Britannica Gives In and Gets Online

- Share via

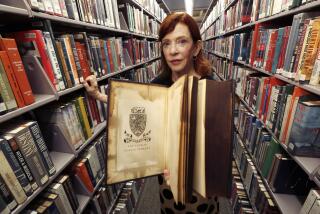

For more than two centuries, Encyclopaedia Britannica was the standard-bearer collection of knowledge in the English-speaking world, sold only through its own sales force at a premium price.

But now the publication is on the verge of becoming the buggy-whip manufacturer of the Information Age.

A shell of its former self, Britannica is taking the risky step--starting today--of posting the entire contents of its 32-volume set on the Internet for free. It hopes to make money by selling advertising on its Web site, a well-worn but still unproven business model.

“There are so many sites competing for your attention that to try to rise above the noise and cacophony is going to be extremely hard,” said David Sanderson, head of the electronic commerce practice at consulting firm Bain & Co. “This is going to be very, very tough for them to do.”

It is a risk Encyclopaedia Britannica officials feel they must take.

At its peak in 1989, the Chicago-based company had revenue of $650 million and a sales force of 2,300. The privately held concern no longer releases financial results, but officials concede that sales have dropped precipitously, and the work force today numbers just 350.

Industry experts say that with its powerful brand name, Encyclopaedia Britannica might have ruled the Internet. Instead, it has lost its online birthright to young companies that have oddball names like Yahoo Inc., which Wall Street currently values at $44 billion.

The decline of the 231-year-old Encyclopaedia Britannica “illustrates how the most stable of industries, the most focused of business models and the strongest of brands can be blown to bits by new information technology,” a pair of management consultants write in a new book, “Blown to Bits.” The first chapter of the book on corporate strategies, which was published earlier this month by Harvard Business School Press, is devoted to Britannica.

Now Britannica is hoping to transfer its unimpeachable reputation as a source of information from the paper world--where its product sells for $1,250--to the online realm. Although the Internet contains more information than could ever fit in any encyclopedia, digital or otherwise, the quality of that information is often dubious. And for researchers--an important potential online market for Britannica--it’s not always clear that the information available on the Internet is complete.

“For extensive analysis of information, I’m more likely to check print sources first and then supplement that with the Web,” said Harriet Henderson, president of the Public Library Assn., an 8,500-member group based in Chicago and a division of the American Library Assn. “It’s a mistake to depend solely on the Internet, because you can’t always find what’s out there.”

That’s exactly what Britannica, which plans a $37-million advertising campaign to spread the word about its online edition, is banking on.

“We want to become the most trusted source of information, learning and knowledge in the online environment,” said Jorge Cauz, senior vice president of marketing at Britannica.com Inc., the Internet arm of Encyclopaedia Britannica Inc. “We want to make Britannica a relevant tool for everyday use, not just archived or historical information, but information that needs to be used and trusted every day.”

The company will continue to sell both its 32-volume encyclopedia set and a CD-ROM version, feeding the steady but limited market of public libraries and institutions of higher learning.

It remains to be seen whether offering its entire encyclopedia online for free will be enough to reverse Britannica’s sagging fortunes. Many companies, from Toys R Us to Tower Records, have struggled as they’ve moved onto the Internet, where myriad young “dot-com” firms have already established themselves.

“Traditional businesses are clearly sitting on the best assets to succeed: brand names, customer relationships, supplier relationships, knowledge of the industry and merchandising,” Sanderson said. “We’re heading into Act 2, where the empire strikes back.”

Into the early 1990s, Britannica was perhaps the most trusted name in providing quality general information. Industry experts believe the company could have exploited that reputation in the online world to become a powerhouse in an era that prizes information above all else.

But like many other companies, Britannica failed to fully understand and appreciate the technology.

In the 1980s, Redmond, Wash.-based Microsoft Corp., developer of the Windows operating system that runs the vast majority of personal computers, decided that an encyclopedia on CD-ROM would help entice parents to buy a PC for the home. The company approached Britannica about licensing its name and material, but the parties could not reach a deal.

“The feeling was that we had an existing revenue stream from direct selling, and putting our content on a CD-ROM threatened to cannibalize that,” Britannica spokesman Tom Panelas said.

So Microsoft turned to Funk & Wagnalls, an encyclopedia aimed at the discount market and sold in places such as grocery stores, and developed Encarta, a splashy multimedia encyclopedia.

When Encarta was released in 1993, Microsoft virtually gave it away, arranging with PC manufacturers to have it pre-installed on millions of computers. Microsoft could afford to do that because each computer sold meant increased sales of Windows, the company’s bread-and-butter product.

Britannica, meanwhile, was selling its encyclopedias the way it always had: calling on potential customers at home using leads culled from direct-marketing campaigns and setting up shopping mall kiosks.

Britannica finally relented in 1994 and published a CD-ROM version of the encyclopedia. Critics praised its depth and detail but panned its lack of visual effects and use of technology, particularly compared with Encarta. The CD-ROMs were sold in computer stores. People who bought the printed volumes of the encyclopedia received the CD-ROM for free.

Sales of the 32-volume book sets, already in a free fall, continued to decline. But it wasn’t until 1996 that Britannica salesmen stopped making house calls.

In just five years, Microsoft had all but locked up the encyclopedia market on CD-ROM, as reviewers raved about Encarta’s ease of use and improvements in multimedia.

And just as Britannica was losing the battle in the CD-ROM market, along came another opportunity to seize leadership in the Information Age. In the early ‘90s, the Internet was giving birth to the World Wide Web. In 1994, Britannica became the first encyclopedia available on the Web.

But the company charged a subscription fee of $85 a year, which swam against the tide of free content on the Internet. Also, Britannica’s relatively dry appearance, with almost no video or audio and few graphics, made little impact in an increasingly multimedia area.

As the Web grew, companies such as Yahoo and Lycos Inc. flourished, first by indexing and searching the Web, then by giving people tailored information such as news, stock quotations, weather reports and sports scores.

Traditional news outlets, including newspapers and television networks, also jumped into the Internet, posting their own information free of charge and using their extensive advertising capabilities to promote their sites.

Soon, Britannica’s best opportunity to have a meaningful impact on the direction of the Internet had evaporated.

“They thought they were in the business of selling hundreds of pounds of paper,” said Malcolm Maclachlan, media analyst for IDC Research, a technology market research firm. “But they weren’t--they were selling information.”

Any hope for Britannica’s revival lies in the company’s name, which still resonates with most consumers, and the nearly 200 editorial employees who work on the book and online operations.

The company continues to post significant sales of both print and digital products to schools and libraries, but industry experts say Britannica needs to recapture its core market: parents concerned about their children’s future, students researching their homework and people settling bets.

Britannica will spend nearly $40 million--more than 10 times what it spent last year--on an advertising blitz that will include newspapers, radio spots and the company’s first prime-time television ads. The slogan: “What’s on your mind?”

In addition, the company’s Web site--https://www.britannica.com--has formed partnerships with 71 magazines, including the Economist and Esquire, and other information providers, including the Washington Post and the Guardian newspaper of London, that will also be made available free on the site starting Friday. Britannica will split advertising and other revenue with its partners, which also will seek to drive traffic to the site.

Some consumers, however, may have difficulty swallowing the notion of a stodgy encyclopedia publisher converting to an Internet force. While people under 30 may have heard of Britannica, chances are they have never cracked one of its volumes or visited its Web site.

But, notes Philip Evans, senior vice president of Boston Consulting Group, “in the world of navigating people to reliable and trustworthy information, one could argue, who better than Britannica? They have a brand name far better than Microsoft, Amazon or America Online for that.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.