Egyptians’ Obsession With Grades Fails to Nurture Creative Thinkers

- Share via

CAIRO — The school day is over and thousands of secondary students here rush home, laden with books. But it isn’t the prospect of television or socializing with friends that drives the stampede.

Instead, the students want to spend time with their textbooks, in hopes of absorbing even more science, history and philosophy than they learned at school. Often, teachers come to their homes as tutors hired by anxious parents.

On its face, such devotion to learning might seem a welcome prospect to American parents who struggle to get children to study amid a dizzying array of entertainment options.

But in this city of about 10 million people, it’s a symptom of an educational crisis that threatens the fabric of Egyptian society.

Critics complain that the public education system begun under the Egyptian monarchy nearly eight decades ago has become little more than a contest to see how well students do on national exams.

Even universities churn out graduates who are often unprepared for the rapidly evolving technology in the marketplace, given the emphasis on rote learning rather than creative thinking, said Cairo University economics professor Mona Baradei.

“The value of education has become a source of jokes,” added sociologist Madeha Safty, who teaches at the American University in Cairo.

In the public school system, test scores determine not only if a student will go to college but also what career he or she can pursue. To study engineering or medicine, for example, students must score more than 90% on the national test given at the end of 11th grade, the senior year for college-bound Egyptians.

National exams also determine whether students are promoted to the next grade under the centralized education system. Nothing else is taken into account to evaluate a student’s ability--not extracurricular activities, teacher assessments or classroom performance.

Some academicians have dubbed the Egyptian obsession with national scores “diploma disease,” one shared by several African and Middle Eastern countries.

It’s a tradition that the government has had a difficult time breaking, said Hamed Ammar, an education professor who serves on an official committee promoting school reform. The slightest change to a test question, for example, generates widespread parental complaints, he said.

“Here, if a student gets a high score, it’s a neighborhood event,” said Russanne Hozayin, a testing manager for the U.S. Agency for International Development, which is helping Egyptian educators improve the teaching of English.

But high test scores don’t translate into learning to think, Safty said; instead, students repeat facts they have memorized.

Most of the incoming freshmen she encounters must be taught how to develop reasoned responses based on their understanding, rather than simply to regurgitate what she puts on the blackboard, Safty said.

Hoda Mohammed, a 16-year-old secondary school student, agreed. However, she argued that students have no choice but to memorize, given rigid testing methods that don’t allow for creative answers.

Teachers, meanwhile, have turned the demand for tutors into profit, charging fees that can amount to a quarter or more of some families’ monthly incomes, according to the government’s National Institute of Planning.

Ali Mohammed, a senior who is no relation to Hoda Mohammed, said his father is a judge and can afford the $40 a month to hire tutors for six hours a week. “It would be difficult to do well without them,” the 17-year-old said of the tutors.

But a mother of 11- and 13-year-old girls, who asked not to be identified for fear that her daughters’ academic standing would be jeopardized, said she refuses to pay the exorbitant charge.

The costly tutoring was once unheard of in a nation where public education has been prized as a resource accessible to rich and poor since the 1952 revolution. It was then that the government established a compulsory and free six-year primary school system.

These days, the media carry stories of families struggling to pay rising fees for private lessons to bolster performance on exams.

Rising costs also have raised the illiteracy rate, Baradei wrote in a report last March. According to the most recent UNICEF statistics, only 64% of men and 38% of women in Egypt can read.

“Free education at all levels has become a false entitlement, especially for the poor,” Baradei wrote. “This is mainly due to the emergence and spread of private tutoring,” along with rising costs such as user fees and school supplies.

Some tutors charge as much as $60 a week, or about $2,400 for the school term, critics say. The average teacher earns only about one-fourth that amount in the classroom.

Less expensive after-school lessons recently begun by the Education Ministry have barely helped, Baradei said.

Other reform-minded educators insist that teachers are not the only ones at fault.

“What if all teachers who give private lessons in Egypt would stop giving lessons? The students would go elsewhere,” said Yasser Youssif, who trains teachers for the Education Ministry, adding that tutoring is a necessity under the current system because teachers don’t have time to review much of what students are expected to memorize.

He and other critics argue that unqualified teachers and restrictions over how courses are taught contribute to poor learning.

Strict control over curriculum, down to the tools used for each day’s lessons, has been going on for decades, said professor Ammar. He recalled how he almost lost his first teaching job in Upper Egypt in the late ‘50s.

To teach about the Nile, Ammar had students build an outdoor model of the river with sand and a water hose. The children were mesmerized, he recalled, floating little boats on the makeshift river and asking lots of questions.

They absorbed the material far better than they would have if they had gazed at a map on the wall while Ammar lectured, as called for by the geography lesson.

“Unfortunately, the inspector came to visit the school while we were outside,” he said. “They called me to the headmaster’s office, where I was threatened that I would be fired if I ever did that again.”

Punishment for teachers who deviate even slightly from the lesson plan continues, he added.

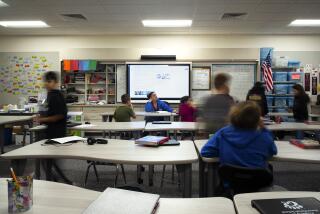

The condition and shortage of school buildings also impair education, critics said. The facilities here in the capital often have broken windows, overflowing toilets and few, if any, amenities such as laboratories, say students and teachers. Many classrooms pack in 60 or more students at a time.

Schools in the countryside also are in poor shape. There are not enough classrooms for a student population that grows by 108,000 nationwide every year, Ammar said.

Even a zealous program launched recently to build 2,000 schools a year during the next decade is not likely to meet the burgeoning demand, he said: “We have 36,000 schools, but we need another 36,000 schools.”

The poor quality of schools, teachers and curriculum has led to a dropout rate of as much as 50%, mostly among poor children, Baradei said. “Parents soon discover that the financial return of . . . education is very low,” she said. “After eight years of spending on this child’s basic education, he will earn nothing in terms of wages.”

By comparison, “if a 9- or 10-year-old works at a workshop with a mechanic or craftsman, he will make a lot of money to help his parents with,” she said.

But reformers say they won’t give up on trying to fix Egypt’s educational woes. Last month, Ammar’s committee proposed that 10% of the national exam questions should test creative thought.

Similar proposals failed in the past because of public pressure to keep the status quo, he added.

*

Times researcher Aline Kazandjian in Cairo contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.