Easy as Pi? Go Figure

- Share via

Hallmark hasn’t caught on to Pi Day yet.

There are no sappy sentiments: “Honey, you mean at least 3.14 times more to me than anyone else, ever--”

There are no gag insults: “I racked my brains till I thought of the perfect gift for you--Pi! In Your Face!”

No, Pi Day is one of the last American observances unsullied by commercialism--and somehow you managed to miss it.

It was Tuesday.

Pi, as you might recall, is the number that describes the relationship between the distance around a circle and the distance across it. It can be rounded off to 3.14.

Get it? Three-fourteen? March 14? Pi Day!

For many people, Pi Day will spark the same level of muted excitement as, say, County Government Day.

But with the help of skilled individuals, pi can induce feelings of surprise, giddiness, astonishment, brain fever, existential nausea, and a bizarre desire to know more about math--which explains why math instructors at Oxnard College were leading the charge yesterday at the county’s only Pi Day observance.

On folding tables set up outside the school’s clock tower, they had arrayed a display about minority mathematicians--intriguing tidbits about numbers (the biggest known prime number is two, multiplied 6,972,593 times, minus one)--and lots of puzzles.

Challenged, I tried to build a pyramid out of four odd pieces of plastic. After a couple of minutes, I quit, confident that Einstein--whose birthday happens to be 3-14--wouldn’t have trifled away his time with stupid puzzles.

Mariel Mendez, a sophomore math major, got it almost immediately.

But I was an English major (i.e.: virtually unemployable), while Mariel is eager to teach math and make a difference.

“There aren’t many female math teachers, especially Latinas,” she said. “I hate hearing little girls say they’re bad at math. They just don’t have the role models.”

But why math, I insisted, obtusely.

“Math is truth,” she said.

Modeled after an annual extravaganza at the Exploratorium, San Francisco’s science center, the college’s Pi Day observance was the brainchild of a teacher named Mark Bates--”like the motel,” as he explains.

Bates is a big fan of pi. He wore red sneakers and a shirt with the pi symbol, done in cherries. It said: “Cherry Pi.”

Nobody has gotten to the bottom of pi. Using the most powerful computers on earth, mathematicians have doped out the number after the decimal point to more than 200 billion digits, but they’re not done. Bates once had pi memorized to some 300 digits, but he said he can now recall only about 130 of them. He gives extra credit to students who can memorize 50.

“You have seven friends, right?” he asks them. “Well, you can memorize seven phone numbers, can’t you?”

Dozens of students dropped by the Pi Day tables, curious about the goings-on. Some took part in a contest to estimate the height of the clock tower, using only a calculator, a yardstick and their wits.

I gave it a whirl too, with the help of instructor Phil Abramoff, who had to point out the ‘tangent’ button on the calculator and who let me know that I managed to subtract when I should have added. I came up with an answer of 36.5 feet, just about 20% under the correct answer, as estimated by the school’s maintenance staff.

Whatever.

Students were fascinated with the problems on the table. Here’s one that reputedly took a group of astronauts 28 days to solve, although it took a class of fourth-graders 10 minutes: Fill in the three blanks at the end of these letters: O-T-T-F-F-S-S-blank-blank-blank (For the answer, send me an e-mail in a plain brown wrapper).

But it isn’t every day that such concentration surfaces in actual math classes. The teachers told a familiar story: Students are scared of math. They’re poorly prepared in high school. Many don’t know the basics--multiplication, division, percentages. One teacher said he saw a student reach for his calculator to divide 60 by 2.

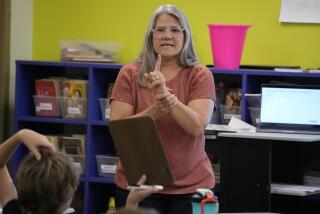

All the same, Rena Petrello, a part-time actress, said she loves teaching calculus.

“I live for the moment when the glaze clears,” she said.

And David Magallanes rhapsodized about the universality of math. “It’s the language of God,” he said.

And then, of course, there’s pi. You might call it God running at the mouth.

“It’s in everything,” Bates said, pointing to a reference in the Bible, to pi-based cycles in bird songs and brain waves, to the Indiana Legislature ruling (wrongly) in 1897 that pi equals 4.

As I packed up to leave, I was offered one of the cellophane-wrapped pies that had been given out as contest prizes.

I declined, saying it would be unethical.

Huh?

Pi-ola, I explained. It’s in everything.

Steve Chawkins can be reached at 653-7561 or by e-mail at steve.chawkins@latimes.com.