Vaccine for AIDS Shows Promise

- Share via

SEATTLE — The first human studies of a highly anticipated proposed AIDS vaccine indicate that it produces a response in the immune system that may help keep HIV infections in check, researchers said Tuesday.

If the vaccine ultimately is proved to work--something that won’t be known for several years--it would be given to people after they are infected. The aim would be to limit the ability of the virus to replicate itself, keeping it at a manageable level and slowing--perhaps blocking--the onset of AIDS.

Last month, Merck, which is developing the vaccine, announced the results of studies showing that the vaccine can sharply reduce HIV replication in monkeys.

Those results seemed so promising that Dr. Emilio A. Emini of Merck Research Laboratories was asked to report on human studies at the Ninth Annual Retrovirus Conference taking place here--even though the studies are still at a very early stage.

The first trials in a relatively small number of people have shown that the proposed vaccine is apparently safe. The vaccine also has the same type of impact on the immune system in humans as previously seen in monkeys, Emini said, although the trials were in people who are not infected with HIV.

“We are encouraged,” Emini told conference attendees, but he cautioned that it will be at least a year before the company finishes the current safety trials of the vaccine. If those prove successful, further testing could require an additional four years at least, he said.

Dr. David Gold, vice president of the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative, called the results “significant findings,” although he too cautioned that “there are still a lot of details that need to be fleshed out.”

“Developing a vaccine is a lot more complicated than developing a drug,” he said.

“We’re still a long way from having a vaccine that would protect people,” said Lee Klosinski of AIDS Project L.A. But Merck’s willingness to invest so much money on the early trials “shows they have tremendous confidence they are on to something,” he added.

Researchers were highly optimistic about the development of an HIV vaccine when the AIDS epidemic was first noted 20 years ago, but that optimism soon gave way to growing pessimism.

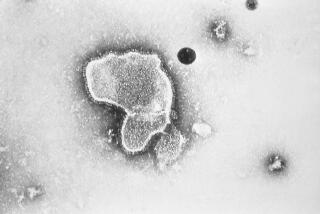

Unlike other deadly viruses that have yielded to the efforts of vaccine researchers, the AIDS virus has the ability to rapidly change its surface coat. The changes allow the virus to elude antibodies the immune system might direct against an infection.

Because of that trait, many vaccine researchers have abandoned--or at least postponed--hopes of a vaccine that would block an infection altogether. Instead, the emphasis of Emini and other researchers has been on finding a vaccine that would control viral replication after an infection has already occurred.

The body controls such infections using specialized white blood cells called CD4 and CD8 cells. These immune cells attack and destroy HIV-infected cells, thereby limiting spread of the virus to other cells. This process is called cell-mediated immunity.

The Merck team has concentrated on the DNA that serves as the blueprint for a protein called gag. The protein itself is harmless but is part of the HIV virus.

In one project, the researchers have incorporated the gene that tells the body how to produce gag into a circle of DNA that can be injected directly into muscle. Once in the body, the gene stimulates production of the gag protein. That, in turn, triggers an immune response--boosting production of CD4 and CD8 cells that then attack cells infected by HIV. Researchers call this approach naked DNA.

In a second project, they incorporated the gag gene into a type of virus called an adenovirus. Normally the adenovirus causes colds, but the ones used in the research have been modified so that they do not produce disease. Again, the gag gene stimulates production of gag protein. Typically, genes incorporated into a delivery mechanism such as a virus stimulate a stronger immune response than naked DNA.

The team reported last month that they could prime monkeys’ immune systems with the naked DNA, then boost the immune response with the adenovirus vector. Monkeys given this prime-boost regimen had significantly lower levels of a monkey AIDS virus in their blood than did unvaccinated monkeys.

The benefits were attributed to increased levels of CD4 and CD8 cells stimulated by the vaccine.

In the human experiments on which Emini reported Tuesday, naked DNA and the adenovirus vector were each administered alone.

With the naked DNA, Emini found that 16 of 38 volunteers showed increased levels of CD4 and CD8 cells after 30 weeks. “That shows that the immune system is ‘seeing’ the DNA,” he said.

With the adenovirus vector, he said, about two-thirds of the recipients showed increased levels of the immune cells.

The team has begun giving the prime-boost regimen to some uninfected volunteers, but does not yet have any results, he added. They will also soon begin giving the vaccine to HIV-positive volunteers. The initial safety trials will include at least 600 people.

One potential impediment to the vaccine’s success is that many potential recipients already have some immunity to the adenovirus that is used as a vector. Presumably, at some time in the past they have had a cold caused by that particular adenovirus. But Emini said he is hopeful they can overcome that immunity by using higher doses of the vaccine.

The Merck team hopes that their approach will prove more effective than the other potential vaccines that are now in or nearing clinical trials. One of them, the AIDSVax vaccine, is a more traditional vaccine that is designed to produce antibodies to the viral coat. It has been tested in nearly 8,000 volunteers, and results of those trials are expected later this year.