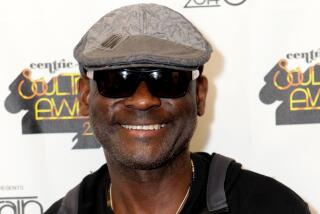

Charles Brown; Influential R & B Singer, Pianist

- Share via

Charles Brown, the veteran blues pianist and velvety balladeer whose career rebounded in the 1990s after decades in the doldrums, died Thursday in Oakland of congestive heart failure. He was 78.

Brown gained fame as a blues artist in the 1940s, starting with a landmark 1945 record, “Drifting Blues.” That was the first in a string of hits that included “Merry Christmas, Baby,” “Trouble Blues” and “Black Night.”

By 1950, he was the biggest name in rhythm and blues on the West Coast, influencing a generation of R & B and blues singers, among them Ray Charles, Sam Cooke, Fats Domino and Chuck Berry.

Bonnie Raitt, who introduced Brown to a new generation of fans when she invited him to tour with her 10 years ago, called him a master of the blues ballad and “the most extraordinary piano player I’ve ever heard.”

“With his string of hit records in the late ‘40s and ‘50s . . . Charles led the charge for the West Coast blues explosion,” Raitt said in a statement released Friday. “He introduced the nuances of great pop and jazz singing into the world of R & B, and you’ll hear it in everyone from Ray [Charles] to Sam Cooke to Marvin Gaye.”

Brown was born in 1922 in Texas City, Texas. He was raised from infancy by his grandmother after his mother died. When he was 10, his grandmother launched him into music lessons, insisting on classical piano with a little Fats Waller-style jazz on the side. His early influences were jazz pianist Art Tatum, the Ink Spots vocal trio and bluesman Leroy Carr.

But Brown wanted to be a schoolteacher. He taught high school chemistry for a while after graduating from Prairie View A & M College and then worked for the government making mustard gas in Arkansas before moving to Berkeley in 1943. It wasn’t until he moved to Los Angeles the following year that he began to focus on a musical career.

When he arrived in Los Angeles, the vibrant scene along Central Avenue was blossoming, luring celebrities and fans to the scores of clubs and after-hours hot spots that lined the street south of downtown. Brown’s big break came when he won an amateur contest at the Lincoln Theater, the West Coast equivalent of Harlem’s fabled Apollo, with his inventive combination of Earl Hines’ “Boogie With the St. Louis Blues” with the classical “Warsaw Concerto.”

Soon after, guitarist Johnny Moore and bassist Eddie Williams recruited him for the Three Blazers. A year later, “Drifting Blues” became an enormous hit.

On his own, Brown had several more hits: “Get Yourself Another Fool,” “Trouble Blues” and “Black Night.” At the height of his success in the early 1950s, he was leading an eight-piece band and mentoring such future stars as Ray Charles, Ruth Brown, the Clovers and the Dominos.

But as rock ‘n’ roll began to explode and push his ballad-blues off the charts, Brown’s career started to slide. Problems with taxes and the musicians union hurt him further, and for the next quarter-century he was barely playing anywhere. When times were lean, he did odd jobs, including washing windows for a friend’s janitorial service in Beverly Hills.

His second lucky break came around 1987, when Raitt asked him to tour with her.

“Going out on tour with Bonnie Raitt really helped me because she saw the goodness in me, in what I was about,” Brown told The Times in 1995. “Before she was born, I was out there, being a No. 1 artist across the country. . . . I’m stronger now than I was even then.”

The tour with Raitt led to an acclaimed comeback album, “All My Life,” in 1990. Brown followed that with “These Blues,” also well-received by critics.

Brown suffered an array of medical setbacks over the last three years, spending much of the last few months in an Oakland nursing home, according to his friend, guitarist Danny Caron.

Earlier this month, friends organized a musical tribute to help cover his medical expenses. Among the artists who came to salute him at San Francisco’s Great American Music Hall were Raitt, Maria Muldaur, Charlie Musselwhite, Dr. John Rebennac and John Lee Hooker.

Brown, twice married and divorced, had no family. Services will be held next Saturday at Angelus Funeral Home, 3875 S. Crenshaw Blvd., Los Angeles, and burial will follow at Inglewood Park Cemetery. Donations can be made to the Charles Brown Trust, 1311 Spruce St., Berkeley, CA 94709. Any money not needed to pay medical and funeral costs will be donated to a charity in Brown’s name.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.