The deadly threat of sepsis

- Share via

It was the second semester of his freshman year at Salve Regina University in Newport, R.I., and John Kach, then 18 and a member of the basketball team, was in great shape.

One night he developed a fever of 105 and flu-like symptoms. His girlfriend wanted to take him to the hospital, but he said no.

As Kach says of the illness that struck him in 2000: “A guy’s not going to go to the hospital for a high fever.” But by 5 a.m., he was fading in and out of consciousness. By the time they got to the hospital, he could barely breathe. The pain in his back was excruciating as his kidneys shut down. His white-blood cell counts were sky-high -- like his fever, a sign of rampant infection.

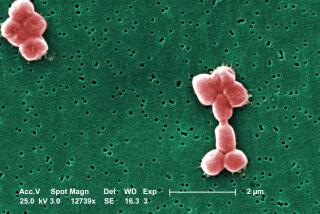

Kach had bacterial meningitis, and it was rapidly turning into severe sepsis. A reaction to infection, sepsis causes runaway inflammation, blood clots and organ damage in 750,000 Americans every year, killing an estimated 215,000.

Kach’s circulation became so poor he developed gangrene. Doctors had to amputate his right leg below the knee, part of his left foot and all of his fingers. (This summer, because of nerve damage, he had the other leg amputated below the knee.) He needed dialysis because of his failing kidneys. His heart was pumping so hard his bed shook. But he lived.

Many others don’t. Even in the best hospitals, sepsis can rapidly become fatal, as one organ after another shuts down.

According to a report earlier this month in the Journal of the American Medical Assn., sepsis following surgery is the most common medical “injury” in hospitalized patients. Sepsis is associated with the greatest increases in length of stay, costs (on average, $57,727) and in-hospital deaths.

Sepsis is the second-leading cause of death in non-coronary intensive-care units and the 10th-leading cause of death overall in the U.S., according to researchers from Atlanta’s Emory University and the National Center for Environmental Health, writing in the April issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

Current estimates of the incidence of sepsis may actually be low. A person with a gunshot wound may die from sepsis after two weeks in the hospital. But the death certificate will say only gunshot injury, not sepsis, notes Dr. Howard Belzberg, associate director of trauma/critical care at Los Angeles’ County-USC Medical Center.

In the past, doctors couldn’t even agree on what sepsis was because it so complex.

Now they not only have defined its stages precisely but, more important, know better how to treat each step of the process.

Sepsis is an inflammatory response that can include abnormal clotting and bleeding in the presence of infection. Septicemia, also known as blood poisoning, is sepsis that begins with a blood-borne infection. Severe sepsis is sepsis with organ dysfunction. Septic shock is severe sepsis in which the cardiovascular system fails, blood pressure drops and organs are deprived of blood.

Septic problems can begin with infection anywhere in the body. As soon as the immune system detects infection, it starts pumping out white blood cells that secrete chemicals called cytokines.

Some of these (such as interleukin-1, interleukin-6, interleukin-8 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha) keep the aggressive immune response going. Others (such as interleukin-1 receptor antagonists, interleukin-10 and soluble tumor necrosis factor receptors) do the opposite -- they damp down the inflammatory response.

In the early stages, the correct antibiotic may halt sepsis. But often, the inflammatory response spirals out of control, revving up the whole body -- raising fever and increasing white blood cells, respiration, cardiac output and heart rate.

This “overexuberant” response soon begins destroying tissue, says Dr. Mitchell Levy, director of the medical intensive care unit at Rhode Island Hospital, a teaching hospital of Brown University.

In the lungs, cytokines trigger chemicals that damage delicate air sacs. They make blood vessels leaky, allowing fluid to leak into the lungs, kidneys and other tissues. As blood vessels dilate and leak, blood pressure drops, forcing the heart to beat faster.

Thanks to a series of recent studies, doctors now have a much more precise idea of how to use ventilators (breathing machines) so as not to further destroy lung tissue; this can reduce death by 9% in patients with sepsis who also have acute respiratory distress syndrome.

They can reduce death by 15% to 20% by giving steroids (which dampen immune response) at lower doses for longer periods. And doctors are armed with better antibiotics too, including Linezolid for streptococcus and Capsofungin for fungal infections.

But perhaps the most excitement -- and controversy -- centers around the anti-sepsis drug Xigris (drotrecogin). Made by Eli Lilly & Co. (which is co-sponsoring a campaign to raise awareness of sepsis), the drug can reduce the death rate by 6%, though it can also cause abnormal bleeding. Xigris is an activated form of a chemical called protein C.

But Xigris is so expensive -- nearly $7,000 for a several-day treatment -- that some hospitals now ration it, and sales have not met what the company calls the initial “high expectations” of two years ago, when the drug was approved.

That translates to a situation in which many septic patients still die because they don’t get state-of-the-art care. Doctors probably use up-to-date sepsis therapy only 10% to 40% of the time, says Dr. Peter Provonost, associate professor of anesthesiology and critical care medicine at Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.

John Kach is thrilled to count himself among the survivors. If his girlfriend hadn’t rushed him to the hospital, he says, “I would probably have died in my bed.”