Future Shock

- Share via

Baby boomers don’t like to admit they’re growing old.

Tweezers, rather than a cellular phone, is their most precious device because you can use it to pluck gray hairs and maintain the illusion of youth.

So understand my trepidation in deciding to watch Drew Saberhagen of Calabasas High pitch.

He’s my Kryptonite.

In covering high school sports for almost 25 years, I rarely felt fear until this assignment. But seeing Saberhagen forced me to face the obvious: I’m growing old.

It seems only yesterday Drew’s father, Bret, was pitching for Cleveland High.

I was at Dodger Stadium when Bret pitched a no-hitter against Palisades in the 1982 City Championship game. I remember seeing his parents argue in the parking lot over who would drive him to NBC studios in Burbank so he could appear on the 11 p.m. newscast with Stu Nahan.

He was a 19th-round draft choice of the Kansas City Royals and quickly signed a contract out of high school. I remember him working as a youth services coordinator at Cleveland, opening the gym to earn extra money. I remember attending his wedding at a church in Tarzana, where he married his high school sweetheart, Janeane. I walk past that church once a week.

In 1985, at 21, Saberhagen was the best pitcher in the American League. He won the first of his two Cy Young awards. Few will forget the 36-hour period when Janeane gave birth to their first child, Drew William, and the next day Bret beat the St. Louis Cardinals in the seventh game of the World Series, 11-0.

He was named World Series most valuable player and Drew became the most famous World Series baby ever.

So here I am going to see Drew pitch and feeling as if I’ve known him since birth.

Wasn’t it during the 1985 World Series that Royal fans were holding up signs, “Drew Saberhagen: World Series MVP 2005?”

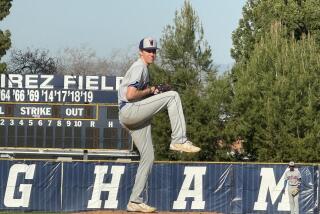

Drew is a 15-year-old freshman, 6 feet 1 and 155 pounds, throws left-handed and loves baseball like his father. He has a 3.5 grade-point average, which tells me he has his mother’s smarts because his father was never was very interested in school.

Drew realizes some people consider him a celebrity because he has a famous father. In Boston, where Bret is trying to come back from a second shoulder operation, Drew is asked for his autograph.

“It’s weird,” he said.

He has a similar reaction when watching videotapes of the ’85 World Series and hearing commentators talk about his impending birth.

Nothing fazes him. He understands the advantages and disadvantages he has inherited.

One advantage is people will pay attention whenever he pitches. A disadvantage is they’ll have unrealistic expectations, trying to compare him to a father, who will be a candidate for the Hall of Fame.

Drew is in no rush to become an adult overnight. He’s following the small, simple steps of his father.

At Calabasas, he’s one of two freshmen on the junior varsity. He’s 4-1 with a 0.80 earned-run average and is batting .457 with four triples in 12 games. He was a starting guard for the freshman basketball team and averaged 16 points.

He frequently talks with his father by phone and seeks advice.

“My grandma videotaped our first game and [my father] took it to the Boston pitching coach and he’s going to analyze it,” Drew said. “He wants me to be comfortable with what I’m doing.”

Several years ago, the Saberhagens endured an unpleasant, highly publicized divorce.

Thankfully, everyone has come out of it friends.

“All the legal stuff was rough on my parents, but both my parents are remarried and both my stepparents are great people,” Drew said. “If I ever want to go see my dad for a weekend, my mom would have no problem. They have nothing but respect for one another.”

His parents should be thrilled the way Drew is turning out. He’s dedicated to baseball but wants to have a life beyond a 15-second moment on television.

“The most important thing is to go out and win games and have some fun,” he said.

Rick Nathanson, Calabasas’ varsity coach, said of Drew: “He’s very unassuming but gifted. He really hasn’t even tapped into his potential as a pitcher. He’s a very gracious, humble kid who’s quietly driven to be as good as he wants.”

Drew isn’t the first son or daughter of a former high school athlete I’ve covered, and he won’t be the last. But he gave me a scare, for he’s a reminder how quickly time passes and how life repeats itself.

Seeing him pitch wasn’t depressing--it was exciting. There’s another Saberhagen ready to earn respect on his own terms.

There are others on the way.

The 6-year-old daughter of Samantha Ford, former Hart softball sensation, is getting ready to become a golfer and pitcher.

Fox Jantz, a football player at Kennedy in the 1980s, has three sons--Truk, 12, Steele, 11, and Brogan, 10. They’re baseball and football standouts.

James Bonds, 8-year-old son of former Hart and UCLA quarterback Jim Bonds, is showing a strong arm like his father.

Bernie Forbes, a third baseman for Granada Hills’ 1978 City Championship team, has an 11-year-old son, Travis, who hit 19 home runs in 20 games last year.

Bring ‘em on. Let me write about them. We’ll see if the next generation learned anything from their parents, especially about being kind to old sportswriters.

*

Eric Sondheimer’s column appears Wednesday and Sunday. He can be reached at (818) 772-3422 or eric.sondheimer@latimes.com.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.