Offices of lasting influence

- Share via

Washington — The West Wing -- the building, not the TV show -- has just turned 100, and no one would be more surprised at its place in the popular imagination than its original congressional critics, who despaired that the addition cheapened the White House.

Compared with the over-the-top wedding-cake architecture of the early 1900s, its design seemed so spartan that many in Congress agreed with Sen. Jacob Gallinger (R-N.H.) that it looked like “the offices of second-class lawyers and third-rate doctors.”

Aesthetics aside, many had difficulty understanding why a president needed separate offices for carrying out the country’s business. Gentlemen of the time received business visitors in their home offices, historian William Seale said, and “in Congress, the idea of the president not working in the historic White House residence was vociferously opposed.” He adds that “the new wing was so controversial, it was called the temporary executive office building.”

But the $65,000 renovation project, inspired by Teddy Roosevelt, who first worked in the new presidential offices on Nov. 5, 1902, brought enduring change to both the mansion and the president’s work habits. The addition of the West Wing -- meant to replace the warren of desks crammed into the second floor of the residence -- in some sense “institutionalized the presidency,” said Seale, author of a two-volume history of the White House, “The President’s House.”

At the very least, it professionalized the staff, helping the White House evolve from a place where a president’s nephews or sons took down his correspondence to a center of high-wire political power where generations of Sam Seaborn/George Stephanopoulos types would gild their resumes.

Stripped of its ornate Victorian decor, with its quaint 19th century ways replaced by a quieter classiness, the business side of the White House became a muscular bully pulpit for presidents and a symbolic locus of power for the nation, later for the world.

It may seem odd to celebrate the 100th anniversary of a remodeling project, even such a famous one. But in this case, Seale said, “what we celebrate without saying so is the 20th century.”

Modern sensibility

It wasn’t a given that the power of the presidency would reside at 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. over the long term. One plan, considered by Ulysses S. Grant, was to move the residence to Rock Creek Park, where proponents envisioned a huge presidential mansion with voluminous grounds, much like those of the great European capitals.

But, Seale said, Abraham Lincoln had “sanctified the White House” with his handling of the Civil War. When two aides, John Hay and George Nicolay, published a book of his speeches after his 1865 assassination, they were astonished by the outpouring of affection for Lincoln’s words. The public clearly believed that he had been a great man serving a valiant cause.

That perception helped cement presidential power in Lincoln’s final home, but it did not prevent repeated efforts to turn the White House into a grand palace. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had elaborate ideas of erecting an enormous building with courtyards and a huge wing to the west of the residence. William McKinley approved the plans, but in 1901, before work could begin, he was assassinated, and Vice President Roosevelt assumed office.

The White House had never seen anything quite like the new first family. With six children, assorted cats, dogs, snakes, raccoons, a macaw and one pony -- it spurred the need for a $500,000 renovation of the residence. But first lady Edith Roosevelt, influenced perhaps by a cousin, author Edith Wharton, rejected the Beaux Arts design left on McKinley’s desk. Seale believes she knew her husband was a larger-than-life character who needed a less fussy backdrop.

“This was a switch to a modern sensibility,” agreed William Bushong, historian and Web master of the White House Historical Assn. site, whha.org. “This was the progressive era, with the city beautiful movement, rise of the professions, interest in experts.”

Architect Charles McKim, a partner of Stanford White and William Rutherford Mead, peeled off florid decorations, doubled the size of the family quarters and, to the west, dismantled the greenhouses and laundry rooms that rested against the house.

In their place, he built the wing of offices that would eventually house the main levers of American power. Seven years later, in 1909, builders added the West Wing’s Oval Office, although it did not acquire that nickname, according to former Time magazine correspondent Hugh Sidey, chairman of the association, “until television put the presidency and the White House on a world-encompassing electronic stage.”

The West Wing quickly became part of the lore of American leadership. The image of a president sitting at his desk, alone with power, has been burned into the American psyche.

But even as late as the 1940s, it was not unthinkable to propose moving the president’s home to a new locale. Harry Truman, his White House a crumbling mess of ancient plumbing, creaky walls and shaky foundations, asked Congress for money to remodel. In response, House Appropriations Committee Chairman Clarence Cannon (D-Mo.), went one step further, suggesting that the house be torn down and rebuilt.

Truman, however, like Grant before him, understood that history -- and especially Lincoln’s legacy -- resonated from the White House walls. The public, and presidential authority, required its restoration. “As you know,” Truman wrote Cannon in response to his offer of demolition, “the room where the Emancipation Proclamation was signed has a plaque on the mantle.”

Anniversary symposium

A half century later, the White House is safe from the wrecking ball. And at 100, the West Wing is synonymous with power and the decisions that transform politicians into presidents.

To mark the West Wing centennial, the White House Historical Assn. is holding a symposium in Washington on Tuesday and Wednesday called Workshop of Democracy. Along with lectures about the West Wing during crises, panel discussions about the role of the press and an exhibition of photographs, the symposium will include the world premiere of “None But Honest and Wise Men,” a documentary by L.A. filmmaker Chuck Workman.

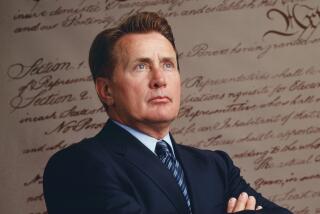

“The idea was to profile a dozen presidents in a particular crisis,” said Workman, who specialized in documentaries about the art world and often produces the film montages for the Oscar show. “We chose to do it in different styles that reflected on each president.” So Truman appears in newsreels and John F. Kennedy’s segment has the look of a documentary portrait. For Teddy Roosevelt, the filmmakers found silent movies, and for Lincoln they shot in an African American church in Los Angeles, interspersing comments about Lincoln’s import with photographs of him at work. There are split screens for Lyndon Johnson, interviews with the living presidents, and clips from movies featuring every president from Michael Douglas to Harrison Ford.

And recurring in the background are the offices of the West Wing, the set of rooms that gave form to function and helped shape the American presidency.