Ellison’s ‘Invisible’ Still Walk Among Us

- Share via

“I am an invisible man.” So begins the most important book on American race relations since “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man,” published 50 years ago today, portrays an unnamed black character as he struggles to make a name for himself in an America that refuses to “see” him. “When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves or figments of their imagination--indeed, everything and anything except me.”

Today, an important task of American politics is to make room for black Americans to be “seen” and judged as individuals. With April marking 10 years since riots broke out in Los Angeles after four police officers were acquitted in the beating of Rodney King, we would do well to consider what remains to be done politically and socially to bridge the increasing racial divide in the nation.

Ellison emphatically denied that black Americans were merely the sum total of their experiences with slavery and segregation. Constrained by racial prejudice in law and custom, they also were participants in what Ellison called a “broader American cultural freedom” that reposed a responsibility in each citizen to think and act.

“But what kind of society,” the invisible man asks, “would make him see me?”

The tragic irony for black Americans is that they suffer from both visibility and invisibility. Their “high visibility” as blacks living in a predominantly white society makes them the legal and social target of racism, while their individuality remains invisible to a white society that judges them only by their color.

In 1966, Ellison testified at a Senate hearing on U.S. cities. Instead of the government treating black Americans “as though we are being legislated for rather than with,” Ellison suggested that laws “should grant to each Negro his individuality.” This would help the diverse individuals within the U.S. “know one another without the myths of racial inferiority or superiority.”

This also created “a fair field of testing.” As Ellison said, “I don’t expect any special provisions to be made for me because I’m a Negro.” No literary condescension; no legal condescension.

In this he channeled the muse of Frederick Douglass, who believed that the so-called “Negro problem” would disappear as soon as the government stopped treating black Americans differently from white Americans.

When Ellison received the National Book Award for “Invisible Man,” he said that he modeled his effort after an earlier generation of American writers who “took a much greater responsibility for the condition of democracy.” Like Melville and Twain, Ellison wrote as an appreciative critic of his country, and thereby cultivated what he called “articulate citizens”--those who would go on to lead the nation in bringing its practice more in line with its principles.

But Ellison’s fame drew the ire of black nationalists during the 1960s. As a black writer, he was expected to “fight the power,” not preach the glories of the Declaration of Independence. Ellison’s devotion to the Constitution as “the still-vital covenant by which Americans of diverse backgrounds, religions, races and interests are bound” was too much for those seeking to profit by the confusion of the post-civil rights era.

No one was more mindful than Ellison that diversity, in and of itself, does not automatically produce unity. According to the invisible man, “It’s ‘winner take nothing’ that is the great truth of our country or of any country.”

As a minority of one, “Invisible Man’s” narrator offers an ode to the national motto, E pluribus unum: “America is woven of many strands; I would recognize them and let it so remain.”

He touts the diversity of each individual and not the mayhem of multiculturalism that has balkanized college campuses and entrenched a system of color-coded benefits and burdens. “Let man keep his many parts,” the invisible man suggests, “and you’ll have no tyrant states.”

Although Ellison only published one novel during his life, the lesson taught by his invisible man is as valid today--that the government of all must be partial to none. Even more important, as Ellison put it, “the obligation of making oneself seen and heard [is] an imperative of American democratic individualism.”

*

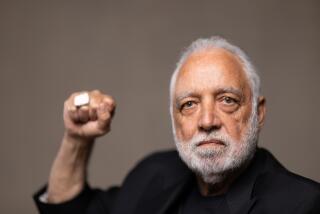

Lucas Morel is assistant professor of politics at Washington and Lee University and editor of the forthcoming “Raft of Hope: Ralph Ellison’s ‘Invisible Man’ and the Politics of the American Novel.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.