‘Person of Interest’ in Anthrax Investigation Seeks Damages

- Share via

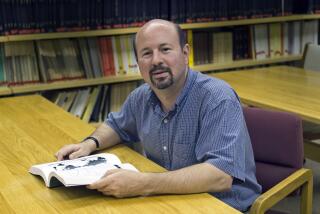

WASHINGTON — Steven J. Hatfill, the former Army biomedical researcher deemed a “person of interest” in the October 2001 anthrax attacks, struck back at the government Tuesday, filing a lawsuit in federal court alleging a yearlong campaign of harassment and illegal conduct against him led by Atty. Gen. John Ashcroft.

In a 40-page complaint filed in U.S. District Court, Hatfill accused the Justice Department and the FBI of orchestrating a series of leaks that violated federal privacy laws and other federal guidelines designed to protect innocent citizens. He seeks an injunction to curb the investigation of him, and unspecified monetary damages.

“For more than a year now, Dr. Hatfill has been questioned, searched, bugged and tailed by the FBI. Dr. Hatfill had nothing to do with the horrific anthrax attacks,” his attorney, Thomas Connolly, a former federal prosecutor, said on the steps of the federal courthouse after filing the suit.

“No evidence links Dr. Hatfill to the crime, yet the attorney general and a number of his subordinates have attempted to make him the scapegoat,” Connolly added. “In the process, they have trampled Dr. Hatfill’s constitutional rights and destroyed his life.”

A Justice Department spokesman declined comment on the suit. Earlier this year, the department’s Office of Professional Responsibility, which investigates cases of alleged misconduct by employees, concluded that Ashcroft had not engaged in any professional misconduct or violated any law in connection with the anthrax investigation.

In his suit, Hatfill labeled efforts by the office to investigate the department’s treatment of him as “halfhearted.”

The complaint paints the picture of a government under intense pressure to solve the anthrax attacks, which killed five people and paralyzed a region already traumatized after Sept. 11. The FBI, the suit contends, was also stressed because some members of Congress were weighing stripping the bureau of its domestic intelligence-gathering role because of intelligence failures leading up to the terrorist attacks. A driving force in the investigation, the suit contends, was Barbara Hatch Rosenberg, a bioweapons expert at the State University of New York at Purchase, who in the early months of 2002 embarked on a campaign to convince investigators that Hatfill should be their prime suspect, according to the suit.

Rosenberg, who was not named as a defendant in the suit, could not be reached for comment.

The suit describes a meeting in June 2002 that Rosenberg had with the staffs of Patrick J. Leahy (D-Vt.) and Tom Daschle (D-S.D.), the two senators to whom anthrax-laden letters were addressed, that was also attended by Van Harp, the FBI’s top supervisory agent on the anthrax investigation. After the meeting, according to the suit, Harp “directed the full attention in the direction of Dr. Hatfill.”

According to Connolly, the resulting investigation has been “Kafkaesque” and illegal.

A week after the meeting, the suit alleges, the FBI, in the first of scores of leaks, tipped off reporters that Hatfill had consented to a search of his Frederick, Md., apartment. The search was broadcast on national television and the media began scrutinizing details of his life.

Other alleged leaks cited in the suit were on topics ranging from Hatfill’s performance on polygraph examinations to the reaction of FBI bloodhounds in his presence.

The suit alleges that the Justice Department cost him a $150,000-a-year biomedical research position that he landed in May 2002 at Louisiana State University.

It cites an e-mail from a Justice official ordering the university to “cease and desist” from using Hatfill on Justice Department-funded projects.

“As Dr. Hatfill had been hired specifically for these duties, Mr. Ashcroft’s Department of Justice effectively ordered the employer of a presumptively innocent Dr. Hatfill to terminate him from his employment,” the suit contends.

The suit also takes Ashcroft to task for giving interviews and making statements labeling Hatfill a “person of interest” to investigators in the case.

While law enforcement officials often label people suspects in cases, the suit says the “person of interest” designation has never been used by a sitting attorney general, and has no legal significance. But it exposed Hatfill to further ridicule and denied him the presumption of innocence guaranteed under the Constitution, the suit contends.

The suit alleges that the government’s course of conduct has violated the federal Privacy Act as well as Justice Department regulations and guidelines covering when law enforcement officials may publicly disclose aspects of an ongoing investigation.

Since a 1971 U.S. Supreme Court case, individual citizens have been able to seek monetary damages from federal employees acting “under color of legal authority” for violating their rights.

But those cases have been exceedingly hard to win. Often, officials are able to argue that leaks of damaging evidence were unauthorized, for instance.

“The law gives members of the federal government, particularly law enforcement, a great amount of leeway to make mistakes,” said Lin Wood, an Atlanta attorney who represented Richard Jewell, the former security guard who was an early suspect in the bombing at the 1996 Summer Olympics. “You have to show that there was almost an intentional act of wrongdoing.”

Jewell, who was publicly cleared by the FBI after a three-month investigation, sued several media outlets but not the government.

Wood said Hatfill could prevail, and should at least get a judicial determination of the appropriateness of the government’s investigative techniques.

Connolly, Hatfill’s lawyer, did not rule out further legal action, including suing members of the media.

Besides Ashcroft, Tuesday’s suit names Harp and two officials in the Justice Department’s domestic-preparedness office who contacted LSU. Harp, who recently retired from the FBI, could not be reached for comment.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.