The Search for Mary Murphy

- Share via

Some time in the 1930s, Mary Ellen Murphy, my great-aunt, had a falling out with her family and left her New Jersey home for parts unknown. She was never heard from again.

Although I did not know her, it was impossible to forget her. Her name was mentioned all the time around my house. After all, my grandfather, her brother, married a woman named Mary Ellen. They named their only daughter Mary Ellen. Three Mary Ellen Murphys, two a major part of my life, one a complete mystery.

Except for the box. The only concrete evidence of her existence was a simple wooden box made for her by her father. Into the lid, my great-grandfather had carved the initials M. Murphy, so all would know to whom the little treasure chest belonged. The craftsmanship was exquisite. He must have loved her deeply, I thought when I saw the box, to have made something so beautiful.

Over the years, I tried to guess what made her leave. Had she fallen in love with someone her father would not accept? Was she running to--or away from--something? Removed from the restraints and expectations of her family, who might she have become? Maybe she tried to find them again, only to be defeated by the sheer volume of Murphys, who populate the United States in greater numbers than can be found in Ireland.

When I went into journalism 20-some years ago, my grandfather asked me if I could find her. I told him, sure, but did nothing. Hunting down lost relatives didn’t interest a young reporter with visions of Watergate dancing in her head.

Years later, my father made a similar request. He had fond childhood memories of his aunt--he thought she might have been an English professor before her disappearance--and he hoped I would solve the family mystery. This time I had more interest, but no idea how to pursue such a quest.

In the intervening years, my grandfather and father have both died. I was looking through some old family papers recently and ran across my great-aunt’s name and birth date. Realizing she would be 101 if still alive, my curiosity was piqued once more.

I wanted to know more than ever what happened to her. I wanted to close the book on her, and in some way reclaim her and her severed life for my family. Without her, I couldn’t help thinking, we Murphys were incomplete.

And so, one night after I put my children to bed, I went to my computer and dialed into the Social Security Administration’s death registry. My fingers tapped timidly on the keyboard: Do you have a Mary Murphy? (For some reason, it would not accept her full name.) Yes, the other computer answered within a second. More than 3,700 of them.

All right, I told myself. Start searching.

The computer let me call up only 10 names at a time, and I had to scroll through all 10 to request the next batch. Looking for a matching birth date, I scrolled through 350 names before, two hours later, I gave up for the night.

The next day, I returned to the computer. “I will get to 1,000 today,” I told myself. Either because of my inexperience with computers or because of a glitch in the program, I had to go through the first 350 names again before I got to fresh ones. More time lost.

Finally, at 900-and-something, there was a match. I stared at the computer. There was no way to know from the scanty information on my screen whether this was my great-aunt, but the person with the matching birth date had died in December 1975. In, of all places, Santa Barbara.

I pushed a button that told the computer to print a letter to Social Security requesting information on the individual. Then I wrote a check for $7, mailed the letter and waited.

Six weeks went by and finally there was a reply, containing a copy of the person’s application for a Social Security number. She used the name Mary Ellen Kirkwood and shaved six years off her birth date. But she told the truth about one thing that set her apart from the other 3,700 Mary Murphys: She listed her parents’ names as John Edward Murphy and Ellen Walsh. Those are my great-grandparents. I had found my great-aunt.

I studied the application. It was handwritten, filled out on April 29, 1944, in McNary, Ariz., a town I had never heard of, though I lived in Arizona for a dozen years.

She listed her address as the Lumber Mill Inn. I tried to imagine how she wound up there. Was she a drifter, with no permanent home? I had believed she left to escape her family. Maybe exile became her way of life. Or maybe, as my father thought, she was a teacher. The sort who preferred the simplicity of the boarding house. I had dots on a page, but could not guess how to connect them.

Then she died on Dec. 19, 1975, so close to where I now live.

I am grateful for two things I found out about her. Sometime before she died, she reclaimed the name Murphy and came clean about her birth date. Had she not done those things, I never would have found her.

I presume she took the latter action so she could collect her Social Security benefits six years earlier than she would have under her fake birth date. Why she went back to Murphy I have no clue.

Was Kirkwood the name of a former husband? Or was it just a name she took so her family could not locate her?

Again, my imagination is at work.

I plan to obtain her death certificate from the state, look up her obituary, visit her grave. Were any survivors listed in the newspaper? Will the obituary state her occupation? Is there anyone alive who knows why she walked out on her family?

I wanted to close the book on my great-aunt. Instead, for me, her death opened the first chapter of her life. In one way, I have reclaimed her. In another, she remains out of reach, and perhaps will always be so.

*

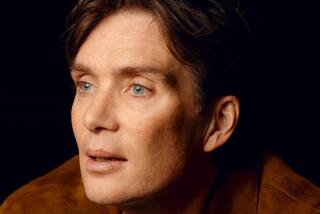

Barbara Murphy is a freelance writer.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.