Now See Florida Voting Through Eyes of Disabled

- Share via

The issue of equal protection was central to the Florida election controversy, but not in the way the U.S. Supreme Court dealt with it in Bush vs. Gore. Equal protection of large classes of voters mandates the complete counting of all ballots in question. This is not as Republican lawyers would have it--as few ballots as possible--and not as Justice Sandra Day O’Connor suggested: Count only those where voters “followed instructions.”

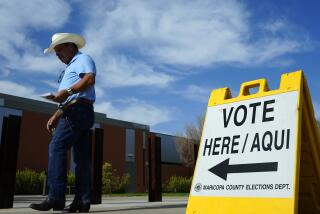

Casting a flawless ballot was more difficult for at least two sets of protected voters: people with limited reading skills, who are disproportionately minority, and people with disabilities.

Consider the “overvotes” that disenfranchised more than 100,000 citizens.

Everybody has heard about the confusion created by the bizarre configuration of the Palm Beach County butterfly ballot. Yet even those who figured it out might have been unable to deliver an effective vote, with the ballots’ closely set holes to punch, because of myopia, astigmatism, glaucoma, cataracts or imperfect eye-hand coordination.

The sample ballot in Duval County listed all presidential candidates on a single page and instructed voters to vote on every page. When they arrived at their polling places, however, they faced a ballot that spread presidential candidates across two pages. Voters following sample-ballot instructions, after registering a choice for George W. Bush, Al Gore or Ralph Nader, would turn the page, pick one of five lesser-known candidates and so void their presidential preference.

And what good was the contradictory, and somewhat obscure, new instruction in the voting booth, “Vote on appropriate pages,” to Jacksonville’s semiliterate and dyslexic citizens?

Disenfranchisement of the uneducated is not new in the South. “Literacy” tests were imposed primarily to obstruct African Americans, who were generally denied education past the eighth grade. Literacy tests were prohibited by the Voting Rights Act of 1965 because they disproportionately excluded minorities from voting. Now “stealth” literacy tests are coming in through the back door. And once again their primary victims are minorities.

Literacy in Florida’s African American community is lower than that of whites, thanks to a tawdry history of segregated and underfunded black schools. In Miami-Dade County, predominantly black precincts saw their votes thrown out at four times the rate of white precincts.

Consider also the “undervotes,” in which machines discerned no presidential preference. It appears that many voters executed their choices imperfectly, but many of these “voter errors” can be attributed to physical or cognitive disabilities.

Among the many reasons a ballot might not be fully perforated in just the right spot by a small voting stylus: Parkinson’s disease, arthritis, palsy or the muscular degeneration often associated with age.

People with disabilities have the same right to vote as everyone else. The Americans with Disabilities Act requires local governments to ensure that their programs, including voting, are usable by persons with disabilities.

In addition, the Voting Accessibility for the Elderly and Handicapped Act requires federal election sites to be accessible. Both of these laws are routinely violated, and it is likely that such violations are responsible for ballots never cast in numbers far exceeding any of the Bush margins in Florida, as well as thousands of presidential votes cast but not counted. Unfortunately, none of the attorneys or the courts reviewing the issues ever addressed this chronic equal-protection problem.

If equal protection is a collective commitment and not just a courtroom catch-phrase, its first beneficiaries must be voters--such as minorities and those with disabilities--who have been systematically excluded from shaping the world in which they live.

The U.S. Supreme Court majority built its opinion on the cornerstone of equal protection, but dismissed applying the concept to the benefit of the citizens who need it most. In laying down that cornerstone at the wrong angle, it is no wonder that the court has constructed an edifice that cannot stand in the currents of public opinion and topples under legal scrutiny.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.