Reading, ‘Riting and Rap

- Share via

So check it. On the white board in a Crenshaw High School classroom were the words: “Man vs. Ho.”

English teacher Patrick Camangian wrote the phrase to get his students talking about the lyrics by the late Tupac Shakur: “Blaze up, gettin’ with hos through my pager.”

It worked. A lively discussion ensued about sexism, racism and how degrading terms such as “ho” -- slang for whore -- can be used to dehumanize and divide people. In hip-hop terms, the students were feelin’ it.

Teachers nationwide are using rap -- the street-savvy, pop-locking, rhyming creations of Shakur, Geto Boys, Run-DMC and others -- to teach history and English. Some colleges are even training future educators to weave rap into high school lessons.

“In order for students to understand anyone else’s poetic language, they have to first understand their own,” Camangian said.

To some parents and teachers, the idea of mentioning Grandmaster Flash in the same breath as T.S. Eliot is wack. They reject the notion that rap, with its raw language and vivid depictions of violence, has anything in common with literature.

But those who use it to teach say rap can be intellectually provocative, shedding light on the grand themes of love, war and oppression in much the same way as classic fiction. As a teaching tool, they liken rap to the songs of Bob Dylan and Simon and Garfunkel, used by an earlier generation of teachers.

In Camangian’s South Los Angeles classroom on a recent afternoon, students read the lyrics from a Shakur song, “Shorty Wanna Be a Thug.” The verse describes a man’s internal struggle to remain virtuous while a devil-like figure tempts him toward immorality and loose women:

I tell you it’s a cold world, stay in school.

You tell me it’s a man’s world, play the rules

and fade fools, ‘n break rules until we major.

Blaze up, gettin’ with hos through my pager.

Camangian, 28, asked the class to compare the song to a speech said to have been delivered in Virginia in 1712 by a British slave owner. In the speech, whose authenticity has been questioned, Willie Lynch offers advice on preventing slave rebellions and urges that slaves be pitted against one another -- men versus women, light-skinned versus dark, young versus old.

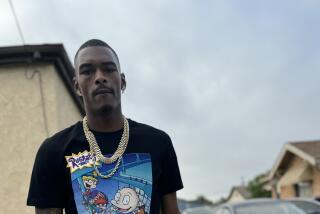

Toure Eagans, 16, said Shakur’s lyrics showed how the “slave mentality” persists in disrespectful language.

Shakur “is reinforcing what Willie Lynch said. He’s putting the man against the woman. It’s dehumanizing them,” he said.

“So it’s the same thing they did to the slaves? Take a powerful man and turn him into a slave?” Camangian asked.

Another student pointed out that some African American students address one another with racial epithets, without thinking about the pain such words can cause. “Yes, Willie Lynch said slavery will carry on for hundreds of years, and we still [perpetuate] it everyday in our language,” she said.

After class, Elyse Bryant, 16, said studying hip-hop helps students define a role for themselves in their neighborhoods and the wider world.

“We’ll sit in class and really think about what [rappers] are saying,” she said. “They talk about what’s going on in the country, from the government to the streets.”

The students also gain insight into how poetry is created. “When we go into college English classes, we’ll know how to break down each line,” she said. “You use the same skills to break down a college textbook that you use to break down lyrics.”

Lisa Moore, 16, said that hip-hop speaks directly to young people in a way that classic texts cannot.

“We need to learn about Shakespeare, but hip-hop is history too,” she said. “As far as Shakespeare goes, we can’t relate to that. We can relate to what’s going on now.”

Hip-hop has become an object of serious study on college campuses. Stanford University, the University of Connecticut, Michigan State University and Pennsylvania State University have offered classes on hip-hop. UC Berkeley has a poetry course devoted to Shakur’s work.

In high school and lower grades, hip-hop is a more delicate subject. Crenshaw Principal Isaac Hammond said some parents complained last year that their children had been exposed to foulmouthed rap lyrics in class. Hammond now requires Camangian to edit out the strongest language.

Shelby Steele, a research fellow at the Hoover Institution, a public policy center at Stanford, said: “I would be outraged to find out my child is being subjected to Tupac Shakur in an academic classroom.”

Steele, a political essayist who taught college English for nearly 25 years, said students learn rap lyrics on their own. In school, he said, “they need to be taught great literature.”

Two education professors -- Jeffrey Duncan-Andrade of UCLA and Ernest Morrell of Michigan State University -- say students need both.

The two designed and taught an English course at Oakland High School in which students studied rap lyrics in tandem with classic works. Duncan-Andrade and Morrell reported the results in July in the English Journal, published by the National Council of Teachers of English.

“Hip-hop can be used as a bridge linking the seemingly vast span between the streets and the world of academics,” they wrote. At the same time, they said, rap is literature, “a worthy subject of study in its own right.”

Duncan-Andrade and Morrell say rap lyrics can be used “to teach irony, tone, diction and point of view” and can be “analyzed for theme, motif, plot and character development.”

A sample lesson plan they offer to high school teachers calls for comparing “Kubla Khan,” by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, with “If I Ruled the World,” by rapper Nas; Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” with “The Message,” by Grandmaster Flash; and “Immigrants in Our Own Land,” by modern poet Jimmy Santiago Baca, with “The World is a Ghetto,” by Geto Boys.

Their students have noticed parallels between Eliot and Grandmaster Flash, the researchers wrote. Students found that both artists speak of a “wasteland” of physical and moral decay in their societies.

Nancy Brodsky, 23, a teacher at Samuel Gompers Vocational Technical High School in New York’s South Bronx, has her ninth-grade students listen to a song by Dead Prez before reading George Orwell’s 1945 fable “Animal Farm,” the classic commentary on the Russian Revolution.

The rap song “Animal in Man” is based on Orwell’s use of animals to represent figures such as Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin. In both works, a group of pigs seizes power on a farm and turns on the other animals. The creatures then revolt against the boss pig, Hannibal.

The last verse in the Dead Prez song says:

They took his tongue out of his mouth.

And cut his body up for sale, for real.

You better listen while you can.

It’s a very thin line between animal and man.

When Hannibal crossed the line, they all took a stand.

What would you have done? Shook his hand?

This is the animal in man.

Darien Lencl, 26, a social studies teacher at Skyline High School in Oakland, has made the Dead Prez song “Behind Enemy Lines” part of his students’ assigned reading on the civil rights and Black Power movements. The song deals with Fred Hampton, a 21-year-old Black Panther Party leader who was shot dead during a police raid in Chicago in 1969.

Outside class, students “may listen to the music and bob their heads, but they’re not going to think, ‘How does this relate to the lesson at hand and the curriculum we are using?’ ” Lencl said.

James Dickson, 23, a high school English teacher in Madison, Miss., uses “The Rose That Grew From Concrete,” a book of poems that Shakur wrote before he became a rap star.

The collection, which is devoid of obscenities, features verses about love, loneliness, his mother, death and the Black Panthers.

Dickson said he often compares Shakur’s poem “In the Depths of Solitude” to works by William Blake, the 18th century English poet, because both address how people struggle with internal conflicts.

Students first read Shakur’s poem, which includes this passage:

A young heart with an old soul

how can there be peace

how can I be in the depths of solitude

when there are two inside of me.

Then, Dickson said, they may better grasp Blake’s poem “Infant Sorrow”:

My mother groaned, my father wept;

Into the dangerous world I leapt,

Helpless, naked, piping loud,

Like a fiend hid in a cloud.

Struggling in my father’s hands,

Striving against my swaddling bands,

Bound and weary,

I thought best

To sulk upon my mother’s breast.

“When students see Tupac is writing about the same things that William Blake wrote about, it suddenly makes the poetry of these old, dead white guys much more accessible,” Dickson said.

Shakur, who was killed in a drive-by shooting in 1996, “was not a paragon of virtue, but neither was William Shakespeare,” said Dickson, adding that Shakespeare wrote about murder, rape and suicide.

Sometimes, violent events in the rap world intrude into the classroom. One morning last fall, teacher Cory Cofer, 28, announced to his fifth- and sixth-grade students at Jellick Elementary School in Rowland Heights that Jam Master Jay, a member of pioneering rap group Run-DMC, had been fatally shot in New York. The disc jockey, who was born Jason Mizell, was 37.

“He wasn’t a gangsta. He rapped about a lot of happy stuff,” said Cofer, who gives public readings of his own poetry under the name “Besskepp.”

After reading a newspaper article about the shooting to the class, one student said Jam Master Jay’s three children must feel sad.

Cofer tried to steer the lesson out of the gloom. “There’s a lot of positive hip-hop out there, and kids need to be exposed to it,” he said.

He introduced “Think Again,” a children’s book by rapper Doug E. Fresh, who became popular in the mid-1980s for his ability to beat-box, making drum- and bass-like noises with his mouth. One student, 11-year-old Issac, gave a brief rendition of beat-boxing.

Cofer read aloud the rap-rhymed tale about two boys, one black, one white, who don’t get along but eventually become friends. Cofer asked students what they thought of the lesson.

“It was tight!” Issac yelled.

*

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

Rap stands beside Whitman, Angelou

Education professors Ernest Morrell and Jeffrey Duncan-Andrade use hip-hop lyrics to deepen students’ understanding of established literary texts. Here are two sets of works that they asked students at Oakland High School to compare and contrast.

O Me! O Life!

Walt Whitman

O Me! O life! ... of the questions of these recurring;

Of the endless trains of the

faithless -- of cities fill’d with the foolish;

Of myself forever reproaching

myself, (for who more foolish than I, and who more faithless?)

Of eyes that vainly crave the light -- of the objects mean -- of the

struggle ever renew’d;

Of the poor results of all -- of the plodding and sordid crowds I see around me;

Of the empty and useless years of the rest -- with the rest me

intertwined;

The question, O me! So sad,

recurring -- What good amid these, O me, O life?

Answer.

That you are here -- that life exists, and identity;

That the powerful play goes on, and you will contribute a verse.

*

Don’t Believe the Hype

Public Enemy

(Excerpt)

Turn up the radio

They claim that I’m a criminal

By now I wonder how

Some people never know

The enemy could be their friend, guardian

I’m not a hooligan

I rock the party and

Clear all the madness, I’m not a racist

Preach to teach to all

‘Cause some they never had this

Number one, not born to run

About the gun ...

I wasn’t licensed to have one

The minute they see me, fear me

I’m the epitome -- a public enemy

Used, abused without clues

I refused to blow a fuse

They even had it on the news

Don’t believe the hype.

*

Still I Rise

Maya Angelou

(Excerpt)

You may write me down in history

With your bitter, twisted lies,

You may trod me in the very dirt

But still, like dust, I’ll rise.

Does my sassiness upset you?

Why are you beset with gloom?

‘Cause I walk like I’ve got oil wells

Pumping in my living room.

Just like moons and like suns

With the certainty of tides,

Just like hopes springing high,

Still I’ll rise.

Did you want to see me broken?

Bowed head and lowered eyes?

Shoulders falling down like

teardrops,

Weakened by my soulful cries?

Does my haughtiness offend you?

Don’t you take it awful hard

‘Cause I laugh like I’ve got gold mines

Diggin’ in my own backyard.

You may shoot me with your words,

You may cut me with your eyes,

You may kill me with your

hatefulness,

But still, like air, I’ll rise.

*

Cell Therapy

Goodie Mob

(Excerpt)

Me and my family moved in our apartment complex

A gate with the serial code was put up next

They claim that this community is so drug-free

But it don’t look that way to me ‘cause I can see

The young bloods hanging out at the sto 24/7

Junkies lookin’, got a hit of the blow, it’s powerful

Oh, you know what else they tryin’ to do

Make a curfew especially for me and you,

The traces of the New World Order

Time is getting shorter, if we don’t get prepared

People it’s gone be a slaughter

My mind won’t allow me to not be curious

My folks don’t understand so they don’t take it serious

But every now and then I wonder

If the gate was put up to keep crime out or to keep our ass in.

Los Angeles Times

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.