David Hunter; Guided Philanthropy to Address Social Inequalities

- Share via

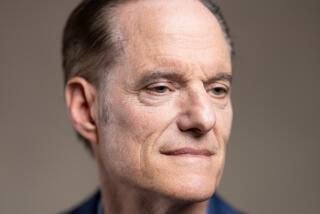

David R. Hunter, a seminal figure in progressive, socially conscious philanthropy whose guidance helped several influential foundations accomplish their mission, has died.

Hunter died Nov. 25 in Port Washington, N.Y. He was 84. Hunter was widely regarded as one of the first philanthropic officials to see foundations as an instrument for dealing with social and economic inequities.

“He was the first venture socialist,” said Eric Mann, the head of the Los Angeles-based Labor Community Strategy Center. “He wanted to fund the most influential projects, which were often the most radical.”

Hunter was an early board member of the Liberty Hill Foundation, a Southland philanthropy.

“He took us seriously and helped us with other foundations,” said Sarah Pillsbury, one of the founders of Liberty Hill. “By lending us that dignity he helped us take ourselves seriously.”

An idealist without being an ideologue, Hunter helped fund a number of progressive causes. They ranged from women’s rights to labor union democracy to nonintervention in Central America to self-help in Appalachia. An initial grant from Hunter supported work that eventually led to “motor voter” legislation that made voter registration much easier.

His reputation and courtly manner--often, among activist friends, he was the only person in the room wearing a suit and tie--gave him access to the mainstream foundation world.

But as Mann recalled, Hunter was also a hard-nosed pragmatist, with no prejudice toward specific ideology.

“He could be a harsh interrogator on issues,” Mann said. “He spoke in questions, playing his cards close to his vest. And while his personal style was conservative and introverted, his politics could be radical.”

Hunter was also willing to advance new ideas in the world of giving.

In a 1975 speech to the Council on Foundations, he said the foundations’ reason for being should be the work of “extending democracy in the world of economics as well as politics.” The speech “made half of them mad as hell,” he later told the New York Times.

Hunter studied at the University of Colorado and UC Berkeley before getting his master’s degree in social work from the University of Chicago.

Hunter entered philanthropic work in 1959 as a program officer at the Ford Foundation. With several colleagues, he devised programs for poor neighborhoods that became a prototype for President Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty.

In 1963, Hunter left Ford to become executive director of the Stern Fund, a New York-based family foundation funded by the Sears, Roebuck fortune. Hunter was simultaneously the head of the Ottinger Foundation and philanthropic advisor to half a dozen similarly minded foundations and grant-making individuals.

Hunter headed the Stern Fund from 1963 until it ceased operation in 1986 after completing its mission by giving away $25 million.

Anne Hess, granddaughter of Edith R. Stern and Edgar Stern, the founders of the Stern Fund, remembered Hunter as “a man of vision who never lost sight of what philanthropy should do.”

Mann recalled that Hunter used foundation money in interesting ways, viewing philanthropy as a way to test various solutions to social issues.

“‘He would sometimes fund several sides of an issue and come back at the end of the year for a discussion of how it was going,” Mann said. “His questions were always constructive and focused on accountability.”

Liberty Hill’s Pillsbury recalled Hunter’s sense of commitment: “He told us that social change is a long-term proposition. He had the faith that we would be in it for the long haul.”

In a speech some years ago, Hunter borrowed some thoughts from George Bernard Shaw on the notion of social responsibility.

“I am of the opinion that my life belongs to the whole community, and as long as I live it is my privilege to do for it whatever I can. . . . This is the true joy in life . . . the being a force of nature instead of a feverish selfish little clod of ailments and grievances complaining that the world will not devote itself to making you happy.”

Hunter is survived by his wife, Barbara; two stepsons, Stephen L. Moss and Daniel A. Moss; and two grandchildren, Alexandra B. Moss and Jason L. Moss.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.