Exploring the bond of brothers

- Share via

With all the recent breakthroughs in the field of genetics -- stem cells, cloning, mapping the human genome -- our society, which had formerly looked to environment, education and conditioning as formative influences, increasingly sees genes as the keys to human identity. We’ve all read stories about twins separated at birth and raised in different environments who both marry red-haired women named Enid, beget sons named Buster and have dachshunds named Fritz.

One salutary aspect of Saul Diskin’s memoir, “The End of the Twins,” is that it serves as a corrective to the current overvaluation of the determining role played by genes. At the same time, this poignant account of a deep and lasting relationship truly helps us understand what it is like to be a twin.

Here we read about a pair of identical twin brothers, growing up in the same New York Jewish family, eating the same food and playing the same games. As young men, both work on a merchant ship in the Caribbean and become enamored of Latin American culture. Yet one twin develops leukemia, while the other remains cancer-free and is able to donate some of his bone marrow.

Saul and Martin Diskin came into the world on the same day in 1934. The family, Jews of Eastern European descent, lived in Harlem, then the Bronx, then Brooklyn. Now a businessman living in Phoenix, Saul Diskin has clear recollections of his boyhood: favorite books, radio shows, stickball, childhood ailments and the neighborhood.

But his strongest memories have to do with his twin: “We could not read each other’s thoughts specifically, but we knew how the other was feeling, precisely. We knew the meaning of every gesture ... of every facial expression.... We were one person walking around in two little bodies.”

One of Saul’s most graphic memories is of him and his brother at age 5: Venturesome Marty dashes up several flights of stairs to the roof of the building where they live. Saul follows anxiously in his wake. On the roof, Marty blithely dangles over the parapet, waving, as his imaginative, apprehensive twin “sees” him fall to his death and is so terrified that he vomits. Martin, however, did not in fact fall, and it was Saul who had to be taken to the hospital to be fed through tubes. Two boys, same genes, same home, same neighborhood, yet in this respect utterly different.

By the age of 8, the boys had started on a long, conflict-riddled process of differentiating themselves from each other: Competitiveness, rivalry and fierce fights helped pave the way to separation and independence. They made different friends, developed different interests, attended different high schools. Martin, having served in the Army, took advantage of the GI Bill to pursue an advanced degree in cultural anthropology, which led to an academic appointment in New England. Saul became a real estate agent in Phoenix. Yet the deep bond of twin-ness was never entirely severed.

In the winter of 1970-71, Martin was diagnosed as suffering from chronic lymphatic leukemia. For 20 years, his disease was controlled by a combination of drugs, and he was able to lead a normal, indeed vigorous and productive life. Then, his illness took a sharp downturn, requiring more drastic treatment. Martin and his doctors began to consider the possibility of a bone marrow transplant. The process, as Saul Diskin recounts in grimly enthralling detail, was long and grueling. Not only did it involve extensive chemotherapy, radiation, surgery, debilitation, fear and anxiety, but it also took a tremendous amount of energy, initiative and planning by the patient and his family to get the best medical treatment, to persuade his medical plan to pay for it and his doctor to cede the case to a transplant specialist.

“In addition to being as well-versed in the medical aspects of his case as many nonspecialist doctors, [Marty] prepared himself very carefully to make the most persuasive case possible.... The strategy was to argue his case with crystalline logic and at the same time to make the doctor see that his life was at stake, without becoming strident or defeating him in argument.” The reader shares the Diskins’ elation at this victory, but what does it say about the state of American health care that a sick man should have to display the medical knowledge of a doctor, the tact of a diplomat and the skills of a trial lawyer to be granted a lifesaving operation?

Saul Diskin has written a vividly detailed, strongly affecting account of a family trying its best to cope with a protracted, life-threatening illness. He has also created a memorable portrait of a unique set of twins, their similarities, their differences and their continually evolving yet enduring relationship.

*

The End of the Twins

A Memoir of Losing a Brother

Saul Diskin

Overlook Press: 272 pages, $26.95

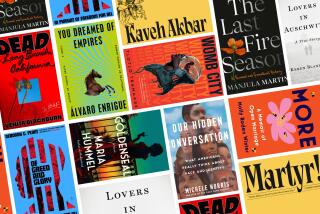

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.