Rights Panel Finds Fla. Vote ‘Injustice’

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Disenfranchisement of Florida’s voters in November “fell most harshly on the shoulders of African Americans” in a presidential election marked by “injustice, ineptitude and inefficiency,” according to a draft report by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights.

The confidential report by the independent federal agency repeatedly urges the U.S. Justice Department and Florida’s attorney general to immediately investigate whether Florida officials violated state or U.S. law by employing policies and practices that unfairly harmed minority voters.

“Despite the closeness of the election, it was widespread voter disenfranchisement, not the dead-heat contest, that was the extraordinary feature in the Florida election,” according to the 197-page document, key portions of which were obtained by The Times.

“The disenfranchisement was not isolated or episodic,” it adds. “State officials failed to fulfill their duties in a manner that would prevent this disenfranchisement.”

African American voters were nearly 10 times more likely than white voters to have had their ballots rejected in Florida, the report states. Of the 100 precincts in the state with the highest number of disqualified ballots, 83 are majority black. Overall, 54% of the ballots disqualified were cast by black voters, the report says.

The draft report says investigators found no “conclusive evidence” that state officials conspired to disenfranchise blacks or anyone else in Florida. Nor will it affect President Bush’s 537-vote statewide margin of victory over Al Gore, which gave him the White House.

But the panel sharply criticizes the president’s brother, Florida Gov. Jeb Bush, Secretary of State Katherine Harris and other Florida officials for neglecting widespread weaknesses in the voting system and failing to prepare for increased voter turnout. In testimony before the commission, Bush and Harris argued that their powers were limited under the state’s constitution and denied any wrongdoing.

The advisory commission has no power to enforce its findings, which the panel will consider at a meeting Friday. But ever since Congress created the panel as an independent agency in 1957, its reports on major racial conflicts and controversies have helped mold public opinion and guide government action.

Both the Justice Department and the state attorney general’s office launched investigations into possible civil rights violations after the election. No results have been announced and it wasn’t immediately clear if the commission’s recommendations would lead to wider inquiries. The commission consists of four Democrats, three independents and one Republican.

Even unintentional acts that have a disparate effect on minority voters are illegal under a 1982 amendment to the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The draft report focuses heavily on the now-familiar litany of problems that bedeviled Florida’s voters: error-prone punch-card ballots, confusing ballot designs, unreliable voting machines, inadequate resources and a botched effort to cut felons from voter rolls that mistakenly disenfranchised legitimate voters.

According to the report, the data on the computerized felon list had “at least a 14.1% error rate.” The state’s use of the list, combined with a state law that forced voters to get themselves off the list, “resulted in denying countless African Americans the right to vote.”

Florida’s Legislature approved sweeping election reforms in early May in an effort to correct many of those problems, so the effect of the commission report and its recommendations may be limited.

The Legislature voted to eliminate punch-cards, paper ballots, mechanical lever machines and counting systems that contributed to high error rates, for example. They also agreed to allow “provisional ballots” for voters who are challenged at the polls, and provided money to train poll workers.

The civil rights panel plans to return to Florida next year to monitor the reforms before the state’s 2002 gubernatorial elections. “The commission is quite accustomed to legislatures passing laws and then never doing anything,” the commission chairwoman, Mary Frances Berry, said in a recent interview.

Commission hearings in Tallahassee and Miami earlier this year focused on election irregularities. Panel members quizzed more than 100 witnesses as they sought to determine who made critical decisions and how they affected minority communities. At issue: why 180,000 presidential ballots were disqualified and not counted last fall.

Florida saw a record black turnout last year thanks to registration and get-out-the-vote drives by unions, students and other groups. About 893,000 African Americans went to polls across the state, a 65% increase from 1996.

“If it was a systematic plan” to discourage black voters, “it failed,” said Darryl Paulson, political science professor at the University of South Florida.

But the huge turnout caused huge problems. State and county officials did little or nothing to ensure that affected precincts were adequately prepared, creating long lines and jammed phones. And no one taught the new voters how to cast ballots.

“We didn’t do any voter education,” said Isiah Rumlin, head of the National Assn. for the Advancement of Colored People in Duval County, which consists of Jacksonville and its environs. “We didn’t know we needed to. . . . In retrospect, we should have done a better job.”

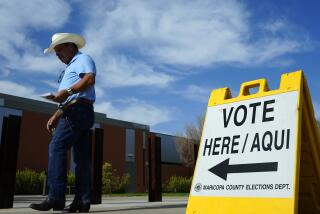

The civil rights commission also investigated widely circulated reports that Florida police stopped and intimidated vast numbers of black voters near polling places across the state.

In reality, the Florida Highway Patrol ran three roadblocks that day--in Leon, Escambia and Bay counties--to check licenses, registration and safety equipment. Troopers erect similar posts almost every day across the state.

The Leon County checkpoint was unauthorized, however, because troopers hadn’t obtained proper approval. Col. Charles Hall, head of the highway patrol, said about 150 cars were stopped at midmorning more than 2 miles from the nearest polling station. Six of the 16 drivers who were issued traffic tickets or warnings were non-white, he added.

“No member of the community was unreasonably delayed or prohibited from visiting their voting precinct” because of a checkpoint, Hall said.

But Bob Butterworth, Florida’s attorney general, called the checkpoints “inexcusable” and “flat-out wrong,” even though an investigation by his office found no evidence that voters were intimidated.

“It was absolutely not necessary for law enforcement purposes, and similar checkpoints should never again be implemented on election day,” Butterworth said.

Far more important than roadblocks were confusing ballot designs and the failure of many counties to use so-called “second chance” technology: counting machines that reject ballots with double votes and other errors so the voter can cast another ballot.

To be sure, white voters were also affected by such problems. Thousands of white retirees complained about the confusing “butterfly” ballot in Palm Beach County, for example, and spoiled their votes. But heavily black precincts there had far higher error rates.

Duval County also had a ballot that was a design disaster. Gore, Bush, Ralph Nader and two other candidates were on one page. Five other candidates were on another page. Even worse, the official sample ballot printed in local newspapers before the election instructed voters to “vote all pages.” Anyone who did so spoiled their vote.

“If you read the instructions on the sample ballot, you would have voted wrong,” complained Rep. Corrine Brown (D-Fla.).

About 16,500 ballots were rejected as double-votes in the county’s four black-majority districts. About 4,500 ballots were tossed out in the 10 mostly white districts. Put another way, 1 in 5 ballots was tossed out in black districts compared to 1 in 20 in white areas.

Experts blame several factors, including lower literacy rates among minorities and a reluctance to challenge officials in a state where violent racial attacks once were common and voting rights were sharply curtailed.

Whatever the cause, the state’s voting process is “systematically biased” against minorities, argued Lance deHaven-Smith, assistant director of the Florida Institute of Government at Florida State University in Tallahassee. “Is it intentional? Obviously not. Unless we don’t fix it now that we know it’s a problem.”

The election was widely discussed at a recent legal clinic in the NAACP office in northern Jacksonville, a dimly lit room behind a heavily barred door in a dingy roadside shopping center.

A videotape documentary about Florida’s bloody civil rights battles played in one corner, while wall posters bore grisly details of scores of 19th and early 20th century lynchings. Two dozen people waited patiently for a chance to talk to a lawyer.

Some said they were stymied by hostile poll workers who wrongly demanded multiple photo IDs, even though state law only requires one.

Others said that some polling stations closed at 7 p.m., turning away those already in line, or changed locations without notice.

“You had to go all over town to find out where you were supposed to vote,” charged the Rev. James B. Sampson, pastor of the First New Zion Missionary Baptist Church.

Still others said they voted--but now fear it wasn’t counted.

“I was so confused,” admitted Emory Kinsey, 45, a public works driver. “I don’t even know if I voted for the right person or not.”

Off on the side, L. Ross Davis, a fiery NAACP organizer, boiled with fury. He helped register 3,228 new voters in churches, schools, malls and slums. He is convinced of a conspiracy to disenfranchise blacks. And he is determined not to let it happen again.

“Yeah, I’m mad . . . ,” Davis said, “mad that someone would pollute a system that was pure. But we won’t be fooled again. We’ll redouble our efforts next time. That I promise you.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.