Five Points’ blunt history

- Share via

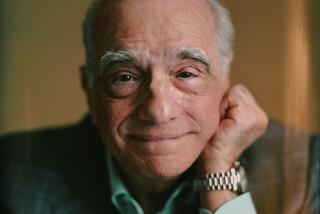

Martin Scorsese’s new film, “Gangs of New York,” has positioned the director as the best-known chronicler of the infamous 19th century slum called the Five Points. But 160 years before Scorsese’s vision became a mega-budget, mega-star Hollywood epic, another visionary artist took the measure of the lower Manhattan neighborhood.

If the filmmaker’s interpretation of events seems like noirish hyperbole, it does not compare with the version offered in 1842 by Charles Dickens.

“This is the place: these narrow ways, diverging to the right and left, and reeking everywhere with dirt and filth,” wrote Dickens of his police-escorted visit to the Five Points. “Debauchery has made the very houses prematurely old. See how the rotten beams are tumbling down, and how the patched and broken windows seem to scowl dimly, like eyes that have been hurt in drunken frays.”

Offering a grim epitaph for the neighborhood, Dickens added, “all that is loathsome, drooping, and decayed is here.”

That the Five Points -- located in what is now Chinatown -- was a den of violence, crime and various forms of social, moral and spiritual dissipation is beyond debate. Its story is a century long. But out of necessity, Scorsese’s film contracts decades of history into less than three hours of screen time. The actual story of the Five Points is, of course, much murkier and more complicated.

Scorsese did not strive to create a work of historical scholarship, but he did seek a sense of authenticity. He drew his inspiration from Herbert Asbury’s 1928 book, also titled “Gangs of New York,” and sent a copy of the “Gangs” screenplay to historian Tyler Anbinder, author of “Five Points: The Nineteenth-Century New York City Neighborhood That Invented Tap Dancing, Stole Elections and Became the World’s Most Notorious Slum.”

“For almost everything I pointed out,” says Anbinder, “[Scorsese] would say, ‘Well, to make this work dramatically we’ve got to make things that happened at different times happen at the same time in the film. We’ve got to make things that happened to different people happen to the same person.’

“The events in the movie are almost all based on reality,” says Anbinder, “but almost none of them happened the way they appear.”

The Five Points area was so known because it was bordered by the five-pointed intersection of three downtown streets, Orange, Anthony and Cross. (The streets have since been renamed Baxter, Worth and Mosco.) Because the neighborhood was built in what was then considered a geographically undesirable area -- it sat on top of a drained pond that had once supplied part of the city with drinking water -- it drew mostly downtrodden and destitute newcomers.

Conceding to, and fleeing from, the area’s increasingly downscale demographics, families, businesses and craftsmen began to leave the Five Points in the 1820s.

By the middle of the 19th century, the Five Points had become a hub of squalor and transgression.

Much of the tangible evidence of what life was like in the Five Points was lost on Sept. 11; nearly a million items uncovered in an archeological excavation in the early 1990s were destroyed when their downtown storage facility collapsed beneath the World Trade Center.

But the neighborhood has always been more about legend and folklore than discernible fact, and that, Anbinder says, is what’s reflected best in Scorsese’s film.

“I think by far the most important thing is the overall theme of, ‘This is how America was made,’ ” Anbinder says. “He gets that exactly right.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.