Richard Holmes, 73; Fought for ‘Death With Dignity’ Law

- Share via

Richard L. Holmes, who became a central figure in thwarting a federal challenge to Oregon’s Death With Dignity Act, has died of colon and liver cancer. He was 73.

Holmes died Monday in his Portland home, surrounded by his family.

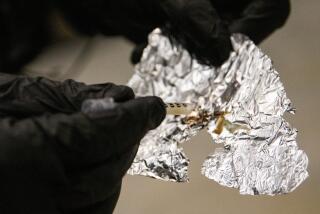

He never took the fatal dose of Nembutal he had fought so hard to obtain.

Holmes had always said he might never drink the deadly cocktail, but he felt better knowing the $117 prescription was stored in his cool basement.

“I want the option. I want a choice,” he told The Times on Nov. 7 last year. “That’s all I want.”

A couple of weeks before that, two doctors had confirmed that Holmes had less than six months to live, and that he was mentally competent to decide when and if he wished to take his own life.

Their decision, after a 15-day waiting period, would qualify him for a lethal prescription of barbiturates under the Death With Dignity Act, passed by state voters in 1994 and again in 1997.

Oregon officials say that 91 people, most suffering from cancer, have used the law to speed their deaths, and that at least 10 times that number, like Holmes, have obtained the lethal medication but never used it.

Holmes’ prescription was to be filled, after the 15-day waiting period, on Nov. 9, 2001.

But on Nov. 6, U.S. Atty. Gen. John Ashcroft attacked the state law by ordering federal drug agents to revoke the licenses of any doctors prescribing the fatal dosages.

Before Ashcroft launched the administrative assault, the Oregon law--the only one of its kind in the country--had survived a federal court challenge, a repeal attempt and two congressional override efforts.

Prevented from obtaining his own fatal prescription, Holmes joined Oregon officials, a handful of other terminally ill patients and the Compassion in Dying Federation of Oregon to challenge the Ashcroft directive in court.

A federal judge in Portland temporarily blocked the attorney general’s order, and in late November, Holmes did have his comforting medicine of choice in his hand.

On April 17, the federal court ruled that Ashcroft and the U.S. Department of Justice could not interfere with the state’s law, after Oregon Atty. Gen. Hardy Myers successfully argued that regulating doctors is the sole responsibility of states rather than the federal government.

The case is now on appeal.

“When the quality of my life is not worth living, then I want to stop living,” Holmes said when the court case was heard last spring. “It should be my decision.”

Born in Portland, Holmes attended the University of Portland, then sold swimming pools in the San Fernando Valley for many years.

After returning to his hometown, he sold burglar alarm parts until his retirement.

He spent the last eight years in and out of hospitals, beginning with double heart bypass surgery in 1994. A year later, he had a liver transplant.

In 2000, Holmes was diagnosed with colon cancer, and underwent surgery and a lengthy course of chemotherapy. Then the cancer spread to his liver, where it was diagnosed as inoperable.

Early last November, Holmes told The Times he expected to live no more than four to six months, even if he never obtained the prescription to hasten his demise.

He lived nine months.

Holmes is survived by his son, Richard L. Holmes; his daughter, Cindy M. Taylor; his brother, Dr. David M. Holmes; and four grandchildren.

A memorial service is planned for Monday at O’Connors Restaurant in Portland.

Memorial donations may be sent to the Compassion in Dying Federation of Oregon.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.