Wiffle Ball Hits Home

- Share via

Wiley Roberts leaned into the batter’s box, glaring as Marty Rackham went into his windup.

Rackham delivered the pitch and Roberts swung ferociously, hitting the wicked sinker deep to right. The ball sailed over the fence, a towering 77-foot shot.

The crowd, sitting in bleachers that once graced Anaheim Stadium, applauded loudly between swigs of beer, then settled back and checked a nearby television to see how the Yankees-A’s playoff game was going. And in the broadcast booth, comedians Jeff Hatz and Jeremy Kramer poked fun at Roberts, Rackham and most anyone else who came in their line of sight.

All this, in Rick Messina’s backyard.

The game: Wiffle ball. But not the kids’ game that ranks right up there with Monopoly and the yo-yo as an icon of the American scene. This is Wiffle ball for adults, Wiffle ball squared. Serious stuff, sort of.

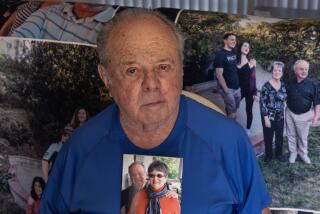

What Messina, who manages comedians, has done is take Wiffle ball to the extreme, spending a wad of cash to transform the backyard of his posh Encino home into wiffler heaven. His buddies turn up every Sunday to play ball, imbibe freely, smoke cigars and watch sports on the seven televisions that line the wall of his den. Messina even bought the house next door for $700,000 to expand his complex, filling in the swimming pool to make way for a second wiffle field and various other games played by this 40-something crowd.

“This is where every man wants to be if he could,” said bachelor Messina, 45, whose clients include comic superstars Drew Carey and Tim Allen. “I could have bought a home in Colorado that I’d use once a year, but I get to do this every weekend.”

While Messina may take his Wiffle ball to the outer limits, he is not alone in taking the game very seriously. This may be the season of baseball’s Fall Classic, but it’s also a time for Wiffle ball tourneys galore. One that will be held later this month in Glendale, Ariz., bills itself as the World Series of Wiffle ball, as do a number of others around the country. Another just-finished tournament in the Northeast covered eight cities in six states. Teams in Texas are gearing up for a state championship. Two California tourneys are coming up in Costa Mesa and Ventura before the end of the year. Each year, more and more tournaments using patented Wiffle balls or similar orbs are being staged as the game’s popularity expands.

While the game has its roots in New England, California is well-represented. In one national ranking compiled by the Wiffle newsletter Fast Plastic, eight California teams are in the top 20.

“I never expected the game to evolve the way it has,” said Mike Palinczar, a Trenton, N.J., wiffler who helped pioneer serious adult play a decade ago. “Now there’s a tournament every single weekend.”

That may be an exaggeration, but not by much. Until recently, most people confined their play to the neighborhood or, at most, their hometowns. Now there are touring pros and cash prizes, though not enough for wiffleheads to give up their day jobs.

The reason given most often for the sport’s explosion in popularity is the Internet, which now boasts hundreds of Wiffle ball sites throughout the United States. Through the Web, people who thought they were unique in playing serious Wiffle ball began discovering they were not alone, giving the game a much broader base.

“It’s a strange underground cult, is what it is,” said Jay Wolfe, a devoted wiffler from Laguna Beach.

Though rules vary, the game of Wiffle ball is played by two teams, usually with three or four players a side. The field for tournament play is in the shape of a pie, with the batter standing at the narrow end.

Since there are no umpires, balls and strikes are determined by where the ball hits the backstop behind home plate. Strikeouts and fly outs retire the side. Lines mark off fair territory as well as the areas for singles, doubles, triples and homers. As play progresses, imaginary baserunners advance. Pitchers can grip the ball several ways, causing it to curve and dip much more than a regular baseball.

It is, in essence, a slightly more sophisticated game than the game played by millions of children over the years--and who still do. At the top level of play, it is dominated by men, most of whom played some kind of organized baseball as they were growing up.

So what’s the lure? Part of it is social, getting together on weekends with like-minded enthusiasts. But the other is the level of difficulty. Among the best of the wifflers, the perforated plastic ball can be hurled more than 75 mph from 45 feet away. That’s the equivalent of a major league 95 mph fastball, with the kind of movement sure to tie a hitter in knots. In Wiffle ball, even more than baseball, the edge belongs to the pitcher.

Take the case of San Diego’s Chris Hancock, only a few years removed from playing shortstop for the University of Denver. The rest of his teammates also played college baseball. Yet he thinks wiffling tests the limits of his hitting skills.

“It’s way more difficult to hit a Wiffle ball than a baseball, if it’s thrown by a good pitcher,” he said.

Or take the case of Ventura’s Chad Anderson, whose Wiffle ball team also is nationally ranked: “It’s a completely different game. No one in the majors can throw a drop ball like they do in Wiffle ball.”

More often than not, the Wiffle balls have been doctored big time. An unwritten rule is the more scuffed up the ball, the better, because the movement improves dramatically. New Jersey’s Palizczar, for instance, sells new balls for $13.99 a dozen. He sells scuffed “broken in balls” for $36 a dozen.

The Wiffle ball was invented in 1953 by a down-and-out resident of Fairfield, Conn., named David Mullany. His auto polish business had gone bust, and each day he set out to look for work.

As the story goes, Mullany came home one evening and noticed his son, also named David, trying to throw a curve ball using a plastic golf ball. A thought hit him that if he could invent a ball that curved naturally, he might have a marketable item. That evening, Mullany and his son sat at the kitchen table, cutting holes in white plastic balls with razor blades, looking for a combination that would produce the most action. The one that worked best had eight oblong holes on the top with a solid bottom. The Wiffle ball was born when Mullany asked his son the name of the game he played with his friends in the yard. To which the boy replied, “Wiffle. When you miss it, it’s a wiff.”

Mullany patented his invention, took out a second mortgage on his home to finance the venture and never looked back. Now, a third generation of Mullanys makes its living from Wiffle balls, manufacturing them in a small, unpretentious building in Shelton, Conn. David J. Mullany, a Wiffle vice president and grandson of the inventor (as well as the third David Mullany in this tale), said the ball has never been changed “because it works.” He also declined to divulge how many Wiffle balls the company has sold over the years, except to say “millions.”

“It’s pretty neat that people identify it with a good time growing up,” said Mullany. “It’s nice for us to see.”

The original bats for Wiffle ball were wooden, but they were soon replaced by the bright yellow plastic ones that are as ubiquitous as the ball itself. In recent years, technology and more serious play have caused a minor revolution in the bats, which are no larger than 2 inches in diameter. First came an aluminum version, then those made with space age carbon fiber began to appear, carrying a price tag of $120 or more.

Jared Lamph, a Long Beach orthotist who designed a line called Moonshot Bats, said the growing popularity of the new bats is simple: The level of play is getting so much better.

“It’s becoming such a competitive sport,” said Lamph, who uses only the Internet and word of mouth to market his bat. “Back East, it’s more structured and intense, but it’s getting that way out here.”

Still, as David J. Mullany put it, “It’s still a backyard kind of game.” More often than not, Wiffle ball is a child’s first introduction to baseball. And it is still used, even by pros, for training.

The San Diego Padre’s Tony Gwynn, one of the greatest hitters to play the game, uses Wiffle balls off a batting tee because he can tell from the spin where he struck the ball. Kevin Mitchell, in his day a much-feared pro slugger, said he learned to hit the curve by using Wiffle balls.

With the rising popularity of competitive Wiffle ball, the sport now has its own newsletter called Fast Plastic, and two portable stadiums--complete with fences and bleachers--now make the rounds of tournaments, mostly in the Midwest.

Newsletter publisher Billy Owens of Costa Mesa said there is no way to know exactly how many serious wifflers are out there because there is no umbrella organization.

“What we need is a major sponsor who would give us a decent amount of money to run a national program,” said Owens. “Then we wouldn’t have all these world championships.”

Back at Rick Messina’s place, one game is over and another has begun. Messina, a Long Island native, was sitting in the right field bleachers, watching the action on the field as well as a football game on a built-in television next to him. Most all the players who have shown up are stand-up comics and writers Messina has come to know from his years of managing comedians. He is more than happy to have them around.

“Rick just likes to hang out,” said John Caponera, a comedian who is coauthor of a yet-unsold screenplay about the weekly gathering.

Messina enjoys telling about his stadium, about how he and his pals used to play basketball regularly until they found themselves limping for several days after the game. When Messina moved to Encino several years ago, the Wiffle ball games began in the spacious backyard.

One thing led to another and before long a miniature version of New York’s Shea Stadium began to take shape. The bleachers, the dugout and the press box were built. Then, televisions were installed as were the instant-replay camera and sound-effects machine. The lights were put in for night games.

Then there were the coolers for beer, the bullpen, the Mets logo on the left field wall. Up went the outfield signs, some of them replicas of those at Shea (Newsday, Vienna Beef), others his own favorites (Grey Goose Vodka, The Drew Carey Show).

The stadium crept into the lot of the adjoining house, but no one minded. Then one day, the unthinkable happened. The house next door was put up for sale. Messina panicked, not knowing what new owners would think of his wiffle world. So he bought the house.

“It was overpriced,” said Messina in a deadpan.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.