Updike the artist draws a woman as real as Rabbit

- Share via

Amaster craftsman of language, John Updike also studied as a young man to become a painter. His writing has always reflected his keen eye for the visible world but now, in his 20th novel, his sense of the visual achieves its apotheosis.

“Seek My Face” is the story of a female painter whose life -- artistic and personal -- has made her a key figure in the history of American postwar art. A respected artist in her own right, Hope Chafetz is equally famous as the wife of art legend Zack McCoy, the hard-drinking, dazzlingly original Abstract Expressionist whose fiery life was extinguished in a car crash. Hope later married the central figure of Pop Art, Guy Holloway, before finding a more conventional kind of marital bliss with businessman and art collector Jerry Chafetz, now deceased.

The story unfolds within the confines of a single chilly April day. Hope is being interviewed by an artsy young woman from New York who has driven up to her rustic home in Vermont. “Interviews and critics,” Hope feels, “are the enemies of mystery, the indeterminacy that gives art life.”

Yet, here she is, at 79, somewhat to her own surprise, telling the interviewer more about her private life than the interviewer has asked to know. The young woman’s pointed questions spur Hope into hitting back with even more provocative answers. Yet she does not tell all, not only because of a certain residual reticence but also because the interviewer does not seem to need quite as much material as Hope has to offer.

Consumed, as an artist and a woman, by the desire to give of herself, Hope “has never learned how little the world needs us to give....” We as readers, however, are privy to all that Hope leaves unspoken.

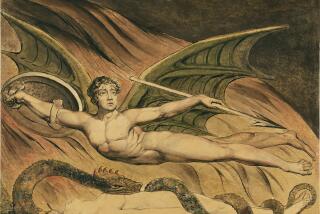

Although it is impossible not to see “Zack McCoy” as Jackson Pollock (almost every detail about Zack’s life and work comes from Pollock’s), it is not especially rewarding to read this novel as a roman a clef. The parallels are suggestive but do not match. Pop icon Guy Holloway may have a place in the city like Andy Warhol’s “Factory,” where he films the sexual antics of drugged-out youth (Holloway’s is amusingly called the “Hospice”), but he also has attributes of other Pop artists, like Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns.

And Hope, like Pollock’s wife Lee Krasner, plays a vital role in supporting her husband’s work and is herself a noted artist, but the resemblance ends there. Krasner, the daughter of a Russian Jewish immigrant family in New York, did not remarry, and she seems to have been a less tentative personality than Hope, the child of Pennsylvania Quakers. Indeed, apart from her gender, the real-life person whom Hope most resembles is her creator, Updike.

Hope’s reflections on the course of American art in the latter half of the 20th century express her sympathetic understanding of the passions and ideals that motivated these artists and movements, but they also reveal the degree of her estrangement from them.

“There are times,” she tells her interviewer, “when this whole art business, which has been my life of course, seems terribly transitory and disposable. I go to museums now and look at the oversize, boastful canvases by Zack and Phil and Jarl and it all seems so tired....” Unlike the Old Masters, or even Picasso, their colors have shifted, dulled or faded: “Zack and the others got away from permanence, they didn’t grind their own pigments or have apprentices do it for them, they took what materials were for sale around them.”

As for the playful Pop Art that came tripping lightly in the wake of the Abstract Expressionist Sturm und Drang, Hope appreciates its nimble wit and genuine craftsmanship, but she can scarcely revere it. In Pop icon Holloway, a detached and disciplined man with a keen sense of the ever-changing art market, Updike has created a character who embodies the creeping sense of cynicism that dogs the contemporary art scene.

Hope’s own artistic vision is different from Zack’s or Guy’s. It involves a spiritual dimension, a sense of how precious -- perhaps even sacred -- a gift is consciousness itself: “[H]ow marvelous ... the incredible biological machinery that gives us consciousness, and how we mostly just throw it away, even if we don’t commit suicide, we presume to find life dull and be bored most of the time, and discontented, and just waste it.” Art, for Hope, is the quest to lend permanence to the transitory radiance of life.

Hope’s paintings are her attempts to embody this radiance. Updike’s deeply felt portrait of Hope’s consciousness is his. For perhaps the first time in his long career as a novelist, Updike has created a female character as complex and fully credible as his Rabbit Angstrom.

Whether as a little girl encountering her first pictures or as an elderly woman looking at the afternoon landscape, Hope has a poignancy and luminosity that will linger in the readers’ consciousness long after they have finished the book.

*

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

Seek My Face

A Novel

John Updike

Alfred A. Knopf: 288 pages, $23

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.