A Promising Weapon in the Fight Against MS

- Share via

Before getting out of bed every morning, David Hassenpflug reaches for a pill--medication he calls “grease for the tin man”--so he can maneuver joints that have stiffened overnight.

Stiffness is typical for multiple sclerosis, a devastating disease that has left the 34-year-old Long Beach native in a wheelchair.

But Hassenpflug is feeling a little better these days. In June he participated in experimental therapy in which physicians attempted to rebuild his immune system using a stem cell transplant.

He’s still stiff, but his voice sounds less like he has marbles in his mouth, and a previously constant pain in his legs and hips is gone. He’ll probably never walk again, but his doctor said that, with physical therapy, Hassenpflug should gain strength over the next six months.

Early results from about 100 patients worldwide indicate that stem cell transplants--already used for treating cancers such as leukemia and Hodgkin’s disease--hold promise for combating MS. Researchers at Northwestern University also recently reported success using the procedure to treat seven patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, another autoimmune disease.

“We think it’s very exciting. To use a transplant designed to treat cancer for another disease is very satisfying,” said Dr. Stephen Forman, director of the division of hematology and bone marrow transplantation at City of Hope Cancer Center in Duarte.

Stem cell transplants fall far short of a cure. But published and anecdotal reports suggest that the procedure can halt the disease’s progression and, for some, lessen its severity.

“Right now, while it’s still experimental, it’s for patients who have had and failed conventional therapy,” said Dr. James Mason, program director for the blood and marrow transplantation program at Scripps Green Hospital in La Jolla.

But in the future, patients could undergo transplants before receiving other therapies and before they become seriously debilitated, he said.

An ailment with no cure, MS affects about one in 1,000 people. Medications such as interferon and copaxone can only slow, not stop, the downward physical spiral plaguing many. And treatments often do little to alleviate a plethora of conditions, from excruciating pain to muscle spasms.

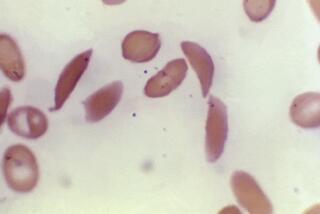

Like leukemia and Hodgkin’s disease, MS results from an immune system gone awry. The disease often strikes previously healthy people between ages 20 and 40, when the immune system begins aberrantly attacking a protective covering around neurons called myelin.

The attacks initially occur intermittently, causing temporary disabilities by short-circuiting electrical signals between the brain and the body. Repeated attacks eventually destroy the myelin, bringing some nerve transmission to a halt. Disabilities become permanent and ever-worsening.

Transplants attempt to stop the attacks by getting rid of the immune cells that attack myelin, Forman said.

In the treatment, physicians attempt to destroy the patient’s dysfunctional immune system with radiation and/or chemotherapeutic agents. They then inject healthy stem cells previously collected from the patient’s bloodstream, enabling him or her to form a new immune system. The hope is that the newly created immune system will be disease-free.

Because the stem cells are the patient’s own, immune-suppressing drugs are not necessary and the procedure is safer than using transplants from a donor.

The protocol for stem cell transplants varies. But generally, doctors begin by increasing the number of stem cells in the blood. A growth hormone pushes stem cells from the bone marrow, where they usually reside, into the bloodstream.

A simple blood collection system removes several pints of blood and runs it through a machine, separating the various blood cells by density. The stem cell layer is run over a column that recognizes a protein called CD34 on the stem cells’ surface.

To kill off the faulty immune system, patients receive chemotherapy, radiation or a combination of the two. Once the damaging cells are gone, the stem cells are injected into the blood, where they will generate a new immune system.

“Transplants wipe the slate clean,” Mason said. By resetting the immune system, doctors hope the therapy will suppress the indiscriminate attacks destroying nerves.

Even in the best-case scenario, the procedure is likely to have limitations, Forman said. It probably won’t repair nerves badly damaged by disease. However, so far, transplants appear to stop the immune system attacks and reduce the inflammation around nerves, improving function, he said.

With the disease stabilized and the inflammation reduced, patients’ mobility improves, enabling them to work on gaining strength, Mason said. “The muscle tone gets better. The balance gets better,” he said.

Though promising, transplants for MS are experimental, emphasized Dr. Richard Burt, director of allogeneic transplants at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago.

The largest study, published in the Journal of Clinical Immunology by Dr. Athanasios Fassas and his colleagues at George Papanicolaou General Hospital in Greece, showed that 70% of MS patients stabilized or improved after transplants. But that study involved only 23 subjects.

Some Doctors Remain Skeptical

No one knows how long the benefits will last. Debates rage over whether the environment or genetics triggers the disease. If genetic defects promote disease, then the MS may recur and doctors might weigh trying the riskier donor transplants. Large-scale clinical trials are needed to determine the efficacy and long-term benefits, Burt said.

Although such trials will not be done immediately, preliminary successes have induced the National Institutes of Health to begin moving in that direction. Burt and several other investigators will participate in a second-phase clinical trial of about 100 patients, scheduled to begin this fall.

Until the data come in, some doctors in the MS community said, they will remain skeptical about the new technique.

“The value really remains to be seen,” said Dr. Stanley van den Noort, a professor of neurology at UC Irvine and chief medical officer of the National Multiple Sclerosis Society in New York.

Patients can lead productive lives with a normal life span without taking such drastic measures, he said. Stem cell transplants put patients at high risk for infection for several weeks after the procedure, while they wait for the new immune system to develop, Van den Noort said, adding that about 5% die.

“It’s an interesting, but dangerous, approach, which carries rather more risk than I would like to accept for most of my patients,” he said.

But it’s a risk that Hassenpflug was willing to take.

Ten years ago, he was an avid athlete, obsessed with fishing, softball and playing guitar in a punk rock band.

Within a year and half, he could no longer walk. He lost more and more motor control, barely retaining his ability to feed himself. He developed extreme sensitivity to hot and cold. He suffered from involuntary muscle spasms in his legs. And he endured constant, severe pain in his legs, hips and lower back.

Without the transplant, Hassenpflug’s condition would have worsened. He most likely would have lost his already precarious hold on caring for himself, Mason said.

Now Hassenpflug says he notices improvement on a daily basis. “This is what’s going to stop the MS,” he said. “It’s got to.”

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

Interrupting the Cycle

More than 100 multiple sclerosis patients have been treated with an experimental procedure in which physicians attempted to destroy the patient’s dysfunctional immune system and create a new one that does not attack myelin, the insulation surrounding nerves.

*

1. Patient is given drugs to increase the number of stem cells, pushing them from the bone marrow into the bloodstream.

2. Several pints of blood are withdrawn from the patient. The stem cells in the blood are separated out with a special machine and the rest of the blood is returned to the patient.

3. The patient’s immune system is destroyed with radiation, chemotherapy or both.

4. The stem cells are then infused into the patient’s bloodstream, where they return to the marrow and begin producing new immune cells.

*

Sources: Dr. Stephen Forman, City of Hope Cancer Center; Dr. James Mason, Scripps Green Hospital; Dr. Richard Burt, Northwestern Memorial Hospital