Breeding only the best

- Share via

How is it that the once obscure history of eugenics -- the pseudoscientific belief in the biological origins of social success and failure -- has become a hot topic for academics, reporters and investigative journalists? Any story that involves a combustible mix of reproduction, race and class is bound to spark attention, but there’s more going on here than intellectual prurience.

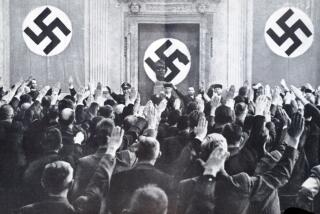

First, there’s the specter of reparations looming over recent grass-roots efforts to wring public apologies from various state governments for their role in compelling patients and the “socially unfit” to undergo forced sterilization during the first half of the 20th century. “Our hearts are heavy for the pain caused by eugenics,” noted Gov. Gray Davis in March, acknowledging that the victimization of some 20,000 people in state hospitals marked “a sad and regrettable chapter” in California’s history. In the 1920s, the Golden State’s leading civic reformers -- including Sacramento banker Charles M. Goethe, Nobel Prize-winning physicist Robert Millikan and real estate tycoon Ezra S. Gosney -- lobbied nationwide for the eugenics agenda. And in the 1930s, as board members of Pasadena’s Human Betterment Foundation, they enjoyed a mutually appreciative relationship with the advocates of “race hygiene” in Nazi Germany.

Then there are the cautionary lessons the past offers about the unregulated use of genetic engineering and reproductive technology. Such contemporary issues as pre-implantation genetic diagnosis, gene therapy and reproductive and research cloning promise the same kind of moral and political quagmires as sterilization, birth control and immigrant screening did in the United States between the world wars. Similarly, our current interest in the biological roots of cognitive ability echoes early 20th century debates about IQ tests.

Public concern today is directed not only at the reliability of research and the dangers posed by scientists going into the business of social engineering but also at how market forces drive the new genetics. As biotech companies take the initiative in research and development, who will get to decide, for example, whether prospective parents can customize their babies or whose identities should be maintained in DNA databanks?

In the eugenics movement of the 1920s and 1930s, enterprising academics and professionals, backed by government support and corporate philanthropy (W. Averell Harriman, Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller Jr.), led the campaign for “human betterment” through applied biology. Their expertise determined, for example, which unmarried, sexually active women and “feebleminded” adolescents should be sterilized. But, as demonstrated in these two very different books -- Nancy Ordover’s theoretical monograph “American Eugenics” and Edwin Black’s “War Against the Weak,” a muckraking history -- eugenics was much more than a short-lived, crackpot crusade.

Ten years ago the historical literature on eugenics was sparse, with the foundational studies of Mark Haller’s “Eugenics” (1963) and Daniel Kevles’ “In the Name of Eugenics” (1985) providing our basic knowledge of its rise and fall. More recently, feminist historians -- including Laura Briggs, Angela Davis, Linda Gordon, Wendy Kline, Regina Kunzel and Alexandra Minna Stern -- have deepened our understanding about the scope and cultural significance of eugenics as a site of struggle over the politics of reproduction and race. As a contribution to this genre, “American Eugenics” explores governmental attempts to use eugenics to impose “technological fixes” on the underclass “in lieu of meaningful correctives to economic inequity.”

Ordover, who is a Rockefeller fellow in the Program for the Study of Sexuality, Gender, Health and Human Rights at Columbia University, is less interested in eugenics as public policy or science than in its “extremely nimble ideology.” In this compact, far-ranging cultural critique, she invites us to make connections between anti-immigrant panics, sterilization campaigns and the search for the genetic roots of sexual desire. Eugenics, she argues, is like a “scavenger” that collects and exploits anxieties about national identity, consigning the politically disenfranchised to the garbage dump. It uses the value-free language of “science” and “public health” to mask its political agenda: “[W]herever biologism and public policy have intersected, they have extracted a terrible price from the poor, physically and politically.” Ordover’s conclusion is certainly true for the hundreds of thousands of mostly poor women who, before World War II, were required to acquiesce to sterilization to gain release from mental hospitals, homes for the feebleminded and other such institutions, and who in the 1950s and ‘60s were tricked or coerced by social and public health workers into sterilization or untested birth control regimens as a condition for receiving public assistance.

Missing from Ordover’s study is any sense of what this experience was like for its victims. The problem for historians is getting around the reluctance of public bureaucrats to open their files to scrutiny, especially given their concern about the slippery slope from symbolic contrition to compensatory lawsuits. In Canada, the government of Alberta recently settled for $55 million with mentally ill patients who had been sterilized between 1928 and 1972; in Sweden, the government paid $21,250 to each person unlawfully sterilized between 1941 and 1975.

So we should be grateful to the authors of “Against Their Will: North Carolina’s Sterilization Program” -- Kevin Begos, Danielle Deaver, John Railey, Ted Richardson and Scott Sexton -- writing in the Winston-Salem Journal, for achieving what has eluded academics: giving voice to those who have been hidden from history. In a model of investigative journalism, “Against Their Will” (available through the newspaper’s Web site, against theirwill.journalnow.com, or by mail for $2) brings us heartbreaking stories from some of the 7,600 mostly African American women in North Carolina whose forced sterilization left enduring emotional scars. “Why didn’t they just sew me up, just sew me up period,” asks one woman, 35 years after she was sterilized at age 14. “Contrary to common belief,” writes Begos, “many of the thousands marked for sterilization were ordinary citizens, many of them young women guilty of nothing worse than engaging in premarital sex.” In addition to personal testimony, the Journal’s hard-hitting five-day series names those responsible for this gross misuse of state power, including the state’s medical school, political and philanthropic leaders -- and even the newspaper itself (known then as the Winston-Salem Journal & Sentinel), which endorsed and promoted North Carolina’s eugenics program. “The danger is in the moron group,” one 1948 story warned. “Among other things, they breed like mink.”

“War Against the Weak” is a much more ambitious undertaking. Edwin Black is on a mission to disclose “many explosive revelations and embarrassing episodes about some of our society’s most honored individuals and institutions....” His pitch may be sensational and the prose occasionally purple, but he’s written a serious, thoroughly documented study. The scope of the book is impressive -- it spans 150 years and reaches into the archives of four countries -- and it contains some remarkable new data and sharp insights. But “War Against the Weak” promises more than it delivers and has a tendency to exaggerate its own importance.

Black has the right credentials to “tear away the thickets of mystery surrounding the eugenics movement around the world.” An experienced Holocaust investigator and journalist, he has written two books on related topics: “The Transfer Agreement” (1984), which explored the pact between the Third Reich and Jewish Palestine, and “IBM and the Holocaust” (2001), an expose of how the corporate pioneer in data processing helped Hitler’s Germany run its trains on time. The author brings a critical sensibility to his work, morally anchored in his parents’ harrowing escape from the Nazis.

As with his previous books, Black recruited a large team of researchers and consultants, mostly volunteers, who assembled roughly 50,000 documents. “I functioned as a traffic cop, managing editor and travel coordinator,” he writes of the logistical complexities of the project. As a result, the book is richly detailed, with examples of eugenic initiatives from all over the United States. Black has surprisingly little to say about California, despite acknowledging that it “led the nation in sterilization and provided the most scientific support for Hitler’s regime.”

Black imposes a strong point of view on his chronological narrative, which is driven by two major arguments. First, he proposes that eugenics in the United States was a prestigious enterprise -- bankrolled by big business, studied in the finest universities and embraced by the professions. He aims his populist fire at the “alliance between biological racism and mighty American power, position and wealth,” which he sees as having been united for one purpose: the creation of “a superior Nordic race.” This is not an original argument -- for example, see Elof Axel Carlson’s “The Unfit” (2001) -- but Black provides new kinds of damning evidence about “corporate philanthropy gone wild.” He shows how the eugenics movement of the 1920s and ‘30s actively lobbied for “overseas eugenic screening,” anti-miscegenation legislation, and the sterilization of people suffering from a variety of physical disabilities, not all of them heritable, including blindness. Moreover, as Black notes, “the idea of sending the unfit into lethal chambers was regularly bandied about” in American eugenic circles long before the Nazis murdered 100,000 mental patients.

Black’s second argument is that “[i]n eugenics, the United States led and Germany followed.” We know from previous studies -- in particular, Stefan Kuhl’s “The Nazi Connection” (1994) and Benno Muller-Hill’s “Murderous Science” (1998) -- that there was a great deal of collaboration between Nazi and American “racial scientists.” But Black goes further, asserting that the “scientific rationales that drove killer doctors at Auschwitz were first concocted at the Carnegie Institution’s eugenic enterprise” at Cold Spring Harbor, Long Island. Eugenics, claims Black, “infected our society and then reached across the world and right into Nazi Germany.” Later he backtracks, observing that Hitler did not develop his racist and anti-Semitic views “from anything he read or heard from America.”

“War Against the Weak” also asserts that until the United States entered the war, the Nazi regime’s “eugenical courts, mass sterilization mills, concentration camps, and virulent biological anti-Semitism ... enjoyed the open approval of leading American eugenicists and their institutions.” This may have been true, but Black doesn’t have the evidence to back up his claim. Moreover, he doesn’t need to pile on the hyperbole when he’s dug up so many compelling examples of the love affair between American eugenicists and German race scientists: for example, that Corporal Hitler read his favorite American eugenicists while in jail in 1924 and later sent a fan letter to Madison Grant, author of “The Passing of the Great Race”; or the strange case of Edwin Katzen-Ellenbogen, a Jewish psychiatrist, eugenicist and naturalized American citizen, who was found guilty by the Nuremberg tribunal for committing war crimes in Buchenwald.

Black’s relentless focus on the Nazi connection means that he pays little attention to other thorny issues, such as why important segments of the left (Fabian socialists, Progressive reformers and feminist activists, for example) from time to time joined forces with right-wing moralists on matters relating to eugenic reproduction. Witness, for example, the successful courting of Margaret Sanger by leading eugenics groups in the 1930s. Black minimizes the extent to which the battle between leftists, moderates and rightists has often been fought within as well as over eugenics.

“War Against the Weak” might as well end in 1945, because it skips over the last half century in about 20 pages. After World War II and the demise of the Nazi regime, Black loses interest. This leads to some lazy, facile predictions of the withering away of “racist ideology and group prejudice” and an assertion that from the 1960s to the 1980s “the racist old guard of eugenics and human genetics died out, bequeathing its science to a new and enlightened generation of men and women.” He concludes on an appropriate note of caution, warning of the dangers that lurk in our “precocious new genetic age,” when “people are once again defined and divided by their genetic identities.” But, again, he’s too quick to reduce complex issues to one root cause. Next time around, he says, “[i]f there is a new war against the weak it will not be about color, but about money.” Can’t we expect, though, that existing social inequalities will figure prominently in decisions about who will be able to pay for the genetic enhancement of future generations? And isn’t “The Bell Curve” (1994) -- Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray’s influential, pseudoscientific search for genetic explanations of racial inequality -- essentially a eugenics tract?

As Nancy Ordover suggests, issues of race and gender, operating within and not apart from economics, were very much evident after World War II, when eugenics reinvented itself, first in population control and later in sociobiology. Now, with muscular conservatives throwing their weight around in Washington, D.C., and economic inequality returning to levels reminiscent of the Gilded Age, it is not surprising that restricting the birthrate of the poor is a mainstay of the administration’s welfare policy.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.