Trial Opens in Sotheby’s Price-Fixing Case

- Share via

NEW YORK — Some of the conspiracy allegedly was carried out in a limousine and a 5th Avenue apartment, but the dynamics are the same as those you might see at any garden-variety criminal trial: The prosecutors made deals with underlings and co-conspirators to catch the bigger fish; and the bigger fish’s attorneys now are accusing the littler ones of lying to save their own skins.

Of course, even the little fish are hardly guppies at the trial of A. Alfred Taubman, the 76-year-old former chairman of Sotheby’s auction house, who is accused of plotting with the head of rival Christie’s to fix commissions in the $4-billion auction industry.

The chief witness against Taubman will be his onetime protege, Diana D. Brooks, the former CEO of Sotheby’s and former Yale trustee who wielded the gavel at the firm’s glitzy Manhattan auctions before pleading guilty last year to conspiring to violate antitrust laws. Also on the government’s witness list is Christopher M. Davidge, the onetime chief executive of Christie’s, who admits secretly meeting with Brooks--once in her limo at Kennedy International Airport--to make sure the two dominant auction houses did not undercut each other in taking their commissions from the sellers of Renoirs, Picassos and other fine art, antiques and jewelry.

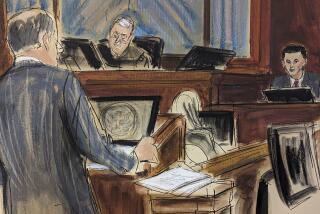

In opening statements Friday in what is expected to be a month-long trial in U.S. District Court here, Justice Department anti-trust prosecutor John Greene told jurors who likely had never been close to a Sotheby’s or Christie’s auction that “this is a simple price-fixing case.”

But after giving the panel a primer in the basics of auctions, Greene reminded them that this was no simple cast of characters, describing how Taubman “got in his private jet and hustled over to London” to see his counterpart at Christie’s in 1993 when both of the historic auction houses were suffering from slumping art prices that drove down their return on sales. After other “private one-on-one-meetings” in London and at Taubman’s 5th Avenue home, “ladies and gentlemen, the price fix was in,” he said.

Greene had to acknowledge, however, that he will face the same challenge as prosecutors in many criminal trials, having to depend on the testimony of “people who were actually involved in illegal activity.”

That set the stage for defense attorney Robert B. Fiske Jr. to deride the government’s star witnesses as the real perpetrators trying to point the finger elsewhere to stay out of jail, in Brooks’ case, and to profit, in the case of Davidge, who is collecting an $8-million severance package from his firm.

“There was a crime here--it was committed by the two principal witnesses,” Fiske said.

He described Taubman, in contrast, as a self-made man who began working at age 9 and became a philanthropist so rich--with a net worth of more than $700 million--that he had no need for such conspiracies. His aging client also “has a little bit of a hearing problem,” Fiske said, explaining why Taubman was wearing headphones as he sat at the end of the defense table.

The trial is the only one stemming from a four-year-old federal investigation into practices in the high-end auction business dominated by the two British firms that date back to the 18th century. The price-fixing scandal has shaken an auction world that long thrived on an image of society manners, even while the firms tried to wrangle the rights to sell the holdings of leading collectors and created party-like atmospheres at the auctions to encourage bids to rise, sometimes at $1 million a pop.

The investigation appeared to be going nowhere until Christie’s CEO Davidge resigned the day before Christmas 1999. A month later it was revealed why: Christie’s was cooperating with the Justice Department in return for “conditional amnesty,” a status granted suspects who report “illegal activity . . . with candor.”

The fallout continued even after both Brooks and Taubman resigned their posts at rival Sotheby’s. In a civil case here, the two auction houses agreed last year to pay $512 million to settle a class-action suit filed by their former clients. Taubman agreed to pay $186 million of Sotheby’s share.

Sotheby’s and Brooks each then pleaded guilty to one criminal count, with Brooks admitting she had conspired for more than six years with Christie’s to “suppress and eliminate competition.”

Setting the stage for the current courtroom showdown of two of the biggest names in the auction world, she also said she was acting “at the direction of a superior.” The only person who met that description was Taubman.

Though Taubman admitted his civil liability for the price-fixing by his firm, he vowed from the start to fight the criminal charges, saying he was “absolutely innocent” and blaming the woman who had day-to-day control over the auction house he bought in 1983. “Whatever Ms. Brooks chose to do, she did completely on her own--without my knowledge or approval,” said Taubman, who remains the largest shareholder in Sotheby’s.

The trial before U.S. District Judge George B. Daniels will hinge largely on whether the jury buys that contention. That was why Taubman’s lawyer on Friday began painting a portrait of Brooks as an iron-willed chief executive who boasted that “this was 100% her show” and relished her “celebrity status.”

Fiske told the jury that Brooks kept no notes and changed her story over time so prosecutors would help her avoid a potential three-year prison sentence.

Though the trial only alleges a conspiracy to fix sellers’ commissions, the Justice Department has accused the two auction houses of colluding in a series of ways. Until 1993, for instance, winning bidders paid a flat 10% surcharge to both auction houses above the final hammer price. But within weeks of each other that year, the two firms adopted a sliding scale that increased their take, getting 15% on the first $50,000 and 10% for amounts above that.

The auction houses also allegedly agreed to stop offering cut-rate deals to certain elite art owners, and then shared lists of those with whom such deals were already in place so those could remain in effect under a grandfathered arrangement.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.