Immigrants’ friend lives life of grace

- Share via

NEW YORK — Orlando Tobon’s business sits in a mini-mall in the shadow of the Roosevelt Avenue el in Jackson Heights, with barely enough room for two desks, two phones and a fax machine. But his shop, Orlando Travel, never lacks for customers.

No surprise there, considering Tobon, 58, often declines to charge customers for his assistance. Lifting the spirits and chances of Spanish-speaking immigrants, he ladles out suggestions on where to look for a job, an apartment or an immigration lawyer, or how to respond to a parking ticket, an eviction notice or even a supervisor’s sexual advances.

A travel agent and accountant by profession, Tobon asks for just $40 to complete federal and state tax returns and is known for figuring out the cheapest, if more circuitous, ways to Latin America.

He is chubby and mustachioed, sweet-voiced and graceful, even dainty, his salt-and-pepper hair slightly askew. He is affectionately called “the mayor of Little Colombia.”

At his core, Tobon says, he’s not out to get rich but rather to drum up charity for fellow Colombians in need. As Arturo Sanchez, a friend and immigrant-studies expert, puts it, Tobon is “a classic immigrant broker,” an intermediary between two cultures, Colombia’s and the United States’, with the twist of being a conspicuously generous man too.

“I sleep well at night,” Tobon said, with four or five sets of donated crutches -- slated to be mailed to Colombian hospitals -- awaiting his attention off to one side. “All my life I do this type of thing for others because my mother taught me to help people, and even my grandfather was doing this.”

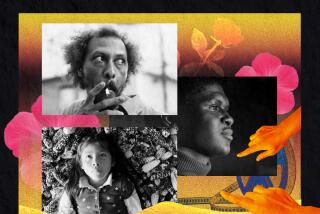

Tobon is likely to gain a much larger following in his adopted city: Though not an actor, he plays Don Fernando, a character based on himself, in “Maria Full of Grace,” an HBO-financed fictional film distributed by Fine Line Features that opened July 16 in L.A. and New York and expands into other cities Friday.

Joshua Marston, writer and director of the low-budget ($3 million) “Maria Full of Grace,” thought he had wrapped up his writing of the screenplay -- about a beautiful young woman enticed into transporting drugs inside her stomach in a misguided attempt to break free from her dead-end Colombia factory job -- when an acquaintance of Marston’s suggested he meet Tobon.

Marston, 35, who lives in Brooklyn, managed to pull Tobon away from his office long enough to hear his history of, among other things, raising impromptu donations to send the bodies of unlucky drug swallowers home to Colombia for burial. Another of his nicknames is “the angel of death.”

Marston was so taken by Tobon’s stories, and by his automatic credibility in soliciting donations from his patrons, that he rewrote the screenplay, deciding Tobon was one of a kind and should play himself in the film, several scenes of which were shot in Jackson Heights.

“What’s so impressive about Orlando is he represents something that works against the notion of New York as this bad, cold place,” Marston said. “He’s a centerpoint of reassurance, communication and all types of help for immigrants. He is a living testament to the ways that immigrants survive and build a new life here.”

*

Lured by ’64 World’s Fair

Tobon moved to New York 40 years ago, drawn by the World’s Fair. He found an apartment in the back of a Roosevelt Avenue building in Sunnyside and a job at an Italian catering hall nearby. He later went to work at the old Swingline Staple factory in Long Island City.

After earning a degree and license as an accountant at LaGuardia Community College, across from the factory, Tobon got married, in 1975, only to divorce three years later. He remained a bachelor until earlier this year, when he married a divorcee in Colombia; she and her teenage daughter will move into his Jackson Heights apartment later this summer.

Although he has no children himself, he refers to his sister’s three, all grown, as his own. Their photos hang on the cluttered walls of his storefront alongside pictures of Latin singing greats, such as the late Celia Cruz, and political bigwigs with whom he has rubbed shoulders -- Bill and Hillary Clinton, Rudy Giuliani.

Tobon’s life has also been marred by tragedy. His mother died on his birthday in the 1990 Avianca Flight 52 jet crash, returning from a trip to take food and clothing to poor people in Colombia.

Bound for Kennedy Airport, the plane ran out of fuel while awaiting clearance to land in rain and fog. It crashed into a hillside in Cove Neck on Long Island, killing 73 of the 158 on board. Tobon had booked 16 other passengers on the flight.

Federal investigators cited poor pilot performance as the cause of the crash. Tobon’s family received $50,000 in compensation -- “peanuts,” he said.

It was a car crash in the early 1980s that led to his one-of-a-kind involvement with drug mules who die, he said.

On that occasion, the sister of the wreck’s teenage casualty asked for his help to send the victim’s body home to Colombia. “We went over to the city morgue in Jamaica, and I’ll never forget the kindness that was shown to us that day by the African American lady who worked there,” he recalled.

“I barely spoke English, but she helped me a lot, and, as I left, she gave me a kiss.

“ ‘This dead girl,’ she said to me, ‘she is very lucky.’

“ ‘Why?’ I asked.

“ ‘I have three or four bodies here, drug mules, and nobody claimed them.’ ”

Those dead teens were Colombians, and Tobon got involved for them too.

He remembers he was able to help identify one boy and paid, with donations, to have him sent home for his funeral. The others were laid to rest in a potter’s field on Hart’s Island.

In “Maria Full of Grace,” one character notes that it takes just one leak in a swallowed packet of powdered heroin or cocaine -- out of as many as 100 ingested per plane trip, each packet pressed into the snipped-off finger of a surgical glove and tied shut -- to cause a drug mule’s death. But mules can receive as much as $10,000 a trip, more than several years’ worth of honest wages.

It’s only after one of the mules in the film meets her grisly end that Tobon’s character enters the story. The character, Don Fernando, uses contacts in a New Jersey police department to trace the victim’s identity.

*

Immigrant experience

In New York City, the Colombian immigrant community has grown to 107,000 since the earliest immigration wave that included Tobon, according to the 2000 federal census.

Segundo Pantoja, director of the Center for Ethnic Studies at Borough of Manhattan Community College, said that from the 1960s to 1980s, Colombians moving to the city tended to be poor and uneducated.

Theirs was a classic narrative, he says. The first generation took bottom-rung jobs, lived in substandard housing and weathered the psychic pain of living far from their culture and families to plant seeds of a better life for their children.

Pantoja says those children, now adults, have done better than their parents, with many entering the middle class, and this second generation has been joined by more recent arrivals who touch down with backgrounds as doctors, lawyers and architects. They were catapulted out of Colombia not by poverty but by its guerrilla violence and governmental volatility.

“We are a very diverse group, with a U.S.-based population of 1.1 million,” said Pantoja, who emigrated from Colombia in the early 1980s. “Only a very tiny percentage get involved in the illegal business of drugs.”

Tobon confronts immigrants’ immediate concerns, whatever comes through his door. Characteristically, he makes no exceptions for those who died trying to make a better life for themselves in this city.

“I’m a very religious person, and I think that the person who is a drug mule made a very crazy mistake, but paid with his or her life,” Tobon said. “My feeling is: Why continue to destroy this person’s family when we can do a Christian burial instead?”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.