A CASE OF THE BLAHS

- Share via

When the National Football League merged with the American Football League in the late 1960s, and the NFL thereupon devolved into the National Football Conference and the American Football Conference, three NFL teams agreed to join the AFC.

Pittsburgh. Cleveland. And . . .

And--and, um, what was the other one? Neil Austrian, who served as NFL president during the 1990s, could not remember. Sitting on the witness stand a few days ago in Los Angeles Superior Court, the name of the third team just would not come to him.

“Baltimore,” said Oakland Raider owner Al Davis, sitting in the courtroom audience, speaking so softly that even those closest to him could barely hear the word.

A few moments passed. Still Austrian could not remember. “Baltimore,” Davis said, this time much louder, his voice booming around the courtroom.

Everyone turned, even the judge--to look at the other man in the room dressed in black, the one suddenly testifying from the gallery, the man whose gift for commanding a stage dominates the proceedings in the Raiders’ billion-dollar lawsuit against the league. Jurors nodded and smiled.

Three weeks into the case, the evidence is abundantly clear that Davis is the undisputed star of the trial and the Raiders the team to beat when it comes to theater and emotion.

And a trial, as any seasoned lawyer will tell you, is as much about theater and emotion as it is about facts--particularly in a case like the Raiders versus the NFL, which is essentially a complicated business dispute, not unlike a fight over where a widget factory ought to be located.

“Emotion plays a huge part in any trial,” said Kevin A. Duffis, a Santa Ana attorney and actor who used to have a recurring role on the TV show “L.A. Law.”

“Oftentimes lawyers go to law school thinking they can win the day with linear logic. Honestly, most jurors do not decide that way. They’re very intuitive,” Duffis said, adding, “They don’t wade through a case going, ‘A-B-C-D-E.’ By the time they get to B, they’ve formed general impressions of a case and what they think is just.

“They form opinions the first time you walk into the courtroom--whether they like you, whether you dress nicely, whether they think you’re intelligent. They make intuitive decisions about how credible you are, early on.

“If,” Duffis said, “you can win them over in the first quarter, so to speak, the game is yours.”

The trial is due to run until early May. Replace “widget factory” with “football franchise” and you get the essence of the case. The Raiders say the NFL interfered in 1995 with their plan to build a $250-million stadium at Hollywood Park, leaving Davis with no option but to return to Oakland after 13 seasons in L.A. The team also claims it still owns the Los Angeles market for NFL football. It is seeking more than $1 billion in damages. The NFL denies any wrongdoing.

Already, the trial has featured long stretches of the sort of testimony that would make the prospect of watching an XFL game seem inviting. Witness a discussion about the meaning of the acronym “EBITDA”--meaning “earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization.”

Or skirmishes between the Raiders’ lead attorney, Joseph M. Alioto, and NFL Commissioner Paul Tagliabue over the meaning of the word “concept” and the utility of quotation marks around the phrase “fresh start” in a league-issued memorandum--for emphasis, as Alioto suggested, or to indicate a colloquialism, as Tagliabue said.

And then there was an exchange that has to rank as one of the more inspired in American jurisprudence.

Alioto, speaking to Tagliabue, referred to a prior question that included the phrase “et cetera, et cetera.”

Tagliabue said, “I think it was, ‘Blah, blah.’ ”

No, Alioto replied, “There was a ‘blah, blah’ before that one.”

So much tedium. And so much more for jurors to endure.

All of which makes the role of emotion--and that of star quality--that much more important. It also highlights the contrast between Davis--who has yet to testify, at least from the witness stand--and Tagliabue, who was called to the stand by the team but served as the league’s principal witness.

Each morning, shortly before testimony begins at 9:30, Davis sits himself down in the first seat in the first row of the gallery. When the proceedings break, the jurors file past him to leave the courtroom.

No one else has sat in what quickly was established as Davis’ seat. No one has dared try.

Anyone who wants to can observe Davis’ 1984 Super Bowl ring, the one the Raiders won when they were in L.A. It’s on his left hand. There’s a diamond-crusted pinky ring on his right hand.

Each day Davis dresses in a black suit. Sometimes he wears a black shirt. Sometimes a silver one. His ties are silver or black or white. Anyone who has spent any time watching the trial is invariably asked what Davis--who prefers leather jackets or Raider-emblazoned sweatsuits--is wearing, which he said he finds bewildering and fascinating.

“I wear a lot of leather, a lot of club jackets,” Davis said. “But I can wear a suit and a tie when I have to.”

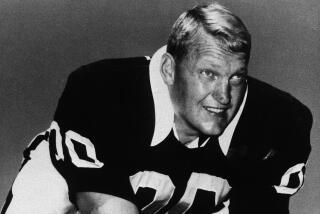

From his perch, Davis watches, laughs (quietly), shakes his head, fulminates, ruminates, writes notes. When Carolina Panther owner Jerry Richardson took the stand, Davis nodded at him before the testimony began--a coach acknowledging a former player. Davis once coached Richardson, who in the late 1950s was an NFL wide receiver.

During breaks in the proceedings, Davis, Alioto and others involved in the case on behalf of the team gather outside the courtroom on the sixth floor of the downtown L.A. courthouse. When the huddle breaks up, it’s not uncommon for an autograph hound or two to shyly approach Davis. Well-wishers--among them Ron Mix, who like Davis is an NFL Hall of Famer and who now is a lawyer living in San Diego--have stopped by to give their regards to Davis, invariably referring to him as “Coach.”

With the exception of solicitous PR men Joe Browne and Dan Masonson, the NFL has often abandoned this out-of-court platform to the Raiders. During breaks, the NFL’s attorneys--folksy San Jose lawyer Allen Ruby, backed up by the powerhouse New York-based law firm of Skadden, Arps--typically retire to the fifth floor of the courthouse to plot strategy.

Tagliabue, in particular, did not linger on the sixth floor to trade off-the-record observations with reporters or check out the scene--as Davis does. During his six days on the witness stand, he was directed by league attorneys not to speak with reporters about the case.

Tagliabue showed up for court dressed usually in gray. He squinted at the overhead projector set up in the middle of the courtroom, looking less like one of the most powerful people in professional sports and more like a high school chemistry teacher assaying the properties of helium. He told jurors the squinting was an astigmatism problem. He used the word “unagreed.” An East Coast guy--he’s a native of New Jersey--Tagliabue pronounced it “Los Ange-leeze.”

In court, Davis frequently reacted to Tagliabue’s testimony. Outside court, in a comment he said could be used on the record, Davis called Tagliabue’s testimony a “raft of lies.”

Last Wednesday, at the end of his sixth day in court, Tagliabue was clearly itching to leave--wanting to go back to his home and also to check in at league offices in New York before returning to California for the NFL’s annual meetings earlier this week in Palm Desert. Alioto kept him on the stand until 3 in the afternoon. The commissioner had to slog to the airport in rush-hour traffic.

For his part, Tagliabue was cool on the stand, never raising his voice in response to Alioto’s baiting, biting questions.

Wedged into the witness stand, his back to Judge Richard C. Hubbell, turned so that in responding to questions he was speaking directly to jurors, Tagliabue parsed his words and delivered them in a calm, measured monotone.

“And who,” Alioto asked at one point, referring to a meeting about the Hollywood Park proposal, “was there for the Raiders?”

Tagliabue delivered a classic legalism that brought to mind for some a certain ex-president. “It depends on what ‘there’ means,” he said.

Tagliabue, formerly the league’s lawyer, played a role in the first round of litigation between the Raiders and the NFL, the antitrust case in the 1980s won by the Raiders and Alioto’s father, Joseph L. Alioto, the former mayor of San Francisco. That litigation paved the way for the Raiders’ move to Los Angeles and, the team claims, an animus directed at the team and at Davis.

A key theme of the Raider case is that the league is out to get the Raiders. The league denies anything of the sort.

The Raiders’ Exhibit A on this point is a June 2, 1995, letter to Tagliabue from Wellington Mara of the New York Giants, which refers to a “long list of Raider atrocities.”

During his time on the stand, Tagliabue called Mara the “conscience of the league,” at least “in some respects.” But Tagliabue also strongly denied that he personally bears Davis any ill will or that the league sabotaged the Hollywood Park deal. Tagliabue stressed that the league, which wants a state-of-the-art stadium in Los Angeles so it can stage Super Bowls here, worked hard to try to make the Hollywood Park deal happen.

Addressing news crews earlier this week at the league meetings in Palm Springs, Tagliabue also made plain a feeling--carefully not pinning it on anyone in particular--circulating within the league.

“I think most of the owners regard the case as a sham or a counterfeit,” Tagliabue said. “Some of them regard it as a shakedown.”

In court, meantime, Tagliabue offered an observation about NFL football that may, at the conclusion of the case, also serve to underscore the way juries and trials operate.

“Our sport is about connection, passion, loyalty”--at that, Davis laughed in his front-row seat--”identification with heroes . . . and emotion,” Tagliabue said. “Once you trifle with those emotions and loyalties, you turn off a certain number of fans.

“And,” Tagliabue said, “it’s tough to get them back.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.