often stresses at campaign events now that his experience there soured him against politics. He was angry at both Republican and Democratic administrations for pursuing that war.

“As a matter of fact,” he said in New Hampshire last month, “I thought politics was the last thing in my life I would ever do.”

Mike Roche, his Army supervisor, once asked him about politics.

“You’ve got the name. You’ve got the good looks,” Roche told him.

“No way in hell,” Gore responded. “I’m not going into politics.”

After returning from Vietnam, Gore, much like the young Bush, explored several career possibilities. He tried divinity school and law school and worked as a newspaperman.

Yet visions of politics had danced in their heads even before 1970.

A 10-year-old Gore, watching his parents dash off for a formal White House soiree, called out: “Dad, save that outfit. I might need it someday.”

A 16-year-old Bush was thrilled by his father’s first Senate campaign in 1964, even though his dad lost that one too. The teenage Bush loved to join the Bush Bluebonnet Belles singers in belting out the campaign tune:

“Oh, the sun’s going to shine in the Senate someday!

“George Bush is going to chase them liberals away!”

But 1970 was the critical year. Even as public opposition grew to the war in Vietnam, the Nixon administration was ushering in a new conservatism in Washington. Democratic Sen. Albert Gore Sr.’s reelection campaign was an effort to stem the tide; Republican Rep. George Bush’s Senate bid an attempt to ride the wave.

A Summer Spent Absorbing Politics

Both young men, while sons of the South, had spent much of their life on the East Coast. Both attended private prep academies and each was fresh from Ivy League schools. At the time, both were in uniform.

And both of them clearly absorbed that summer the stuff of grass-roots politics, learning to meet strangers and shake hands, to speak to crowds or help write speeches.

Bush joined his father’s effort on a two-week jaunt around the state on a DC-3, hitting Austin, El Paso and San Antonio.

“If we had to stay up until 10 o’clock before we left a rally, he was still standing there shaking hands and greeting people with a smile on his face,” recalled Carl Warwick, a former professional baseball player who also stumped for the campaign.

Bob Aspromonte, another ex-baseball-star-turned-volunteer, said young Bush often spoke on behalf of his father, offering a “personal touch” to what his dad was all about.

“He was just supremely confident that he could do anything,” said campaign scheduler Dan Gillcrist. “And he had unquestioning loyalty to his father.”

Rob Mosbacher, whose own father, Robert, became President Bush’s Commerce secretary, remembered a bus tour organized with young people like himself and Bush to get out the vote.

The young George “would start talking about what his dad was like and why he would be an excellent senator,” Mosbacher said. “And he could explain his father on the issues.”

Gore Asked to Write Victory Speech

Gore, an Army private then stationed at Ft. Rucker, Ala., worked behind the scenes in his father’s campaign. He had helped write the senator’s pivotal anti-war speech at the 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago and this time was assigned to draft a victory speech.

Father and son also teamed up for television ads. In one spot the senator rode up on a white horse and told Al, “Son, always love your country.”

The pair were seen together in campaign photos too, the son in uniform. And when young Gore could not be in Tennessee to shake hands, he sent his new bride, Tipper, in his place.

“My husband is . . . frustrated at being left out of the campaigning and is happy that I’m working for his family,” she told the Memphis Commercial Appeal. “He’d never let me leave for any other reason.”

Gore flew into Nashville on election day and quickly huddled with his family and campaign advisors in a top-floor suite at the old Hermitage Hotel. Gore busied himself writing a victory address, even as the early polls showed that his father would never deliver it.

The senior Gore, a 30-year fixture in Washington, was defeated by Republican Rep. Bill Brock, who hit him hard on his opposition to the war in Vietnam and with allegations that he had lost touch with the concerns of Tennesseans. Gore lost by 4 percentage points.

“It was a pretty subdued night,” recalled Gore family friend Steve Armistead.

Down in Houston, at the Shamrock Hilton Hotel, the early vote tallies were equally disappointing, as was the rest of the evening.

The senior Bush, then a two-term congressman, had hoped to run in the general election against the Democratic incumbent, Sen. Ralph Yarborough, who was seen as far too liberal for Texas. Instead, his opponent turned out to be Lloyd Bentsen, a conservative Democrat who siphoned off the Democratic votes Bush needed to win. Bush lost by 6% of the vote.

The Bush family and campaign entourage were ensconced upstairs, but down below a determined son hung tough.

Even two hours after a television network projected that Bentsen would win, young Bush was proclaiming, “We’re still sky high and planning a victory speech.”

A Houston Post reporter, marveling at the young Bush, described him as “a carbon copy of his father, the staunchest holdout.”

Peter Roussel, the campaign press aide, remembered him this way:

“He was down in the ballroom, on the phone to me feeding me results. The early network projections showed Bentsen winning. Upstairs in the suite, we began to slump down in the sofas.

“But it’s very vivid in my memory, him telling me to hang in there, ‘You hang in there, we’re going to win this thing!’ ”

Then his father came downstairs and conceded defeat. Beside him stood his family.

“There were tears all around,” recalled Warwick. “This is a solid family, and they are all behind each other.”

Before the night ended in Nashville, Gore’s father addressed a solemn ballroom at the Hermitage. He too was surrounded by family, and they also were disheartened.

What struck some in the crowd was the pain in young Gore’s face.

“He was upset. . . ,” recalled family friend Edward S. Blair. “I don’t think Al cared one way or the other about the election at that point. But he and his father were real close, and he was hurt because his father was hurt.”

In the weeks after his father’s defeat, Bush knocked around Texas. He took a job at a Houston plant nursery and talked to owner Robert Gow about what he should do next. He toyed with the idea of running for the state Senate before quickly deciding against it.

Sometimes he showed up at Warwick’s real estate company in Houston.

“He was trying to decide what he wanted to do,” Warwick said. “Since his dad had just lost, he didn’t want to bother him. But he was looking for some new direction for himself. He was trying to figure out where to go.”

For Bush, that was a long time traveling.

“George W. inherited his father’s gift as a politician,” recalled Warwick. “He just didn’t know it yet. And he never had any dream of getting in politics himself. Back then he was just a youngster coming around and showing up at my office at lunchtime.”

Bush went to Harvard and got a master’s degree in business. He returned to Midland, Texas, and the oil and gas business, just like dad.

His entry into politics was triggered by a combination of events.

“I had inherited an understanding of the importance of public service, and I was deeply concerned about the drift toward a more powerful federal government,” he says in his new autobiography, “A Charge to Keep.”

Bush Establishes His Own Style

Even in his earliest political days, Bush’s political views were pragmatic. In 1978, Bush and his West Texas friends and business partners were upset about new legislation regulating the gas industry.

“If the federal government was going to take over the natural gas business, what would it set its sights on next?” he wondered.

The group “went around the table” looking for a candidate to run for Congress, and it fell to Bush. He won the primary but lost the general election.

Yet once he staked a claim in politics, he established his own style.

Rita Clements, wife of a former Texas Republican governor, had put together the Bush Bluebonnet Belles in 1970. She said Bush became a more hardheaded politician than his father.

“If he picks the wrong person, he’s good at getting rid of them,” she said. “President Bush never wanted to upset anybody.”

The elder Bush was immensely pleased when his son first ran for public office in 1978, even though he lost in that debut bid for a seat in Congress. “I’m tickled pink about this,” the senior Bush wrote a friend.

Robert Mosbacher, the former Commerce secretary, said that by the time young Bush entered politics he campaigned much differently than his father had in 1970.

“He learned a lot of good things,” Mosbacher said. “He learned how important issues are, and leadership, and he learned too that you have to communicate more often and perhaps more openly.

“If his father had shown the same charisma all the time publicly that he does privately, he’d [have won reelection]. I think George learned that too.”

Gore Also Learned From Father’s Defeat

Added Gillcrist, another aide from the 1970 campaign: “There was a hardening process that went on. He’s tougher. He’s got more street in him than his father.”

In 1994, his father now an ex-president, Bush ran for governor of Texas and won.

Gore likewise learned from his father’s defeat.

He came home from the war and studied religion, worked as a reporter and went to law school. But he was restless and brooding, and while he once believed he could change the world through journalism, he soon found it unrewarding. He was disillusioned when a local official he had helped expose as corrupt escaped serious punishment.

“He was a totally different person to be around,” said his Tennessee childhood friend, Armistead. “I could always draw a sense of humor out of him, and now I couldn’t get it out of him anymore.”

Politics still gnawed at the back of his mind. He was proud of his father’s accomplishments in both the House and the Senate. At his father’s funeral last year, Gore cited his dad as the greatest influence on his life.

“He respected his dad, and Al is a lot like his dad,” Armistead said.

Gore got the nudge he needed one day in 1976, when his editor at the Nashville newspaper called him with a heads-up that the local congressman from his father’s old central Tennessee district was retiring. Gore telephoned friends at night. He had them over to his house. He sought their input.

“That’s the first time any indication was made that he was going to get involved in politics,” said his friend Blair.

Of course his father was proud. “It took my breath away,” he once said, seeing his son declare his candidacy on the same Tennessee courthouse steps where he had entered politics long ago.

But young Gore, as a candidate, kept his father out of the race, not even letting him campaign on his behalf. “I don’t want anyone to vote for or against me because my name is Albert Gore,” he told voters.

While his father had been seen as too liberal and bitter about the Vietnam War, Gore was more repentant, saying it was time to “learn from the lessons” of that war.

And once elected, and mindful of how his father was criticized for losing touch with voters, Gore repeatedly returned home for town meetings, sometimes as many as five a week.

As he runs for president today, he is criticized as too formal, too stiff--so unlike his father. He knows that, and sometimes tells crowds that his father had once been one of the best orators in the Senate. “I used to love to go up there as a young boy and sit and listen.”

Gore did not come gently to politics. The night his editor called, he hung up the phone and, as his initial preparation for the race he planned to enter, fell to the floor and began doing push-ups. And moments before making his announcement speech, his stomach in knots as he was about to embark on yet another career, a nervous Al Gore threw up.

Unlike Bush, Gore’s first attempt at politics was successful. He moved to Washington, where he has been ever since, a string of victories taking him from the House to the Senate to the vice president’s mansion. Not since his father’s bitter loss so long ago has he known personal defeat on election night.

Researcher Lianne Hart in Houston contributed to this story.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.