Closing the Financial Literacy Gap

- Share via

Don’t get pregnant! For heaven’s sake, no matter what you do, you vulnerable, hormone-crazed teenage girl--Do Not Get Pregnant! Assuming that a young woman heeds that message, which some days seems to be written on every billboard and trumpeted from each treetop in the urban jungle, what is she then supposed to do with her nice, strong, not pregnant self? Head a Fortune 500 company?

Well, why not?

Thirty years of feminist rhetoric has told her she could. Yet while society might, legally and attitudinally, be supportive of women in business, those who actually talk to girls, asking those nitty-gritty, “what do you want to do when you grow up?” questions, say their awareness of economic realities is alarmingly limited. High school graduates, college alumnae and even women with business school degrees are victims of a complex set of historical, sociological and familial circumstances that conspire to keep many of them financially illiterate, or at least several laps behind the boys.

An alliance of Los Angeles educational and social service groups recognized the importance of teaching girls economic literacy early, acknowledging that there were other topics worth discussing besides teen pregnancy, often a financial sand trap in itself. They believed girls needed to know about balancing a checkbook, investing for the future, managing credit card debt, thinking creatively about owning their own businesses and giving back to the community.

So three years ago, the Collaborative for the Economic Empowerment and Readiness of Girls pooled the resources of the Angeles Girl Scout Council, Junior Achievement, the YWCA, Girls Inc. and the L.A. Women’s Foundation to educate girls from 9 to 18 in some money basics. They invited 200 local high school girls to a daylong program at USC recently that included workshops, lectures and contact with mentors.

Anyone who questions whether it was a good idea to invite teenage girls to an event called “Making It: You, Your Money, Your Future” need only look at the statistics. Single women with children account for 54% of all poor families in this country. Single mothers head 19% of all families with children, but are twice as likely as married couples to live below the federally defined poverty line. One in seven women in America lives in poverty, one in three among African American women and Latinas.

The collaborative targets girls from ethnically diverse and low-income neighborhoods. But Joline Godfrey, chief executive of Independent Means Inc., a Santa Barbara-based provider of training and products for the financial novice who spoke at the conference, said that economic illiteracy is the great leveler, crossing race and class barriers. “I work in very chichi private schools, and I will often walk out of them more shaken than in an inner city school, because the privileged kids are so oblivious to how critical these issues are to their lives, even now.”

Saving for the Future and Paying Off Debt

According to a 1997 study conducted by the Oppenheimer Fund, one in seven women has nothing saved for retirement. Of those who do, one in three women with both savings for the future and credit cards owes more on her credit cards than she has in her retirement account. “Across culture and economic strata is this perverse notion that a privilege of prosperity is that the daughters of people who have achieved upward mobility don’t have to become economically competent,” Godfrey said.

The fault line separating women from financial savvy even runs through elementary school playgrounds, where boys trade marbles, then baseball cards, in informal marketplaces that acquaint them with risking, investing, absorbing losses and maximizing gains. Girls who get baby-sitting jobs are told, “You’re so good with children.” Boys who earn money mowing lawns aren’t praised for their talent with grass. They’re applauded for being resourceful and entrepreneurial.

Dana Goldinger is a real estate, finance and bankruptcy attorney who now works in insurance and estate planning in Beverly Hills. “I deal with a lot of high-net-worth individuals,” she said, “and my experience has been that many wives of affluent men have no clue about their financial situation, and the results of that can sometimes be devastating.”

Wasn’t the last wave of feminism, one of the great movements for social change that arose at the end of the ‘60s, supposed to solve these problems? “We are in a different place than we were 20 years ago, but we haven’t moved as far as we thought we would,” Godfrey said.

Twenty years ago, armed with a degree in social work, Godfrey was hired by Polaroid Corp. to counsel its employees. She became increasingly interested in becoming an entrepreneur, she said, because “I came to understand that if you really want to make an impact, you have to run the company.” She launched a firm that designed executive learning programs for Fortune 500 companies and sold it in 1990.

Then Inc. magazine, interested in taking the pulse of its readers, asked her to travel around the country to interview women who had founded businesses. The stories they told became the basis for Godfrey’s book, “Our Wildest Dreams: Women Making Money, Having Fun, Doing Good” (Harper Business, 1990).

Godfrey’s research gave her an understanding of why women achieve financial literacy late, if at all. Her knowledge has made her blunt: When asked why girls need to develop their economic consciousness, she replied, “Because if they don’t, they’re going to be poor when they’re old. That’s true for me, just like for any woman who wasn’t paying attention when she was 15 or 20. My own consciousness was sufficiently delayed so I’ve had to really hurry up and learn and make up for lost time. Very quickly, I’ve had to understand everything from my own investments to my company’s balance sheet. More than a decade ago, I began to immerse myself in the language of finance, to talk to people who were financially sophisticated. I joined an investment club. I read something related to money, business and finance every single day. But when you’re starting late to try to figure out your own economic issues, it’s like trying to learn to speak French when you’re 30 instead of when you’re 6.”

A Problem Rooted in History

There has always been a split in American culture between the champions of gradual, incremental acquisition and the gamblers. When 50 able-bodied women would rather take a chance on marrying a multimillionaire than try to become one, it’s obvious that some visions of feminine success die hard. What forces conspire against women gaining financial literacy?

* Historical realities: Women’s place in the work force has always been affected by events. During World War II, it became socially acceptable for women to work outside their homes because men were busy waging war, leaving many essential jobs unfilled. Once the soldiers returned home, June Cleaver and Harriet Nelson became role models, and women went back to the kitchen, preferably wearing housedresses and pumps.

“We had the vote for decades before we got to any conversations about equal opportunity, and then we had to spend time dealing with that, before we could get into equal credit opportunity. Then we were dealing with issues of women’s health. I see our growing awareness about women’s economic strength as what we’ll pay attention to next. Other things had to be in place before we had the luxury of looking at our own economic issues,” Godfrey said.

* Generational differences: A woman in her 30s told Godfrey about using words like “compound interest” and “asset diversification” in a discussion with her parents about her retirement planning. “Where did you learn about that?” her mother asked, as shocked as if her daughter had just revealed an intimate knowledge of sadomasochism.

Money is one big bomb that lies beneath the minefield of mother-daughter relationships. “In many families, at the heart of every conversation about money is the mother’s fear that she’ll be found out as stupid if her daughter’s economic competence exceeds hers,” Godfrey said. When a father and daughter share financial sophistication that the mother doesn’t, she can feel left out and threatened.

* The Cinderella complex: The image of Prince Charming, a great dancer who also pays the bills and doesn’t require a prenup, persists. In reality, men die, leave or wear out their welcome, and nearly 90% of all women will have to take care of themselves economically, at some point in their lives. “We live longer, and our pensions are generally far less generous, if we have them at all,” Godfrey said. “We’re generally the caretakers in the family, so we aren’t just taking care of ourselves. Although you think you will live happily ever after, you can suddenly be blindsided by life.”

Even the woman who no longer waits for the prince’s quickening kiss can have difficulty moving out of princess mode. Goldinger, the estate planner, said, “It’s not that men always know about money, but they act like they do, and if they don’t, they have a network of friends to consult. Historically, women have felt intimidated or too inhibited to ask questions about money.”

* The guilt trip: Godfrey is somewhat unusual in wanting to help girls and make a profit doing so. She has encountered many men and women who have accepted the notion that doing good and making money are mutually exclusive. Women have traditionally worked in helping professions--teaching, nursing, social work--fields in which a peculiar American ambivalence about success feeds the idea that it isn’t noble or feminine to get rich.

“Both men and women have an inner hunger to do something complex and interesting, and to give back,” Godfrey said. “They both want more than to just make as much money as they can. Happily, in our economy, there are lots of ways to be economically powerful and socially useful, if you have the skills.”

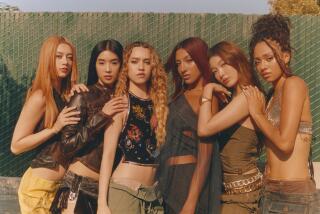

In many of the exercises Godfrey has developed, girls are encouraged to think about starting their own businesses. At the USC conference, teams were given Product in a Box, a learning game she created. Beginning with an assortment of doodads and scraps, the girls were instructed to create a product, invent a company name, decide how much they’d charge for the item, where it would be sold, and how they’d advertise and market it. They made earrings, hair gel applicators, gift boxes, decorations for a child’s room, hair ornaments, and aprons for companies they called Ghetto Fabuloso, Why Be Normal, Clowns R Us and Hair on the Go.

In a session with teachers who work with the girls daily, Godfrey admitted that the new product presentations weren’t outstanding. “They were crude, first attempts,” she said. “But no one had ever asked them to do anything like that before. With practice, they’ll get better. It’s not about the technical skills. It’s raising their consciousness so they believe their ideas are valuable, their time is worth something.”

Theresa, a 5-foot-3, 19-year-old high school senior with a 2-year-old daughter, said she’s less interested in becoming her own boss than getting a job as a model or fashion designer. With “Melrose Place” fantasies supplanting fairy-tale dreams, entrepreneurship would seem a distant possibility for many young women.

“Being entrepreneurial is a metaphor for independence,” Godfrey said. “It’s as much a point of view as a path many of them will actually take. I want to hook them on what a cool way this is to get independence, then they’ll find their own way. The qualities they need to be entrepreneurial--confidence, creativity, persistence, resiliency, self-sufficiency--are useful in many work situations. Companies need employees who think in more flexible, creative ways. That’s true for both girls and boys.”

* The Independent Means Web site is https://www.independentmeans.com.

* Mimi Avins can be reached at mimi.avins@latimes.com.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.