Lott’s Fall Is Signaling a Shift From Old South to New Breed

- Share via

ATLANTA -- Strom Thurmond and Jesse Helms won’t be back. Trent Lott will, but not as Republican leader in the U.S. Senate.

Lott’s decision to relinquish the post marks another shift in the look of GOP politics in the South, where an old guard of former segregationists is giving way to a new breed of leaders, political experts say. Lott, who was elected to Congress in 1972, the same year as Helms, was among a group of former Democrats who cut their teeth in the segregationist South and switched parties as the Republican Party gained sway in the region.

“You’ve got Thurmond and Helms leaving and Lott left neutered.... It’s kind of a generational replacement of leadership,” said Merle Black, an expert on Southern politics at Emory University in Atlanta.

The Republicans have converted the South into a reliable base since the 1960s, when the party capitalized on the resentment among conservative rural whites, many of them raised as Democrats, toward new federal civil rights measures. The so-called Southern strategy, personified by politicians such as Lott, who began in politics as a congressional aide to a segregationist Democrat, became a linchpin of GOP campaigning nationwide.

The new flock of Southern Republicans tends to be more moderate and more likely to be concerned with the anxieties of the region’s swelling ranks of moderate suburbanites, who hold the critical swing votes in modern campaigns in the South. While the votes of rural white residents are still crucial to the GOP, there is also now reason to appeal to the increasing rolls of voters who’ve moved from other regions of the country and to a growing share of Latino and Asian American voters.

“The South has changed and a lot of people haven’t been noticing -- until you get to a defining moment like this and see a passing of the torch,” said Ralph Reed, chairman of the Republican Party in Georgia. He said the GOP in the South has grown more inclusive.

Lott’s expected replacement as majority leader, Sen. Bill Frist of Tennessee, reflects a shift in background. Though generally conservative and a Southerner, Frist was schooled in the Ivy League and entered politics in the 1990s, at age 42, after a successful career as a surgeon. Unlike Lott, he has little connection to the politics of the South’s racially divided past, analysts said.

“His background is medicine and business. It is not old-time, segregationist politics,” said Hastings Wyman, who publishes the Southern Political Report, a biweekly newsletter.

Observers said Frist embodies the “compassionate conservatism” espoused by President Bush -- a philosophy favoring low taxes and less government but more accommodating on social matters. “Frist is a very different generation of politician,” Black said. “Frist could go anywhere in the country and be perceived as reasonable.”

Moderate Republicans did well in the South this year. Thurmond and Helms will be replaced by successors viewed as less conservative. Rep. Lindsey O. Graham takes the South Carolina seat that Thurmond held since 1954. Elizabeth Hanford Dole, a former Cabinet member, succeeds Helms in North Carolina. GOP moderates edged out conservative primary opponents in gubernatorial contests in Alabama and South Carolina, in a Senate race in Louisiana and two congressional campaigns in Georgia.

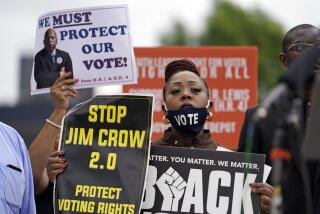

Many are waiting to see whether the racial sensitivities raised during the Lott episode will affect political contests in the South, where Democrats have long accused the GOP of subtly using racial antagonisms to garner white votes. Overt racial rhetoric disappeared from Southern campaigns years ago, but emotions remain strong in debates over racially tinged symbols, such as the Confederate battle flag.

Some experts said the widespread condemnation across racial lines of Lott’s apparent endorsement of the segregationist policies of Thurmond’s 1948 presidential campaign illustrated the possible pitfalls of racial insensitivity. The controversy may have dealt a severe blow to the efforts of Confederate flag supporters to restore the emblem to its former prominent size on the Georgia state flag.

The Lott case presents Southern Republicans with “a moment of examination of conscience,” said Ferrel Guillory, director of the Program in Southern Politics, Media and Public Life at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “Having built this party and having succeeded, to what extent do they want to continue to be defined by themes like states’ rights, opposition to affirmative action? Or do they generate a new agenda, even at the risk of alienating some supporters?”

He added: “The Republicans remain a strong political force in the South. This is not Watergate. But it may influence the tone and texture of political dialogue.”

One Democratic consultant remained skeptical. “Republicans, as part of the Southern strategy, have danced with the devil,” said Tim Phillips, who managed the campaign of Georgia Gov. Roy Barnes, a Democrat defeated in November. “This doesn’t set new rules. It just reminds us what the rules are.”

*

Echoes of the Dixiecrat era

Objecting to their party’s civil rights program, a group of Southern Democrats broke away to form the States’ Rights Democrats in 1948. The right-wing splinter organization, labeled the “Dixiecrats” by Bill Weisner of the Charlotte News, nominated South Carolina Gov. Strom Thurmond for president and Mississippi Gov. Fielding Wright as his running mate. The ticket carried South Carolina, Mississippi, Louisiana and Alabama, receiving 39 electoral votes and more than 1 million popular votes. These quotes are from and about that era:

“We stand for the segregation of the races and the racial integrity of each race. ... We oppose and condemn the action of the Democratic convention in sponsoring a civil rights program calling for the elimination of segregation. ... We affirm that effective enforcement of such a program would be utterly destructive of the social, economic and political life of the Southern people.”

--Official platform of 1948, States’ Rights Democrats.

“I want to tell you that there’s not enough troops in the Army to force the Southern people to break down segregation and admit the Negro race into our theaters, into our swimming pools, into our homes and into our churches.”

--Thurmond, accepting the States’ Rights party nomination for president in 1948.

“If the South should vote for Truman this year, we might just as well petition the government to give us colonial status.”

--Thurmond, in his 1948 acceptance speech, commenting on the decreasing power of Southerners within the Democratic Party.

“Every American has lost part of his fundamental rights.”

--Thurmond, after the Supreme Court in 1948 threw out South Carolina’s white primary, decreeing that the party could not bar blacks from voting.

“One of the most astounding theories ever advanced is that the federal government by passing a law can force the white people of the South to accept into their businesses, their schools, their places of amusement, and in other public places, those they do not want to accept.”

--Thurmond, 1948.

“You know, if we had elected this man 30 years ago, we wouldn’t be in the mess we are today.”

--Then-Rep. Trent Lott (R-Miss.) in 1980.

“I probably made some statements I do not agree with now.”

--Thurmond, in 1998.

“I want to say this about my state: When Strom Thurmond ran for president, we voted for him. We’re proud of it. And if the rest of the country had followed our lead, we wouldn’t have had all these problems over all these years, either.”

--Sen. Lott, Dec. 5, at Thurmond’s 100th birthday party.

Sources:

“National Party Platforms, Vol. 1, 1840-1956;” “Strom Thurmond and the Politics of Southern Change,” by Nadine Cohodas, 1993; “Facts on File, 1948-49;” “National Party Conventions, 1831-1996,” by Congressional Quarterly; Washington Post; Post and Courier, Charleston, S.C.; Clarion-Ledger, Jackson, Miss.

Researched by John Tyrrell, Times librarian.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.