Use of Eye Cells in Treating Parkinson’s Shows Promise

- Share via

A new type of cell transplant to treat Parkinson’s disease appears to significantly improve patients’ movements while avoiding the ethical quandaries linked to fetal and stem cell use.

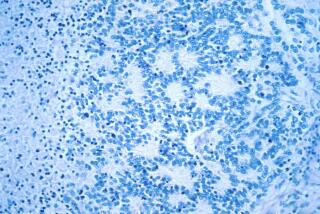

The technique, which so far has been tested only in six patients, uses eye cells obtained from a cadaver donor. These retinal pigment epithelial cells, isolated from the retina, produce dopamine--a neurotransmitter that is present in abnormally low quantities in the brains of Parkinson’s victims--although researchers do not yet know why the cells do so.

But what makes the cell treatment particularly attractive is that these cells can easily be grown in the laboratory. A small number of cells from a single eye can be cultured to produce hundreds of millions of cells, enough to treat thousands of patients, said Dr. Louis R. Bucalo, president of Titan Pharmaceuticals Inc. of South San Francisco, which makes the transplant material.

Titan attaches the cells to microscopic gelatin beads, which help them grow. The company calls the finished product Spheramine.

Dr. Ray Watts of the Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta and his colleagues implanted Spheramine cells in six patients with a moderate form of Parkinson’s. They drilled five holes through each patient’s skull on one side of the head, then used a long, thin needle to inject a total of 325,000 cells into each patient’s striatum, the area of the brain that controls movement.

Watts reported last week at a Denver meeting of the American Academy of Neurology that, one year after the implants, the patients averaged a 50% improvement in motor function on a Parkinson’s assessment scale. One patient has now had the implant for two years with no loss of benefit.

“This is as good as, or better than, any other current therapy,” Watts said.

Parkinson’s, which strikes as many as 100,000 Americans each year, is characterized by severe tremors and rigidity in the limbs and loss of muscle control. Although its primary cause is unknown, the disorder results from the death of brain cells that produce dopamine, which plays a key role in transmitting commands from the brain’s muscle-control centers.

The first line of treatment is the use of drugs, such as l-dopa, that stimulate production of dopamine, but such drugs lose their effect over time as the number of dopamine-producing cells continues to decline.

Surgeons have tried implanting a variety of dopamine-producing cells into the brain with mixed results. The first attempts were with cells from the patient’s own adrenal glands, which produced initial improvements in motion. “But adult cells do not survive very long in the brain,” Bucalo said.

The greatest amount of work has been done with fetal brain cells, which survive much longer than adult cells. At the Denver meeting, Dr. Curt Freed of the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center updated his studies on 32 patients who received fetal cell grafts for advanced Parkinson’s. He said the procedure works best in patients who are younger than 60 and who respond well to drug therapy.

But he also noted that 15% of the patients exhibited uncontrolled jerking movements and other side effects resulting from too much production of dopamine by the implanted cells. In these cases, the team had to administer drugs to reduce dopamine production or use a type of brain pacemaker to reduce the unwanted movements.

The biggest problem with fetal cell transplants is that it is difficult to obtain human fetal cells because of religious and ethical objections to their use in experiments, as well as federal restrictions on funding such research. The Titan approach, Bucalo said, eliminates this problem.

Titan hopes to begin a larger clinical trial later this year in which Watts and other neurosurgeons will enroll as many as 80 patients. Those patients will receive injections of the cells on both sides of their brains, which Watts hopes will increase the efficacy of the implants. Half of the patients will receive the implants and half will undergo a sham operation.

Even if the larger study replicates the findings, it would still be several years before the technique could be in widespread use.

“We have to take [the current results] with a grain of salt because we can not rule out some placebo effect,” Watts said. “We must move to a controlled study to prove that it works beyond a shadow of a doubt.”