Politician’s Spirit Soars Beyond His Helpless Body

- Share via

SCRANTON, Pa. — This is how Bill Rinaldi describes himself: a monster, a creature so different, so grotesque, that society feels threatened by his very existence.

His huge head rolls back and his blue eyes twinkle.

As usual, Rinaldi is exaggerating, pushing the limits of what people see when they first meet him, goading them into seeing something more.

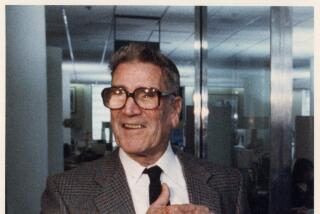

And first impressions of Rinaldi are striking: an enormous jowly face that cradles a mischievous smile, a deep authoritative voice that rumbles across the room, loud unruly thoughts that spill from his writings although he can no longer write, that burst from his paintings although he can no longer paint.

“His presence reminded them of their own potential vulnerabilities,” Rinaldi wrote in his unpublished autobiography, “and so they wanted him out of the way.”

But Rinaldi never got out of the way. He challenged convention--as an artist, poet, teacher, politician, survivor. He defied the world to see beyond the body wasted by muscular dystrophy--the “alien” of his poems--to the figure he sees in his dreams: a trapeze artist soaring over the crowds, never afraid of new heights.

The 55-year-old clerk of judicial records for Lackawanna County challenged people on a practical level too: asking them to entrust him with overseeing a department that handles hundreds of thousands of documents a year, to manage a staff of 20, even though he cannot move a limb, even though his assistants are also his bathroom attendants, even though he cannot raise his hand to take the oath of office.

Still, he gets elected every four years, often running unopposed.

*

Bill and Mary Rinaldi stake out their position early, strategically parking his wheelchair near the entrance, next to the trays of steaming hors d’oeuvres. For $100 a ticket, the Rinaldis are determined to get their money’s worth of political exposure.

Mary offers Bill a scallop wrapped in bacon perched on the end of a cocktail stick. He grimaces. He hates being fed in public. He hates when other politicians see Mary wipe his face.

His arms lie limp on the desktop in front of the wheelchair. Small, gnarled fingers curl around each other.

“Billy boy!” booms a loud voice, and a heavyset man wearing a political button strides across the room, plants a kiss on Mary’s cheek and grasps at Rinaldi’s right hand.

It falls off the tray and dangles helplessly. Swiftly Mary leans over and lifts it in back into position. Bill flashes his professional smile. The small talk resumes.

The scene will repeat itself again and again on this night and on many others.

*

Rinaldi was 2 when doctors told his mother, Rose, that muscular dystrophy would waste his muscles and probably kill him before puberty.

Take the boy home and spoil him, the doctors said. He won’t have much of a life.

That is exactly what Rinaldi’s parents did. They showered their only child with gifts, with expectations, with love.

They rounded up neighborhood kids for great big birthday parties at their house on the hill. They converted a Checker cab to carry his wheelchair. They battled the school administration to allow him to attend regular school: the first disabled child in the district to do so. While he could still use his hands, they encouraged him to write and paint.

In the 1950s, when most children with disabilities were shut away, the Rinaldis put their child on a pedestal for all the world to see. Everyone in Dunmore knew Billy Boy. And Rinaldi’s father made sure that every celebrity who came through met his son too.

Jack Kennedy shook his hand. Sophia Loren hugged him. Dean Martin pushed his chair.

Billy Boy was a star. Billy Boy was special. Billy Boy was the only kid who survived the incurable disease that killed 17 peers in the local chapter of the Muscular Dystrophy Assn.

But beneath the “cocky little kid in the body that didn’t work,” as Rinaldi describes himself, grew a rage. Rage at not being able to swat a mosquito on his hand. Rage at not being able to get into restaurants and theaters. Rage at having his father drive him to dates.

When he was 9, he strangled the family cat because it kept pestering him and because his hands still had the strength to do so. When he was a teenager, he persuaded a cousin to help him run away, just to frighten his parents. As an adult, he ran for election, just to see if people would vote for a “cripple.”

“I’m like Jekyll and Hyde,” Rinaldi says. “I have this mean, spiteful side that’s angry at the world.

“I hate that side of me,” he adds.

Those who know him say that without it, he probably wouldn’t have survived.

*

Sometimes Rinaldi finds himself lying naked in a hotel, staring at the ceiling as his attendants fuss, turning him, cleaning him, preparing him for the day.

Why, he fumes silently, must my body be the only one exposed in all its ugliness? Why shouldn’t they be naked too?

It’s taken a long, long time for Rinaldi to accept that his most intimate bodily functions must be attended to by other people.

But, he says, it’s worse for people who become paralyzed later in life. Worse to have appetites whetted and then snatched away.

When Rinaldi counsels those people, he tells them what his father and grandfather told him: Don’t put your mind in a wheelchair too.

*

Rinaldi was 32 the first time he ran for office, a schoolteacher in a wheelchair with an enormous ego and idealistic views about changing the world, or at least his portion of it: Dunmore, a town of 15,000, three miles from Scranton.

He would take on the party machine. He would show his students how democracy works. He would show them that even a disabled person could win if he worked hard enough.

Rinaldi had already proved himself a master at grabbing attention: He had been voted “most likely to succeed” in high school, had been chairman of his graduating class, had even received a phone call from Richard Nixon after writing to the president about Vietnam.

Campaigning with a group of enthusiastic students who plastered his posters around town and wheeled him to functions, Rinaldi ousted the incumbent tax collector by 200 votes. The local paper called it the “greatest political upset in Lackawanna County in over a decade.”

Billy Boy was thrilled. And petrified.

It was one thing to sit at the head of a classroom, in control, teaching government and literature. It was quite another to be accountable to voters who might see only his disability, might question his ability to do the job.

*

“People have always been jealous of Billy,” says his cousin, Annie Brokus. “They think, wow, what a great life he’s got--this guy has it all. And he is always so brilliant at everything he turns to.”

He ran muscular dystrophy telethons. He helped organize Scranton’s first film festival. He wrote a weekly newspaper column, short stories, plays that were performed by local theater groups. He worked to promote the Americans With Disabilities Act, once bouncing uncomfortably in an antechamber of an Amtrak train from Scranton to Washington, just to prove to railroad officials how inaccessible their trains were.

He mastered the computer, using the minuscule amount of movement in his forefinger to drag a pencil across the keyboard, using voice activation to write.

“The Internet gave me arms and legs,” he said. “It allowed me to explore places I could only dream of.”

But there were some things Billy Boy couldn’t explore, not even in his own mind.

“Franklin Delano Roosevelt said people in wheelchairs must reconcile themselves to their isolation or suffer additional misery,” Rinaldi once wrote. “But he had Eleanor, and I had no one.”

And then along came Mary.

*

Mary Ferrario remembers the boy in the wheelchair who sat at the top of the church. The first altar boy in the world in a wheelchair, her mother whispered, and he wasn’t supposed to live.

Twenty years later, Mary met Rinaldi at a fund-raiser in Dunmore. The boy who wasn’t supposed to live had done a lot of things he wasn’t supposed to do: graduated from college, become a teacher, written plays.

Mary was captivated. As the daughter of a prominent Democrat, she couldn’t very well campaign for Rinaldi, who was then a Republican (he later switched parties). But she rooted for him secretly. And when she heard the news on election night, she bought a red rose and headed to his house. In the midst of the hoopla, she leaned over his chair and they kissed.

“From that moment, I never saw his wheelchair,” she said. “I just saw this wonderful, courageous, interesting man who had such a huge heart and such an appetite for life.”

Rinaldi was terrified. He could push the limits in other ways, but love, marriage, being a partner in someone’s life? His own was complicated enough.

“I had spent my entire life pretending to everyone but my parents that I was physically more capable than I was,” Rinaldi said. “I didn’t want to reveal my true dependency to anyone, especially not to a woman who, no matter how beautiful, no matter how wonderful, wanted to share every last bit of space, including the only place where I ever had any privacy, my own bed.”

So, although he wrote her endless love poems, it was a long time before he said, “I love you.”

And it was 13 years before he agreed to marry her.

*

Mary pushes her husband’s wheelchair down the corridors of the ornate stone courthouse and into his first-floor office. It’s 11:30 a.m., and he has just arrived for work. Mary and several attendants have spent four hours getting him ready--exercising, lifting, cleaning him, making sure his body, bloated from lying motionless all night, functions properly.

Special preparations are also made in his office. The heater is on, even though the day is warm and sunny. Rinaldi’s circulation is so poor that he feels ice cold much of the time. For two months in winter, he runs his office from Punta Gorda, Fla. His doctors say that simply catching a cold could kill him.

Rinaldi has been the clerk of judicial records for 19 years. His office oversees all documents relating to the civil and criminal divisions of the Lackawanna County Court. The criminal division, up a narrow flight of steps on the third floor, is practically inaccessible to him. Rinaldi has been lifted there only three times.

He does most of his work propped at his desk, behind his laptop. An aide curls his forefinger around a thick red pencil and turns on the computer. He opens files, checking his calendar, meetings and documents.

Lunch is at his desk. Mary props a sandwich in his hand and sets it on top of a plastic box that reaches to his chin. When his hand is placed close enough to his mouth, he can feed himself.

Rinaldi brags that he is “just as brash and opinionated” as any other elected official. “I just have to be a little more resourceful than most.”

But he is sensitive to charges that he isn’t up to the $55,000-a-year job, charges that surfaced in a primary campaign in 1997. His opponent accused him of wooing the sympathy vote and of not putting in enough hours at work. (Rinaldi won 70% of the vote.)

His wife and mother hate the people who say such things. Rinaldi pretends not to care.

But beneath his braggadocio is ever-present fear. Fear that plans will change at the last moment, leaving him scrambling to reorganize his schedule for attendants. Fear that his specially adapted van will break down. Fear that people will see behind the polished image and realize how helpless he really is.

“Dad is most afraid when he is not in control,” says Tom Parry, Rinaldi’s 39-year-old assistant. The two men are so close they call each other father and son.

Rinaldi beams as he gazes at Parry. Sometimes he wonders: Is that the kind of man he would have been if he’d had mobility? Parry looks at Rinaldi and sees the man he aspires to be.

“He’s inspiring, he’s intimidating, he can be hard on others, but mainly he’s just hard on himself,” Parry says. “And everything is so rigidly planned. He needs to be a little more spontaneous sometimes.”

“Maybe,” Rinaldi retorts, “I’d be more spontaneous if I had arms and legs that worked.”

*

Rinaldi’s feet are baby soft, and his shoes are 12 years old. They are as shiny and polished as the day they were purchased. At night, Mary pulls them off as she prepares her husband for bed, a 45-minute ritual that includes moving and stretching his limbs, scrubbing his face, hoisting a hydraulic lift beneath the detachable seat on his chair. Puffing and cranking, she swings his 220-pound frame, hammock-like, over their bed. Rinaldi’s head rolls back; his arms and legs swing raggedly. Slowly Mary lowers his limp torso onto the bed, dumping him onto the sheets “like a load from a cargo ship,” he says. Or a monster. Mary hushes him impatiently. She hates when he jokes about his vulnerability.

Sometimes, when he gets this way, she points to the baby photographs in their home and his office, pictures of an adorable child, glowing with chubbiness, a perfect little cowlick framing his forehead.

“You were beautiful then and you are beautiful now,” she says, propping a pillow under his head and stroking his legs--the legs of an 8-year-old.

“Your courage is beautiful.”

The couple talk a little about plans for the next day and exchange a good-night kiss. Then Mary straps an oxygen mask around her husband’s face and switches off the light.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.