Readers Remember

- Share via

I spent a good portion of my childhood on the streets of the east side of Milwaukee. There were all sorts of impromptu games of Kick the Can, baseball and touch football.

The first task to start the game was to choose a portion of the street that was relatively free of traffic and fresh horse droppings. Then we had to establish goal lines and boundaries. Sewers and trunks of the stately elms that lined the streets served nicely. Then we made ingenious rules to deal with the uneven numbers of entrants and their widely different ability levels.

Of course, it is all gone now, including the elm trees--victims of the Dutch elm disease epidemic that swept the Midwest in the 1950s.

JOHN SCHULTE

Banning

*

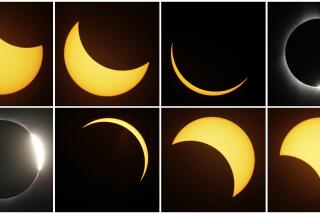

The air raid siren wailed all clear. Jostling noisily in our schoolyard in this wartime capital of Chungking that cold December afternoon in 1941, I was among my middle school classmates gathered to view the solar eclipse.

My parents had sent me there from a coastal town to escape the oncoming Japanese army. I was never to see them alive again. For half my young life, the Japanese had been bombing our cities, schools and hospitals.

That afternoon, no sooner was the eclipse over than our principal announced the stunning news of the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor. In empathy we cried. Yet we also cried with relief. China had fought the atrocities of the invading Japanese for five years. Now we would have as our ally the world’s strongest nation.

We would prevail. Victory was in sight.

We had just witnessed the total solar eclipse, we could foresee the doom of the Empire of the Rising Sun.

KATHERINE L. CHEW

Irvine

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.