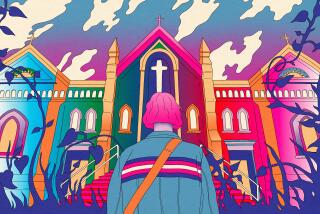

Church Welcomes an Atheist as Teacher

- Share via

Stuart Bechman-Besamo hasn’t believed in God for years. Yet here he is, spending most Sundays at the Simi Valley United Church of Christ, teaching the parish’s young people about religion.

An atheist at Sunday school may seem like a wolf in sheep’s clothing or the setup to a bad joke. But Bechman-Besamo is not here to persuade his teenage charges to abandon their church. He is here to challenge them, to encourage tolerance and perhaps, church leaders hope, to bolster the faith of others.

Only an open-minded church would attract a couple like Bechman-Besamo, who left the Methodist church in high school, and his wife, Jeanie Mortensen-Besamo, an ex-Mormon. The 100-member congregation, formed in a 1994 merger of two churches, proclaims in its mission statement: “For us the Bible is a record of faith journeys to be taken seriously, but not always literally. . . . Our church seeks to be multicultural, respecting and learning from traditions which differ from our own.”

Stuart and Jeanie first encountered the Simi Valley church in early 2000, while working with its members to fight Proposition 22, a successful ballot measure aimed at banning recognition of same-sex marriage in California. (The couple added the word “Besamo”--a combination of their and Jeanie’s daughter’s last names--to their surnames when they married two years ago.)

After leaving Mormonism, Jeanie was looking for a more inclusive place to worship. She joined the Simi Valley church and volunteered to help with its youth program. She thought that teaching kids about religion would be something she’d handle by herself--until two members of the church’s youth group announced a year ago that they were atheists.

Church leaders decided that to take this declaration seriously, they needed to introduce the youth group to an atheist. They thought of Stuart.

“Stuart,” said the church’s pastor, the Rev. Bill Greene, “is a caring, bright, perceptive, inclusive kind of person who has a strong sense of justice. . . . We are not starting an agnostic club. It’s just that here is this incredibly fine man, with honesty and passion for justice, who is in our church. And that’s a blessing for us, and for all of our kids.”

Which is why the atheist can be found Sundays in the church’s “clubhouse”--a converted garage whose closet still holds a lawn mower--less than 100 yards from the church’s cozy sanctuary.

Stuart, 41, said he began calling himself an atheist 15 years ago. More recent readings and discussions “have served only to bolster my stance of nonreligious belief,” he said.

He agreed to participate in Sunday school in part because he wanted to “teach tolerance for people like me.”

“If they know a person who is an atheist,” he said, “they won’t have any negative preconceptions about atheism. If they find their beliefs head that way, they won’t feel like an outcast, that something is wrong with them. I consider this process similar to what gay individuals go through.”

On a recent Sunday, Stuart leaned against the edge of a heavy oak table at one end of the clubhouse, engaged in a sort of Socratic dialogue with teenagers. “Can anyone tell me what the Christian view of sin is?” he asked.

The four students in attendance, sprawled out on the mismatched chairs and couches that make up most of the clubhouse’s furniture, shouted out answers: Infidelity. Stealing. Lying.

Standing next to her husband, Jeanie wrote the teenagers’ answers on a white board, trying to squeeze all the ink she could out of a dry-erase marker that would not cooperate. She let Stuart ask the questions and then added to the discussion, drawing on her own background and readings to create a fuller picture of the Christian doctrines on sin and grace.

Stuart pressed on. What makes a sin in Judaism, Islam, Hinduism? The students offered some examples: killing someone, maybe, or swearing. Not praying as often as your religion tells you that you must. And then Steven Smitha, 14, bolted from his chair, hand pointed in the air.

“Sin,” he yelled at Stuart, standing two feet from him, “is McDonald’s in Hinduism!”

Sunday school class can take on a wacky tone when so many perspectives get tossed around so freely. Stuart tried, somewhat unsuccessfully, to guide the conversation back to religion. “What does sin mean to a humanist?” he asked. In Stuart’s vocabulary, the words “humanist” and “atheist” are largely interchangeable.

“A personal sense of right and wrong?” wondered Randy Torrey, 17, a senior at Thousand Oaks High.

“What Jiminy Cricket tells you not to do,” Steven added. The room erupted in laughter.

Stuart rolled his eyes. He and Jeanie tolerate this controlled mayhem because they believe that the discussion stimulates the curiosity of their students about different religions, helping the teenagers articulate what they like, and dislike, about organized religion.

Matt Smitha, 16, said that what he learns at Sunday school is beneficial for his regular high school experience, as a junior at Buena High in Ventura. “I have friends at school who are of different faiths; it’s helped me understand a little better where they are coming from.”

Said Jeanie: “We have a church here with differing viewpoints, and we want the kids to know that there are organizations and churches that don’t insist you conform to a certain way.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.