Camp David Trip Is a Milestone for Musharraf

- Share via

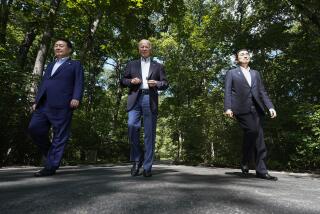

NEW DELHI — Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf’s visit to Camp David today as the guest of President Bush will mark the culmination of a remarkable change in political fortune.

Four years ago Washington was watching with alarm after Gen. Musharraf seized power in a coup. Now he is the first South Asian leader to be favored with an invitation to the presidential retreat, a compliment reserved for special allies. That journey owes much to Musharraf’s embrace of America’s war against terror after Sept. 11.

The invitation puts the seal on Bush’s determination to overlook past concerns, reward Musharraf for his support in the fight against the Al Qaeda network, and prod him to do more.

Pakistan’s nuclear rival, India, with its democratic tradition, huge market and embrace of technology and globalization, would seem at first glance the more natural long-term U.S. partner in the region. But Pakistan is important to the Bush administration’s primary immediate objective: eliminating Al Qaeda and controlling international terrorism. The U.S. is engaging with both countries, while trying to push them along a suspicion-filled path to peace.

Pakistan’s Foreign Office spokesman, Masud Khan, said the Camp David visit would bind Pakistan and America in a long-term strategic relationship. Restoring military ties between the two countries and urging the U.S. to pressure India to settle the dispute with Pakistan over the Kashmir region will top Musharraf’s agenda, Khan said in a telephone interview.

Since he seized power in 1999, Musharraf has taken limited steps toward democracy. Parliamentary elections last year were criticized by a European Union team of observers, which found that the military manipulated the polling. In North-West Frontier Province, voters elected a radical Islamic administration that recently introduced Sharia, or Islamic law. Radicals there began tearing down posters of women, a move that Musharraf last week criticized as embracing the values of the hard-line Taliban that ruled Afghanistan before the U.S.-led war there.

For Washington, the nightmare scenario in Pakistan would be the emergence of a radical Islamic state with nuclear weapons, at present not a likely outcome.

To the United States, Musharraf represents a bulwark against extremism. After Sept. 11, he joined the war against terrorism and banned some militant groups, and Pakistani authorities arrested numerous Al Qaeda figures, some of whom were handed over to the U.S.

Musharraf also claims to have clamped down on militants seeking to enter the Indian-controlled portion of Kashmir -- the main Indian precondition for peace talks on the territory.

In Muzaffarabad, the capital of Pakistan’s portion of Kashmir, the offices of many militant Kashmiri organizations have been closed or moved and their phones disconnected. Local authorities said militants’ training camps had also been shut down on Musharraf’s orders.

Indian authorities contest that. Deputy Prime Minister Lal Krishna Advani, who met with Bush and British Prime Minister Tony Blair last week, recently described Pakistan as an “epicenter of terrorism.”

The rhetoric over Kashmir has grown more heated in recent days, with both Advani and Musharraf visiting Washington and London.

In return for Pakistan’s support of the war against terror, Musharraf will reportedly be looking for financial aid or debt write-offs and access to military equipment.

In London, the Pakistani leader warned last week that his country would be forced to rely on its nuclear arsenal as its only military deterrent if India was allowed to procure weapons while U.S. sanctions prevented arms sales to Pakistan. That would create a dangerous imbalance, he said. The heart of the conflict between India and Pakistan, and a key to stability in the region, is Kashmir. In April, Indian Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee offered to extend the “hand of friendship” to Pakistan if it closed down militants’ bases in Pakistani-controlled Kashmir and prevented incursions to the Indian side.

Since then, each side has demanded that the other take more concrete steps toward peace, and both expect the U.S. to pressure the other side to that end. New Delhi-based political columnist Praful Bidwai believes the Camp David meeting will lead to more pressure on India to negotiate on Kashmir.

“India has to show its willingness to put Kashmir on the negotiating table,” he said. “I think Pakistan is terribly mistaken in using violence and these militant groups, but their grievance is genuine. For 30 years there has been no discussion” on the territory. But Ajai Sahni of the Institute for Conflict Management in New Delhi, who opposes any peace deal that would concede any part of Kashmir, characterizes the recent thaw and the hard-line rhetoric that preceded it as “transient diplomatic maneuvers” designed to sway world opinion.

“The India and Pakistan relationship has not changed one iota in the past five years,” he said. “It’s not a quarrel over a piece of land. The conflict in Kashmir is an ideological conflict between India’s secular democracy and Pakistan’s exclusionary Islamic state structure. This conflict cannot end until one or the other of the two ideologies is abandoned.”

*

Special correspondent Mubashir Zaidi contributed to this report from Islamabad, Pakistan.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.