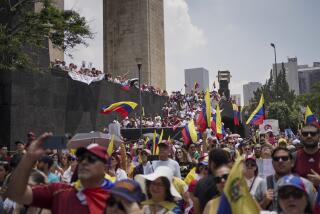

Protest Swelling in Bolivian Plaza

- Share via

LA PAZ, Bolivia — At the very center of this capital city, groups of Aymara and Quechua Indians have taken over the plaza the Spanish conquistadors first laid out in 1548, cutting up cobblestones the size of bread loaves to make barricades, filling the days with fervent speeches about revolution.

They’ve been there for four days, the focal point of an uprising that has shut down this metropolis of 1.5 million people, where cars no longer circulate, stores no longer open and children while away the hours playing soccer on usually bustling boulevards and highways.

The Aymara and Quechua have walked down into La Paz from the slums known as “the periphery” that cling to the ragged brown mountains surrounding the city. Thousands more have marched for days from distant towns and villages, turning this country’s centuries-old social order upside down.

“Before, we let other people speak for us,” said German Jimenez, a teacher and Quechua from the city of Potosi who arrived in La Paz on Wednesday after hitching rides on tractors, walking and bicycling hundreds of miles over six days. “Now we say the original [Indian] nations are ready to rule our own affairs. We are ready to impose our own democracy.”

The Aymara and Quechua make up the vast majority of the protesters demanding that President Gonzalo Sanchez de Lozada step down after a year of political upheaval and violence that has left more than 150 people dead. They say that his administration is corrupt and venal and that it has only worsened life for Bolivia’s already-poor Indian majority.

The nation’s leading Indian and peasant leaders are also calling for a constituent assembly that would rewrite the constitution and wrest control of the country from the white and mixed-race minority that has ruled this region since the Spanish conquest.

“It’s the poorest villages that are rising up, all over the western part of the country,” said Clemente Macias, a 32-year-old construction worker from La Paz, referring to Bolivia’s Aymara and Quechua heartland.

On Wednesday, the army and police once again in effect surrendered La Paz to the protesters, even as violent demonstrations swept through other Bolivian cities, leaving two more people dead and the president’s future more in doubt.

Army troops and protesters clashed in Patacamaya, about 60 miles south of La Paz, and in the cities of Oruro and Cochabamba. Human rights activists launched a hunger strike in a La Paz church, demanding the president step down.

Huddled in his residence in La Paz’s affluent southern neighborhood, Sanchez de Lozada met with advisors and allies but issued no statements.

With official information scarce, La Paz was awash in rumors about American military advisors, weapons arriving on an airplane from Miami, and newspapers and television stations being harassed for broadcasting reports critical of the government.

“If we go off the air it will only be because we have been taken over by the government,” said a breathless newscaster at Channel 13, a university station. “All we have been doing is showing what the people are clamoring for.”

Hours later, the station was still broadcasting.

Appointed president last year by Congress after an election in which he won 22% of the vote, Sanchez de Lozada has vowed not to step down, calling the protesters “subversives” who are manipulated by outside forces.

A tight cordon of soldiers blocked all the approaches to the downtown presidential palace, just two blocks from the protesters’ barricades at the Plaza San Francisco.

But they allowed about 1,000 miners and several other groups to march through the city center without incident.

Eduardo Dalence, a professor at the University of El Alto, walked with the miners as they entered the city.

“Step back, they’re going to set off some dynamite,” he told some people on the sidewalk watching the marchers. “Don’t worry, it’s just a little.”

Seconds later, an explosion rocked the street, setting off an alarm inside an office building. Later, a group of peasants arrived from the Yungas coca-growing region hundreds of miles east of La Paz.

Many were armed with sticks and pieces of rebar, their faces sunburned and weather-beaten after days of marching.

For Juan Carlos Alfaro Monroy, one of about a thousand demonstrators milling about the plaza Wednesday morning, each contingent of marchers that arrived was a victory.

“This is the reaction of all the people who have been excluded,” he said. “Look up at those mountains where we live. None of us have any gas connections. But all these hotels and office buildings around us do.”

Moments later, three station wagons passed, each carrying two coffins on its roof.

“Look, look!” several people shouted. The coffins, they said, held people shot by the army in the protests. “See how they’re killing us.”

Nearby, men tore up the plaza’s storm drains, creating a ditch that would prevent any car from passing.

The city’s international airport has been closed since Sunday because of the disturbances and uprisings in the La Paz suburb of El Alto, home to about 750,000 Aymaras and Quechuas.

Residents of El Alto and other “periphery” communities have covered the highways leading to the airport with a moonscape of stones.

On Tuesday, as a small group of foreign journalists entered La Paz on bicycles, women and children worked to add more stones to the barricades, carrying one at a time, creating a clutter of rocks that stopped army trucks, tourist vans and most other vehicles.

The airport remained closed to most commercial traffic, as did nearly all the roads leading into the city, something that has led to food and fuel shortages.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.