Practicing what he teaches

- Share via

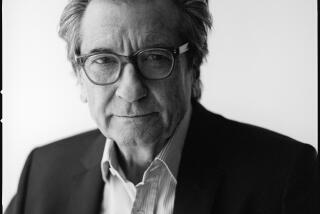

When Frederic Tuten talks, the literati listen. Better still, they do what he asks.

When the novelist and longtime creative writing professor asked Susan Sontag, Edna O’Brien and Donald Barthelme to teach fiction-writing courses at his distinctly non-Ivy League school, City College of New York, they did. More recently, when the personable Tuten asked his friend Steve Martin to call an interviewer regarding his latest novel, “The Green Hour,” the phone rang minutes later.

Diane Keaton puts him up when he’s in L.A., one of the perks of Tuten’s gift for friendship. And when he directed City’s graduate program in literature and creative writing (he retired in 1995 but hasn’t cut the cord), he helped nurture a new generation of bestselling writers, among them novelists Oscar Hijuelos and Walter Mosley. But Hijuelos says emotional intelligence only begins to explain Tuten’s magnetism.

“Frederic has always had a romantic vision of literature that’s quite infectious,” says Hijuelos, who also picked up the phone at Tuten’s request. “I see all these young writing students who are getting conned by writing teachers who are hucksters, and Frederic isn’t.”

Sales of Tuten’s five novels may not have reached the rarefied heights of some of those he mentored (although he did join Hijuelos and Mosley on The Times’ 100 Best Books of 2002 list). But in literary circles, he is a celebrity of sorts. His “The Green Hour” (W.W. Norton & Co.) scored a three-page review in the New Yorker by the godfather of postwar fiction, John Updike. And he was among a small circle of people whom Martin asked for comment on the manuscript for his upcoming novel, “The Pleasure of My Company,” which will be published by Hyperion next fall.

“He’s the smartest guy I know,” Martin says. “I really, really like his work. I like that it’s readable and erudite. It’s what you go to a book for or a play for. You go to a movie to be entertained. You go to a play to be entertained and informed.”

Yet mainstream readers aren’t going to Tuten’s books, judging by his relentless exclusion from the roster of household names in culture and his abiding status as a writer’s writer.

West Coast infatuation

Tuten is blissful. He’s savoring a lunch of red meat at the airy Maple Drive restaurant and recounting his rainy arrival in Los Angeles a few days earlier. A tall man with close-cropped gray hair and SoHo-friendly black glasses, he describes the city in nearly mystical terms that doubtless failed to occur to that day’s beleaguered commuters.

“It was very beautiful and haunting to see these buildings wrapped in fog,” he says. “They were lyrical. They were magical. And I’d never seen Los Angeles that way. Ever. I thought, now I recognize it as something that’s familiar to my life.”

Of course, familiarity has a nasty habit of breeding contempt, and Tuten is happier to be basking in the city’s born-again sunshine, which is elbowing its way into the restaurant. At 66, the lifelong New Yorker is discovering that living at the center of the literary universe isn’t sufficient compensation to keep him there, and he’s contemplating an extended stay in L.A. Indeed, Tuten’s new infatuation with the West Coast is a departure after a lifetime of looking toward Europe for his cultural cues.

Not surprisingly, the heroine of “The Green Hour,” a stunning redhead named Dominique, shares his Eurocentrism as well as his passion for art. Some of Tuten’s best friends are artists of the boldfaced-name variety. New York magazine, which puts a lot of stock in such things, admiringly noted that he’s a regular in the Hamptons enclave that includes such ‘80s superstars as David Salle and Eric Fischl. (For his part, Tuten grumbles that he’s sick of the Hamptons and its monotonous population of rich people.)

Tuten’s best friend was Roy Lichtenstein, whom he still mourns five years after the artist’s death at 73. “We knew each other for 35 years,” Tuten says. “We saw each other three times a week, if not more. We were really deep friends, and he was the older friend and, in a way, deeply wiser friend. You don’t replace wisdom with youth. I miss him immensely. And there are other friends over the years, one by one going.”

Tuten grapples with the themes of art and death in the story of Dominique, a brilliant art historian who pursues both scholarly research and futile passion in Paris.

She is helplessly bound to a revolutionary drifter and fellow fiery redhead who loves her and leaves her and loves her again, cruelly repeating the cycle over and over. (Dominique’s flawed lover, Rex, shares the name of Tuten’s feckless father, who disappeared when Tuten was 10.)

Dominique fends off another suitor, the handsome, rich Eric, until doing so strikes even her as pointless, and eventually finds salvation in her love for a child -- Rex’s love child with another woman.

Although death claims none of the characters prematurely, it is nonetheless a constant presence. Dominique, a cancer survivor, returns repeatedly to the disturbing inscription on one of her favorite paintings by Poussin, “The Arcadian Shepherds,” in which Death says “et in Arcadia ego” (even in Arcadia, I am).

“The Green Hour” refers to the slice of early evening when “everyone in Paris went to the cafes to drown themselves in milky green absinthe,” Dominique says.

Reactions to the book are mixed, ranging from glowing praise for Tuten’s artistry -- The Times’ reviewer called him “an exceptional writer [who] is frequently elegant and always intelligent in his spiritual accounting” -- to disdain for Dominique.

Novelist Carolyn See wrote in the Washington Post that she found it “just hard to believe that again and again Dominique would choose a Marxist blowhard over a handsome, wealthy, powerful, kind, absolutely devoted man who wants to marry her and give her everything in the world,” and Updike chastised Dominique for her “vacillating, unconsciously arrogant infatuation.”

Tuten defends his book like a father hen. “I think many critics extrapolated their feelings about what they themselves would like people to do in life. If you’re with someone who isn’t kind to you, you should walk out. If someone betrays you, turn around. But that’s life. If you had said the drama fails, then I understand. But you’re really saying, ‘Why would anyone in a sane mind want to reject a wonderfully handsome attractive man who’s in love with you who also happens to be a trillionaire for someone who’s not those things?’

“But this is the point of the book. That’s what passion is about. That’s what the unreason of life is about and that’s what makes us all interesting. We don’t always make choices that are the best for us, and that’s what gives us our complexity and our tragedy.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.